The Truth About The U.S. Government Poisoning Booze During Prohibition

In 1919, the 66th United States Congress got busy laying down the Volstead Act, and prohibition became, as they say, "a thing." The text stated that "No person shall on or after the date when the eighteenth amendment to the Constitution of the United States goes into effect, manufacture, sell, barter, transport, import, export, deliver, furnish or possess any intoxicating liquor except as authorized in this Act, and all the provisions of this Act shall be liberally construed to the end that the use of intoxicating liquor as a beverage may be prevented."

Translation: The creation and distribution of hooch stronger than .5% was now, officially, crossing the line. And so it was that the American public were rendered sober as a priest.

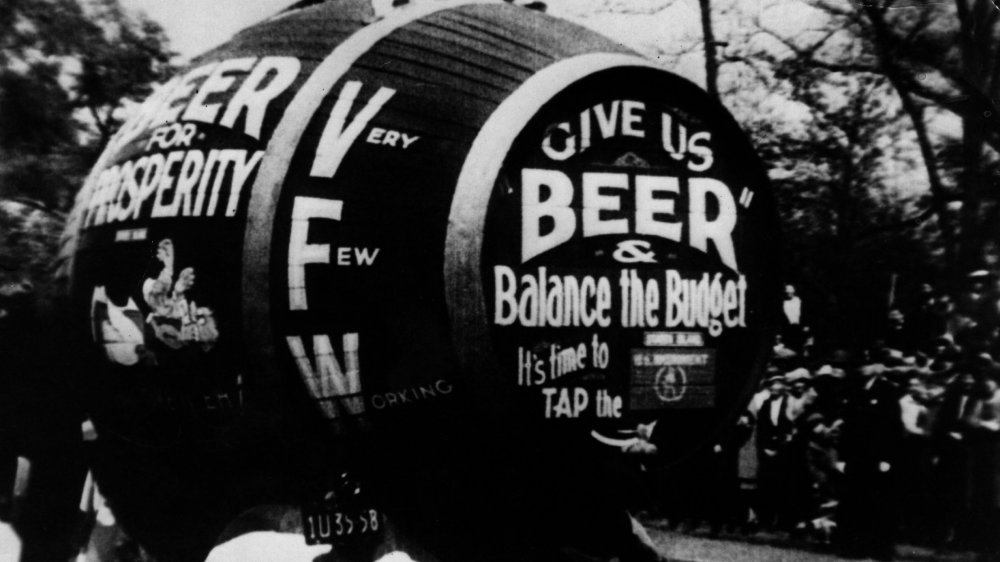

For anyone who's never met a priest, this means "they were still hammered, they just tried to stay quiet about it." Bootlegging became America's new favorite pastime, with speakeasies turning into the backbone of disreputable organizations, involving figures like Al Capone. The government, not thrilled about the population's apparent unwillingness to live a life free of awesome Friday nights, then took drastic actions that a lot of people have forgotten about — they decided to poison their citizens.

Booze and jeers

One of the chief sources of down-low drink was industrial alcohol, high-test rotgut used in manufacturing, which was unsuitable for human consumption. Criminals, not being ones to let little things like the potential for blindness and death get in their way, took to "renaturing" the product, chemically removing the parts that made it toxic and selling it to the general public. Authorities weren't having it, and they ordered manufacturers to add significantly more poisonous ingredients to their products.

How poisonous? According to Slate, the list of additives included — but was not limited to — "gasoline, benzene, cadmium, iodine, zinc, mercury salts, nicotine, ether, formaldehyde, chloroform, camphor, carbolic acid, quinine, and acetone." However, following in the steps of Boromir, Americans just kept taking shots, even if it wasn't in their best interest. By late 1926, a rash of poisonings cropped up, with victims experiencing gruesome hallucinations, violent illness, and death. In the three days after Christmas 1926, 23 people in New York City died from government-toxified rotgut. At least 700 died over the next two years, and those were just the ones on record. As New York City medical examiner Charles Norris pointed out, the measures disproportionately affected the poor, as they were the ones unable to access higher-quality booze.

In the end, there was a small public outcry, but the program wasn't put to death, really, so much as it withered on the vine. By the time that prohibition was called off in December of 1933, the whole thing became another one of those quirky US government bygones that everyone put in the backs of their minds, like MKULTRA, or that time they accidentally dropped a nuclear weapon on North Carolina.