What It Was Really Like The Day John Wayne Died

Here's a bit of trivia for you: Hollywood star John Wayne almost died twice while filming movies. Of course, those incidents didn't actually kill him; rather, he died on June 11, 1979, at the age of 72. Popularly known as "the Duke," Wayne made a huge name for himself as the heroic leading man in the Westerns and action movies of the day, wielding a certain kind of charisma and bravado that proved absolutely magnetic. But for all that Wayne might have appeared larger than life on the silver screen, he was just as human as his adoring fans. He was diagnosed with lung cancer in September 1964, managing to beat the illness and choosing to be open about it, becoming something of an icon when it came to cancer awareness. But that wasn't the end of that particular chapter, as Wayne was later diagnosed with stomach cancer in 1978, dying a year later.

When it came to the world of Hollywood stardom, Wayne's death was a really big deal, but on that day, there was also a lot more going on in the world. After all, the late 1970s were a time of considerable political unrest and change, for one, both in domestic and international terms. Then, there were also the normal events of the year, which went on ahead despite the death of a movie star. Here's a little look at just what the world was like on the day that John Wayne died.

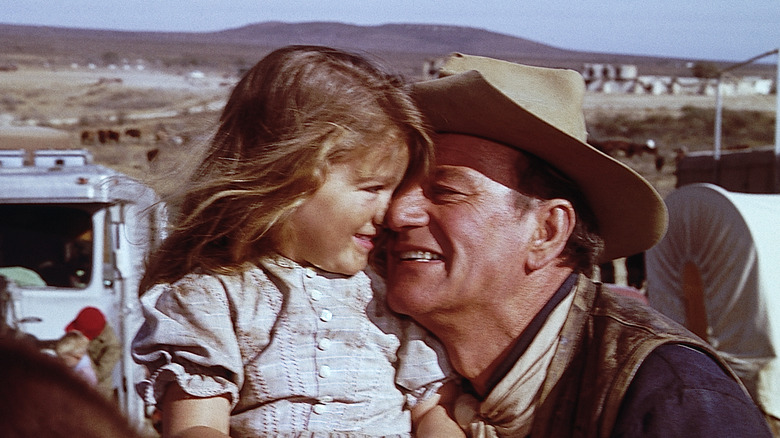

John Wayne died surrounded by his loved ones

John Wayne was nothing short of a Hollywood superstar; that much seems clear, given the outpouring of love expressed at his death. Despite that stardom, though, it was family that mattered most in the end.

After his second cancer diagnosis in 1978, Wayne was eventually hospitalized at the UCLA Medical Center, where words of encouragement flooded in. Literal thousands of letters were sent from around the globe (a notable moment being Queen Elizabeth II herself sending a telegram), President Jimmy Carter stopped by to visit, and Wayne's last public appearance at the Academy Awards saw him met with thunderous applause. That didn't stave off the end, though. Family members said that he was doing poorly in between short bouts of recovery, and he fell into a coma shortly before dying, surrounded by his family.

A spokesperson for the family said that they intended a small service for the larger-than-life actor, and they debated a number of different options — cremation and burial on an island off the coast of California, or a service at his ranch in Arizona. None of those discussions, nor the final decision the family settled on, were made public prior to the service itself, though; ultimately, they settled on a small Catholic funeral, Wayne having actually converted just days before his death. The service was held in the early morning of June 15 at a church in Newport Beach, California, attended only by Wayne's family and closest friends, and he was buried nearby in Pacific View Cemetery.

Cinephiles were being treated rather well

When John Wayne died, Hollywood was putting out some seriously good films. That said, it wasn't anything like the Westerns that had made Wayne a big star. Quite the opposite, really.

By late May 1979, a whole lot of movie buffs were waiting with bated breath for a movie that's since become a sci-fi and horror classic: "Alien." And they really were waiting for a while, given that the preceding year had been full of whispers of a movie about rogue aliens. When the movie finally came out on May 25, people were literally standing in lines around the block just waiting to get into the theater, where they could watch a movie that oozed with style and edge — with a good dose of cinematic horror, of course. Oh, and that's without even mentioning that iconic scene of the titular alien bursting through its victim's chest — a scene that had people literally gasping through mouthfuls of popcorn.

And yes, it's true that "Alien" had been in theaters for a couple of weeks before Wayne died, but even in June alone, it still grossed well over $22 million at the box office, putting it in third for highest-grossing movie of the month. Granted, it lost out to "Rocky II" and "Escape from Alcatraz," which were released on June 15 and 22, respectively — but all in all, it was quite a good month to be a moviegoer.

Drama on Delta Airlines

Anyone who happened to be taking a flight on Delta Airlines on the day that John Wayne died might have been subjected to a rather scary experience: a hijacking. Delta flight 1061 left from John F. Kennedy International Airport at 5:30 p.m., heading off to Fort Lauderdale, Florida. At first, nothing seemed amiss, but after a short while, a man — later identified as Eduardo Guerra Jimenez — knocked on the door to the cockpit. After being mistakenly let inside, he claimed to have a bomb in his bag and demanded to be taken to Havana, Cuba.

The crew complied, and the Cuban authorities were also informed of the hijacking. They sent jets to intercept the plane and escort it to the Havana airport, where it landed without issue and Guerra stepped out, surrendering without a fight and revealing there had been no actual bomb. The crew and passengers were taken back to Miami the next day.

As for Guerra's reasons, well, during the flight, other passengers described Guerra as being rather agitated, perhaps because he was returning to a country where he was considered a traitor. Ten years earlier, he'd actually defected from the Cuban military, flying his fighter jet to Florida in search of political asylum. In that time, however, he'd fallen on hard times, committing petty crimes and finding it impossible to land a good job. Only a year prior, he'd gotten out of prison, and apparently thought his existence meaningless and empty.

The SALT II discussions weren't going well

When it comes to international relations during the 1970s, you can't exactly ignore the tension between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. But the '70s proved to be something of a unique time, and all thanks to something called détente. In general, détente refers to a slight warming in the relationship between the two nations from the late 1960s to the end of the 1970s, including the introduction of arms reduction discussions. The late 1960s were rather promising in that regard, with the strategic arms limitation talks leading to the signing of the SALT 1 treaty in 1972, which limited the number of nuclear missiles and was one of the biggest achievements of the era.

As the 1970s continued, so did those talks, but they ended up just highlighting more problems than solutions. While SALT I had included enough compromise, it did sidestep a couple of issues that the U.S. and U.S.S.R. just couldn't see eye to eye on — namely they involved some specific bits of military technology that the two respective countries refused to limit. And those issues just came to the forefront when SALT II was on the table. On the day of John Wayne's death, those talks were coming to an end, and SALT II was signed on June 17, though it would become something akin to a tragedy for Jimmy Carter and Leonid Brezhnev.

After all, the skepticism surrounding SALT II only became sharper as time went on, with American politicians doubting the Soviets' intentions; ultimately, the treaty was never actually ratified.

People around the world panicked over oil

Nowadays, you've probably heard plenty of people complaining about gas prices at one point or another. But, if you looked back to mid-1979, you'd find that Americans — and plenty of people around the world — had a lot of reason to feel true distress.

The 1970s actually saw two different oil crises — one from 1973 and another that began in 1979 — which cemented the lasting image of long lines of cars waiting at gas stations in the U.S. The 1979 crisis specifically was tied to the advent of the Iranian Revolution, during which Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini coordinated opposition to the shah. Iran's oil production dropped significantly, effectively cutting off global access to crude oil in a way that wasn't easy to deal with. Between the decreased supply and responsive panic buying, the price of crude oil shot upwards from $13 to $34 per barrel between 1979 and 1980.

For the average American, that meant dealing with the federal government's poor solutions to the problem. The Department of Energy ruled that larger refineries should send oil to smaller ones — a choice that ultimately meant there was less gasoline available — and old systems meant that it was impossible to adequately adjust to the given problems. State governments intervened instead, mandating that consumers could only buy a certain amount of gas at a time, a decision that only exacerbated the problem: people had to go to the gas station more often, creating even longer lines.

The political scene in San Francisco was changing

In the history of LGBTQ+ rights in the U.S., among its most major events were the Stonewall Riots, which have an extensive backstory of their own. That said, Stonewall wasn't the only instance of LGBTQ+ communities fighting back against injustice. Over in San Francisco, you have the tragic story of Harvey Milk, a prominent politician well known for being the only openly gay person in public office in California. On November 27, 1978, Milk and Mayor George Moscone were assassinated by a man named Dan White. Fast forward half a year, and White was convicted of voluntary manslaughter (rather than first-degree murder) — a verdict that angered the gay community.

On May 21, 1979, they took to the streets in protest — an event that would become known as the White Night Riots — and what started as a peaceful march to City Hall eventually turned to violence when the police arrived, causing long-standing tensions to boil over. After that, the political scene began to change. There wasn't as much violent backlash as would've been expected, and then-unknown gay (or generally LGBTQ+ friendly) politicians began to gain more traction.

Bearing in mind that elections were on the horizon, well-established politicians also tried to cultivate their image in much the same direction. Mayor Dianne Feinstein actually gained quite a bit of support from the gay community by promising changes and greater diversity, even taking lunch in the Castro District (known for being historically welcoming to LGBTQ+ folks).

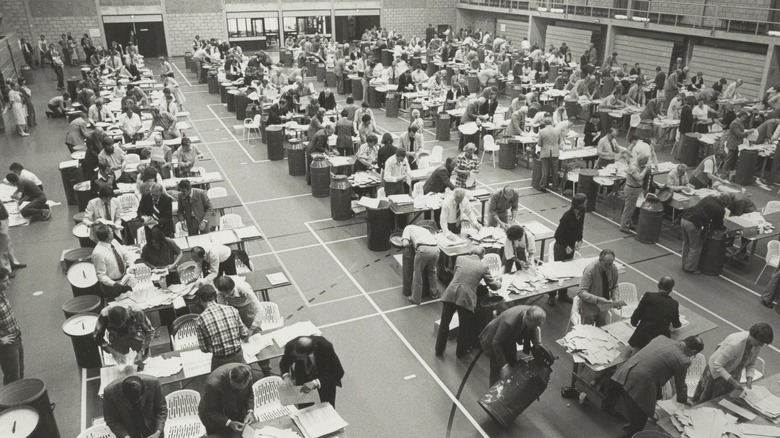

Europeans had a muted response to a historic election

While there might be plenty of lesser-known facts about the European Union, the coalition itself isn't all too mysterious; what may be less familiar to non-Europeans is the European Parliament, the legislative body for the E.U. made up of directly elected officials. Interestingly enough, its first elections had just finished by the time of John Wayne's death in mid-1979. This was history in the making, and a pretty big deal — at least on paper. In practice, the truth was far less glamorous.

The truth is, most Europeans just didn't care in the slightest about the elections; The Guardian called it "the universally designated bore of the year," and one official even commented, "I am loathe to admit it has been a non-event." The numbers support that exact same sentiment, with barely more than half of eligible voters even turning up at the polls.

European politicians certainly weren't helping matters, either. Most political parties put together campaigns out of obligation more than anything, and when they did, they only did so with an eye for how the European Parliament could service their home country, rather than Europe as a whole. The response was somewhat understandable; at best, people were aware that the European Parliament would have little to no real power. Most everyday citizens didn't actually know what the institution was even for, and they didn't really care to learn.

The U.S. economy was on the verge of crisis

Without getting too deep into the nitty gritty of decades of economic policy, up until the 1970s, the federal government was making decisions using decades-old systems. But those old policies started to fall apart for multiple reasons: the exorbitant costs of the Vietnam War, the two different energy crises and oil shortages of the 1970s, and a poor understanding of available data that led to policies which exacerbated problems rather than solving them.

Inflation continued to rise throughout the 1970s — jumping from 1% in 1964 to 14% in 1980 — and by the end of the decade, most Americans believed that inflation was to blame for the worsening economy and flagging businesses. People were expecting the government to take a special interest in driving inflation down, but policymakers struggled to find an acceptable solution.

Drastic times called for drastic measures, and the American public was about to experience something known as the "Volcker Shock." Paul Volcker (pictured above) became chair of the Federal Reserve on August 6, 1979, and he set out to fix the inflation problem, albeit by controversial means. In effect, he forced two separate, major recessions over the course of just a few years, a choice that would cause unemployment to skyrocket to nearly 11% in 1982. He was ultimately successful when it came to inflation — it was down to 3.4% by 1987 — but the public was understandably angry, finding themselves in the midst of the worst unemployment crisis since the Great Depression.

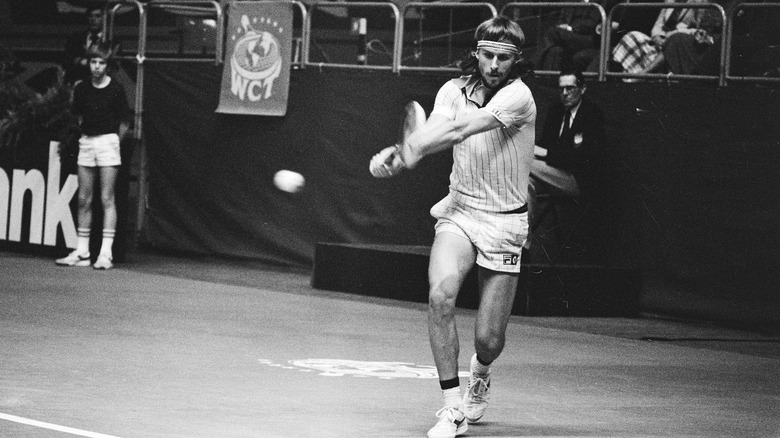

Tennis fans were treated to the end of an exciting tournament

There were some pretty big things going on around the world in mid-1979, whether that be due to world politics or notable deaths. But sports have also been quite the constant, and so fittingly, on the day of John Wayne's death, there was also a bit of competition happening elsewhere in the world. Specifically, that was the French Open tennis tournament, which took place at the Roland Garros Stadium in Paris.

On June 11, thousands of fans packed into the hot, sunny stadium where, on the final day of the tournament, they were treated to something of a surprising match. On one hand, there was the Swedish tennis player Bjorn Borg, who had come into the competition as one of the top-seeded players and proved himself worthy of that distinction, dominating in earlier matches of the tournament. But on the other hand, there was relative newcomer Victor Pecci, the only professional tennis player from his native country of Paraguay.

Pecci had spent fairly little time in major, publicized tournaments, mostly just racking up achievements in smaller and lesser-known competitions. But upon arriving in Paris, he was at the center of upset after upset, and he quickly became the fan favorite. He managed to work his way into the finals, playing with determination and poise in equal measure, and even though Borg pulled out the win, Pecci — and those around him — had nothing but hope for his future.

The Middle East was about to change forever

If you turned your eye away from the U.S. and Europe in 1979, you would find another part of the world in a very notable state of flux: the Middle East. And while there wasn't a specific event that took place on June 11, that date does sit in a period of time that changed the region forever.

For the most part, that story starts with the Iranian Revolution. The U.S.-backed shah had become widely unpopular in recent years due to a combination of a weakened economy and repressive policies. People began turning to the teachings of religious leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, who became the leader of the country after the deposition of the monarchy in February of that year. But that single event would ultimately cause a domino effect across not only political borders, but across time itself. For one, the establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran actually led Saddam Hussein to become the president of neighboring Iraq in July, as he saw Khomeini as a potential threat — an assessment that eventually led to multiple wars over the next few decades.

Not only that, but Khomeini also helped push new ideologies to a very responsive public: political Islam, for example — a concept that became its own form of protest and ultimately spawned groups like the Taliban. On top of that, he also fostered an anti-Western sentiment that quickly grew, one which truly came to light with the Iran Hostage Crisis later that same year.