The Messed-Up History Of The Panama Canal

Spanning roughly 50 miles, the Panama Canal links the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Dubbed one of the seven wonders of the modern world, per History, the canal generates billions of dollars in tolls from the approximately 13,000 to 14,000 ships that pass through annually. Different nations entertained the notion of such a passage since the 1500s, but the canal seemed like an impossible dream. As an American dream, it would become a reality.

Spurred on by Rough Rider in chief Theodore Roosevelt, the U.S. began work on the canal in 1904 and finished the job in 1914. On the surface it all sounds so simple: a man, a plan, a canal, Panama! But unlike that classic palindrome, the history of the Panama Canal isn't as straightforward when you look back on it. It was a story of horrific hardships, dictatorships, cartels, secret deals, and double-dealing. Despite being an engineering dream come true, the Panama Canal is mired in nightmares.

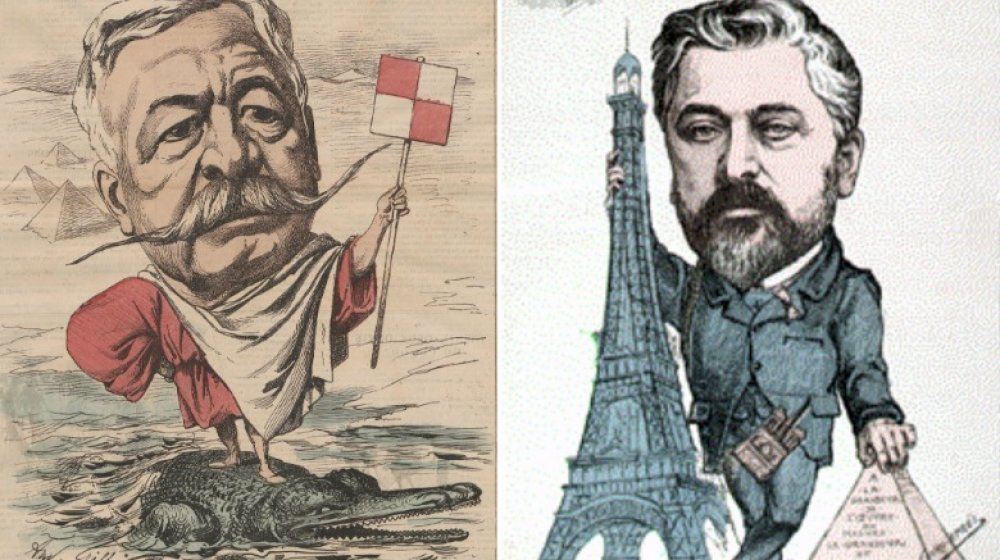

France's disastrous bid to build the Panama Canal

In the 1880s, France had compelling reasons to believe it could carve a canal through Panama. As History detailed, the project was led by Ferdinand de Lesseps, who oversaw the construction of the Suez Canal connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Indian Ocean. De Lesseps later hired Gustave Eiffel, the mind behind the Eiffel Tower, the Statue of Liberty's metallic skeleton, and other stunning structures. More than 100,000 investors backed the planned canal amid a wave of "patriotic fervor," per PBS. With an estimated duration of 12 years and a projected total cost of $132 million, construction started in 1881. Nearly eight years later, only 11 miles of canal had been completed and costs exceeded $280 million.

Canal workers paid the ultimate price. Men dropped like flies as mosquitoes carrying malaria and yellow fever turned France's massive undertaking into a mass grave. A staggering 75 percent of employees hospitalized in Ancon, Panama died. Along with disease, "hellish heat," snakes, heavy rain, and the treacherous Chagres River wreaked havoc. Workers trudged chest-deep in mud, only to see their progress undone by lethal mudslides that buried men and machines. At least 20,000 people died overall. De Lesseps' business went belly-up, and investors were up in arms. De Lesseps, Gustave Eiffel, and multiple executives were prosecuted and convicted of fraud and mismanagement. But they managed to have their sentences overturned.

The U.S. played dirty in Panama

France spent most of the 1880s trying to dig the Panama Canal but dug a giant hole for itself instead. Teddy Roosevelt saw the whole thing as a golden opportunity for the U.S. to step in. As president, Roosevelt urged Congress to strike while the iron was hot, declaring in his 1902 State of the Union Address that it was "emphatically" in the United States' interest "to begin and complete [Panama Canal construction] as soon as possible." That year, Uncle Sam struck a deal to acquire France's equipment and property rights for $40 million or less, according to PBS.

Colombia-controlled Panama seemed reluctant to reach an agreement. So in 1903, the United States staged a Panamanian uprising, even drafting a constitution for Panama beforehand. History reported that America cut off train service to stop Colombian troops from quelling the rebellion and sent a warship to deter them from fighting. Bullets were met with economic firepower as the United States paid Colombian soldiers $50 to disarm. The entire conflict ended within hours.

That manufactured uprising foreshadowed a significant shift in U.S. foreign policy. In 1904, Uncle Sam began building the Panama Canal and President Roosevelt announced the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine. The corollary essentially said the United States gave itself permission to intervene militarily in the affairs of other countries in the Western Hemisphere.

Panama Canal construction was stained by segregation, exploitation, and explosions

The Panama Canal was largely built on the backs of Caribbean workers, per the University of Kansas Medical Center. They poured in from Barbados, Jamaica, Martinique, and St. Martin, enticed by "the promise of better wages and free medical care." Unfortunately, the U.S. was awful at keeping its promises.

The Isthmian Canal Commission assigned U.S. citizens to the so-called gold payroll, meaning Americans would occupy administrative and foreman roles and got paid in gold. Skilled Europeans and unskilled laborers from Panama and the Caribbean got lumped together on the silver payroll. Silver-roll workers were paid in Colombian pesos, lived in "crowded housing," and had bad food. Hospitals were racially segregated, and facilities for nonwhite workers had a mortality rate 10 times higher than that of whites-only hospitals. That disparity was echoed in the official canal death toll. Out of 5,609 total fatalities, only 350 were white, according to the Guardian.

The canal's true death toll is likely much higher. The Conversation explained, that for years workers had virtually no legal protections because administrators banked on workers being so desperate that they would mostly accept the horrific conditions. As the Linda Hall Library described, laborers faced landslides, swinging cranes, and train accidents. Dynamite was ignited by lightning, steam shovels, and "blasts of hot air" caused by chemical reactions. One worker recalled seeing "trainloads of dead men being carted away daily" like "lumber."

Panamanian citizens became second-class citizens in the Panama Canal Zone

Per the BBC, in 1903, the United States established the Panama Canal Zone to serve as "a home away from home for the Americans" tasked with canal construction and maintenance as well as the workers supporting them. Known as Zonians, these mostly white Americans "lived a life of luxury in secluded tropical communities" while black Panamanian and Caribbean inhabitants led much harsher lives. The LA Times reported that Zonians had their own movie theatres, medical facilities, post office, police, and courts. They even had a special brand of matchsticks that Panamanian and Caribbean residents couldn't buy.

Housing and schools were racially segregated. The U.S. Supreme Court created a wrinkle in that arrangement by deeming school segregation unconstitutional in 1954. Even then, segregation didn't end until the 1970s. And as the Anacostia Community Museum described, when the Zonians did integrate schools and housing, they did the bare minimum. They applied the court's ruling almost exclusively to U.S. citizens, forcing black Panamanians and Caribbean natives to attend different schools and live in different lodgings. Panamanians not only had to tolerate racial discrimination by Americans, but they also got hassled by American police. Unsurprisingly, they deeply resented the Zonians.

Tensions in the Panama Canal Zone exploded into deadly riots

Although Uncle Sam helped Panama declare independence from Colombia, Panama often found itself under Uncle Sam's thumb. According to the U.S. National Archives, soon after Panama signed the 1903 Hay-Bunau-Varilla treaty which greenlit canal construction, disagreements arose over how to interpret certain terms. Over the years, the countries would butt heads over Panamanian sovereignty, permission to fly the Panamanian flag in the Canal Zone, the exclusion of Panamanian goods from the Canal Zone, and institutionalized discrimination against Panamanian citizens by the United States.

By 1959, relations between the nations had grown so acrimonious that riots erupted in Panama. President Eisenhower attempted to smooth things over by introducing a program that promised fairer pay and housing for Panamanians, who, as PRI described, had been habitually denied jobs in the Canal Zone and lived under what one resident described as "an apartheid" system. However, Eisenhower's promise rang hollow until 1964, when tensions reached a deadly crescendo.

In 1964, Panamanian students tried to fly their country's banner next to the American flag at an American high school. Canal Zone police halted them, and "about 2,000 hostile Americans surrounded [the Panamanians], singing 'The Star-Spangled Banner.'" The two sides tussled, tearing the Panamanian flag. Later that day, Panamanian students unleashed their pent-up rage, throwing bricks, rocks, and Molotov cocktails. U.S. troops were sent to squelch the rioting, leading the deaths of 22 students and four soldiers.

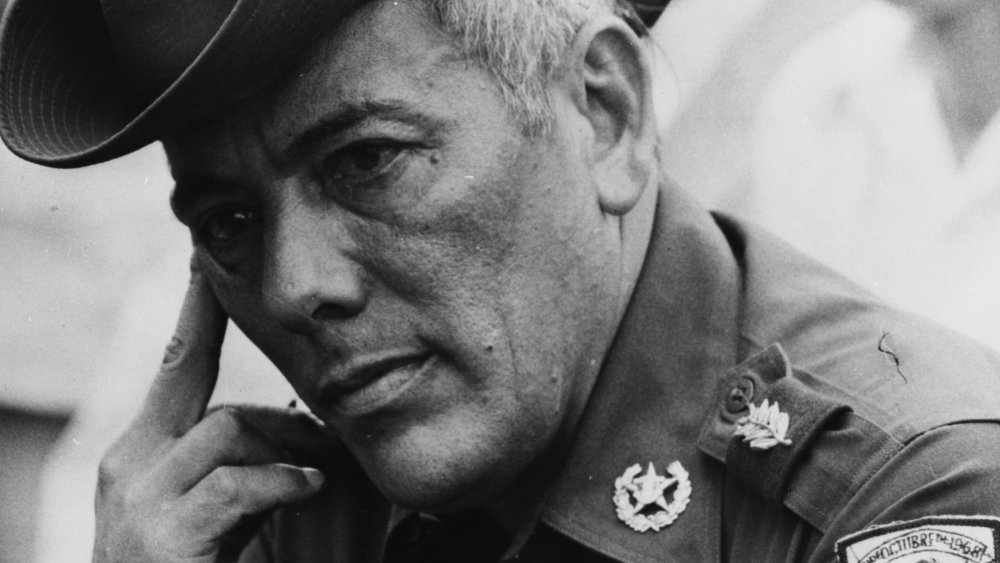

The reign of Panamanian strongman Omar Torrijos Herrera

In 1964, longstanding animus over the United States' control of the Panama Canal and mistreatment of Panamanian people ignited into fiery riots in which 22 Panamanian students and four U.S. soldiers were killed. According to PRI, the riots "directly led to an agreement" for the U.S. to cede control of the Canal Zone to Panama on New Year's Eve 1999. The countries achieved that agreement in 1977 during the regime of Brigadier General Omar Torrijos, who used his pursuit of the Panama Canal as a weapon against his own citizens.

An officer in the Panamanian National Guard, per Britannica, Torrijos took part in a 1968 coup that established a military dictatorship. Boasting the official title, Chief of Government and Supreme Leader of the Panamanian Revolution, Torrijos would usher in an era of torture, arbitrary arrests, corruption, and outright murder. As the Conversation explained, the military junta he helped establish is suspected of more than 100 murders and disappearances.

Torrijos portrayed all criticism of him as a "[betrayal of] Panama over the canal," per the New York Times. When students rioted over food prices, he basically called it a hoax perpetrated by "U.S. intelligence agencies and Americans living in the Canal Zone." He justified deporting political opponents by accusing them of being in league with U.S. politicians.

Panama Canal negotiations were jeopardized by the murder of a priest

As recounted in The History of Central America, Panamanian strongman Omar Torrijos "used on-duty soldiers to terrorize political opponents." When a group of female activists published a protest newsletter that decried Torrijo's ruthless suppression of critics, he sicced his National Guardsman on them. The guardsmen raped many of the women and intimidated them with guns. Some of the activists saw their cars confiscated. Torrijos also used the U.S. military's helicopters, which were on loan, to rain death on activists in the mountains of Panama. A helicopter also featured prominently in the 1971 abduction and murder of Father Hector Gallego.

The New York Times said the incident "sent shock waves through Latin America and may even threaten the continued control of the Panama Canal by the United States." Gallego, described by author Thomas Pearcy as "a vocal critic of Torrijos," had enemies in high places. According to his fellow clergymen, he infuriated landowners in the parish of Santiago de Veraguas by trying to improve peasants' lives. The Buffalo News reported that "Gallego was widely rumored to have been interrogated, beaten and thrown to his death from a helicopter over the sea" by Panamanian soldiers. Torrijos forbade news outlets from covering Gallego's disappearance and gave them something else to talk about: anti-American demonstrations in the Panama Canal Zone, which U.S. officials believed served as a distraction.

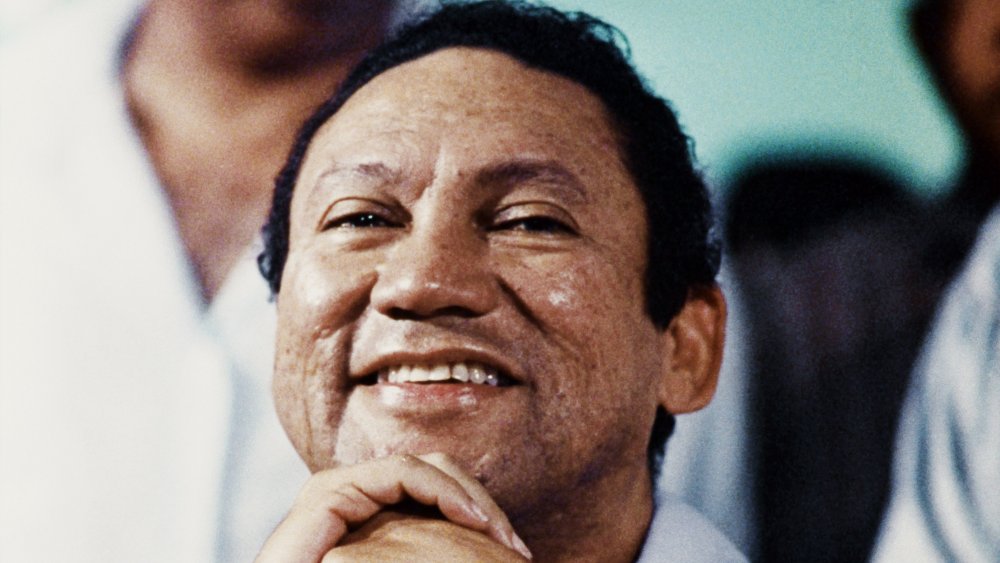

The rise of 'Pineapple Face' Manuel Noriega

Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega, a.k.a. "Pineapple Face," was born "less than a mile from the U.S.-controlled Panama Canal Zone," according to Reuters. His face was pocked with acne scars, and his brain was filled with vicious ambition. When Omar Torrijos seized power in 1968, he named Noriega as the head of military intelligence. Noriega handled illicit army deals and "ran its ruthless secret police force." As NBC described, while in the Panama National Guard he caught the eye of the CIA, which turned a blind eye to his corruption and hired Noriega as an informant.

Torrijos referred to Noriega as "mi gangster" and turned to him when wanted to make someone disappear. After Torrijos died in a 1981 plane crash, his gangster ruled Panama, ascending to the country's top spot in 1983. Noriega continued to work for the CIA, aiding their operations in other Latin American countries. He also continued to be a gangster, engaging in rampant money-laundering, having a critic decapitated, and helping cocaine kingpin Pablo Escobar smuggle drugs into the U.S. Noriega got away with a lot because he was such a valuable CIA asset and, as ABC explained, the U.S. had a vested interest in protecting the Panama Canal Zone. So Uncle Sam was none too happy when Noriega deposed a Panamanian president whose election "had been a precondition for the United States to hand back control of the Panama Canal."

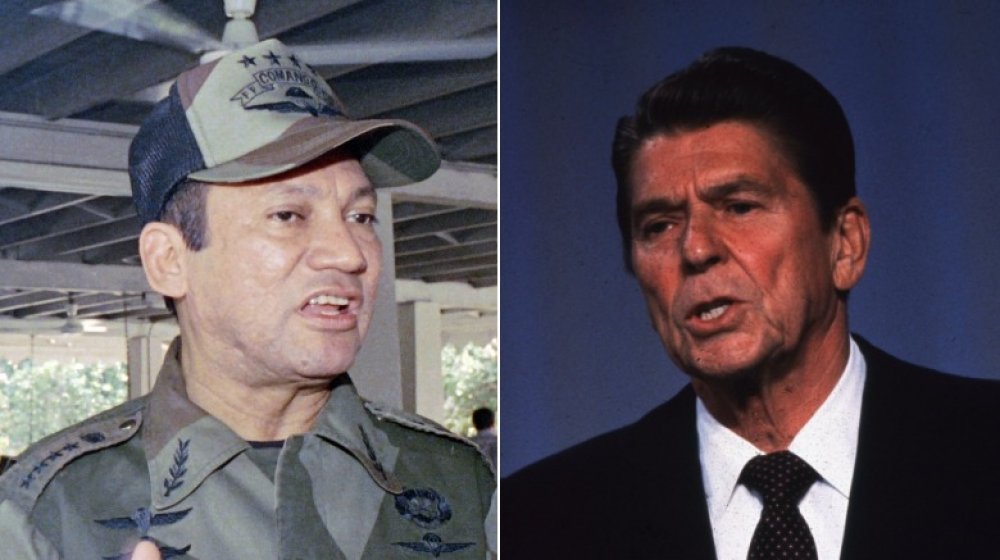

Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega's connection to Iran-Contra

When President Ronald Reagan urged America to "just say no" to drugs, that should have also meant saying no to Panama's military dictator, Manuel Noriega. According to History, in 1983, a Senate committee determined that Panama had become a hub of drug smuggling. (Even in 2019, the Panama Canal is used to transport tons of cocaine). Yet Noriega still received Reagan's stamp of approval. The Gipper didn't turn on him until 1986.

Why did it take so long to condemn Noriega? As ABC detailed, the military dictator aided Reagan in his war on Communism and America needed Noriega to protect the Panama Canal Zone, which the U.S. still viewed as one of its territories. The situation became even more complicated during Iran-Contra, when the Reagan administration illegally sold weapons to Iran in order to fund paramilitary operations in Nicaragua. Reagan wanted to topple Nicaragua's Marxist government, and Noriega offered to help.

Noriega played both sides. At times he aided Nicaragua and during Iran-Contra he volunteered to assassinate Nicaragua's leader and allow the U.S. to use Panama as a base of operations. His assistance apparently outweighed the kilos of cocaine he was transporting. The U.S. also ignored narcotics trafficking by the Contras. Plans to collaborate with Noriega fell apart after Iran-Contra got exposed. Even worse, shortly before that bombshell dropped, the public discovered Noriega had aided both the CIA and Nicaragua's government.

The shots heard round the Panama Canal Zone

By 1989, Manuel Noriega's days as a Panama's dictator were numbered. Per the Washington Post, in October, Noriega's top counterintelligence official, the US-trained Captain Nicasio Lorenzo, tried to overthrow him. By December, Noriega was one jittery dictator. A member of the U.S. military told the Washington Post that Noriega feared another coup attempt would occur on December 15. He was wrong; the U.S. invaded Panama on December 20.

The circumstances surrounding the invasion are shrouded in controversy. On the night of December 16, four Marines in civilian garb rode past Noriega's military headquarters in the Canal Zone. According to one version of events, the men were headed to a restaurant but took "a wrong turn." Things turned deadly at a checkpoint, where members of the Panamanian Defense Forces tried to physically remove the Marines from their vehicle. The driver tried to pull off and the armed Panamanians pulled the trigger, killing Marine officer Robert Paz. Afterward, two American witnesses were detained, interrogated, and beaten.

A number of U.S. service members and civilians have disputed this account. As the LA Times detailed, they alleged that "a small group of U.S. troops who called themselves 'the Hard Chargers'" intentionally initiated the conflict to create a pretext for the invasion. They further asserted that the Hard Chargers had a pattern of trying to provoke Panamanian soldiers. Interestingly, less than 48 hours after Paz was shot, UPI reported that a U.S. soldier shot a Panamanian guard.

Did 'Operation Just Cause' have a just cause?

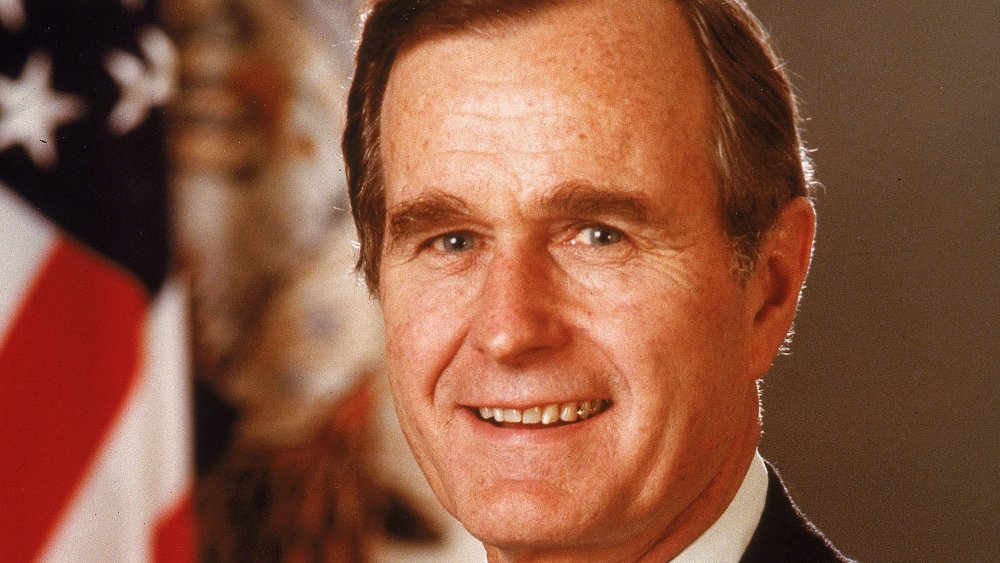

Ordered by President George H.W. Bush on December 20, 1989, the U.S. invasion of Panama was called Operation Just Cause. Evidently, Bush really wanted to emphasize that he had a compelling reason to overthrow Panama's government. In fact, he had four reasons. As outlined by Politico, Bush believed military dictator Manuel Noriega posed a danger to the roughly 35,000 Americans residing in Panama. Secondly, he wanted to uphold democracy by taking down a despot. Thirdly, Noriega trafficked drugs, and lastly, eliminating Noriega would protect the 1977 treaties that guaranteed the U.S. would hand full control of the Panama Canal Zone to Panama on December 31, 1999.

Newsweek contributor Peter Eisner wrote, "American civilian and military officials told me there was no justification for the invasion," let alone a "just cause." Eisner argued that none of the charges leveled against Noriega had been proven. However, that claim should come with an asterisk. After all, as NBC noted Noriega headed a brutal military junta that beheaded one of his critics. He engaged in money laundering and for a long time seemed to be involved in drug trafficking. However, America had tolerated and cooperated with Panamanian despots up to that point. And Ronald Reagan ignored Noriega's alleged drug trafficking for years, per History. Just or not, the operation caused a lot of bloodshed. The Pentagon estimated that 516 Panamanians died during the invasion. An internal memo placed placed the death toll at 1,000.

North Korea attempted to smuggle weapons through the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal has long been used to smuggle booger sugar. In fact, according to the Maritime Herald, in 2018, law enforcement confiscated 73 tons of cocaine. But in 2013, Panamanian authorities encountered a different illicit sugar on a North Korean ship. As the BBC detailed, stashed under sacks of sugar were 240 tons of Soviet-era weapons from Cuba, which North Korean officers sought to sneak through the canal. This decidedly unsnortable paraphernalia included fighter jets, air defense systems, command and control vehicles, and missiles.

While these items are dinosaurs compared to weapons of modern warfare, North Korea violated sanctions imposed by the United Nations which bar the Hermit Kingdom from importing anything but small weapons and forbids exporting weapons altogether.

Per World Maritime News, a Panamanian court sentenced the ship's captain and first mate to 12 years in prison. The UN placed sanctions on the ship's operator, Ocean Maritime Management. Hilariously, the company essentially tried to smuggle its own ships through the canal, altering the names of 13 out of its 14 vessels in an attempt to circumvent the sanctions.