The Messed Up Truth About The Louisiana Purchase

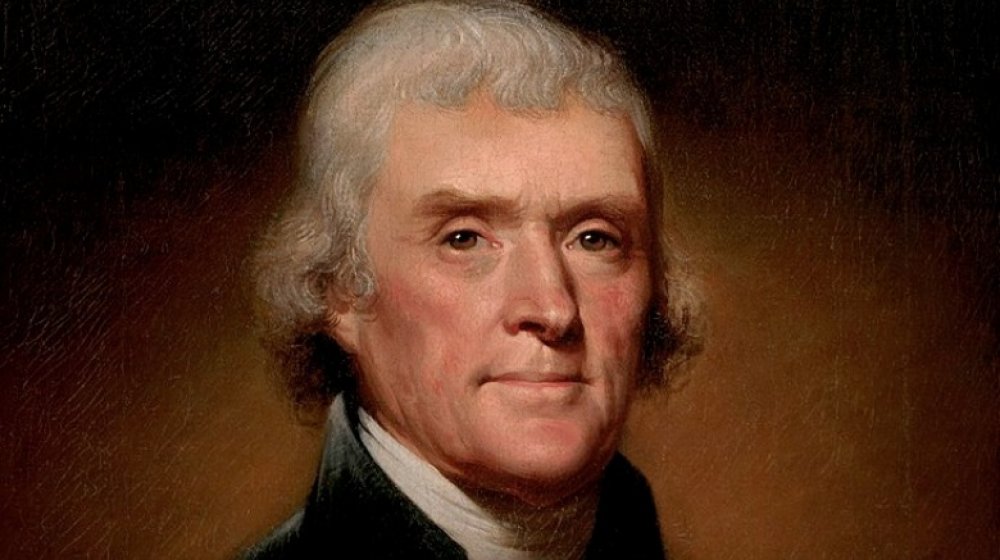

The Louisiana Purchase is usually presented as an incredible, inspiring moment in American history in which President Thomas Jefferson, wise, benevolent eyes twinkling under his powdery white wig, made an incredibly shrewd real estate deal with notorious, disgraced French emperor Napoleon Bonaparte and, with one stroke of his giant quill pen, doubled the size of the United States of America for the bargain price of $15 million, or just three cents an acre. What we don't usually learn about is the negative domino effect this treaty had in terms of inspiring the concept of manifest destiny or the belief that white colonists had a God-given duty to expand across North America and redeem and remake the land in their own image.

The Louisiana Purchase not only doubled the size of the United States, but it rapidly expanded and weaponized the government's persecution of Native Americans over their right to keep the land they'd lived on for centuries. With the expansion of the country came the expansion of slavery, further inflicting more pain and loss in the name of American growth. Like much of American history, the story is much darker and more complicated than the typical heartwarming fables many of us were made to memorize and recite back on our Social Studies tests.

Robert La Salle claims La Louisiane for France

As noted by the World Digital Library, what would become the Louisiana Territory came under French colonial rule in 1682, when explorer and fur trader René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, who had already made a name for himself as a farmer and landlord in Canada, founding Fort Niagara near Youngstown, New York, and exploring the Great Lakes region, led an expedition down the Mississippi to the Gulf of Mexico. He claimed the region for France and named it La Louisiane after King Louis XIV.

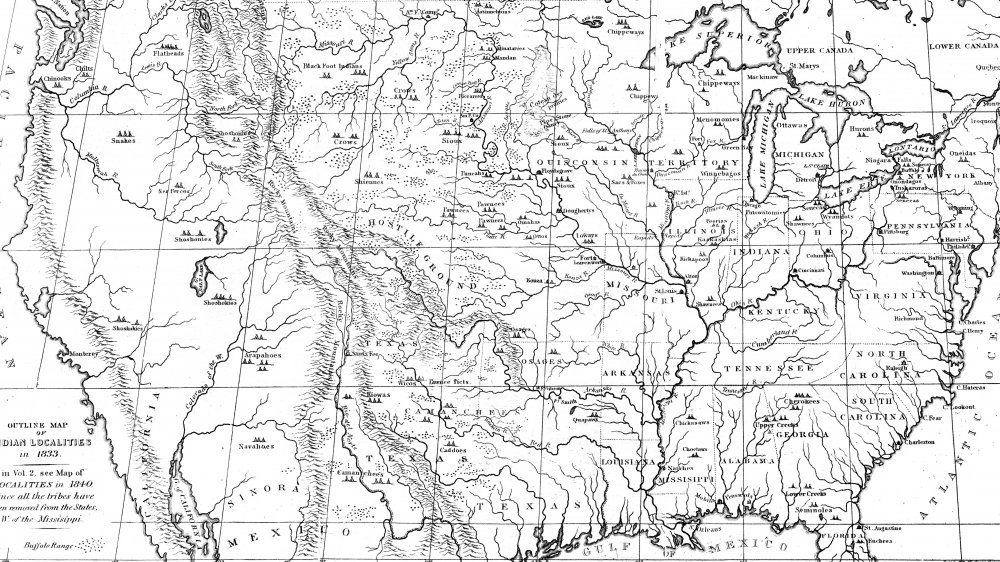

The territory covered, wholly or partially, what would eventually be 15 American states, including the entirety of Arkansas, Missouri, Iowa, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Nebraska and portions of Louisiana, Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota, Texas, New Mexico, Montana, Wyoming, and Colorado, as well as parts of the Canadian provinces of Saskatchewan and Alberta. Colonization began in 1699, and King Louis XIV ordered the establishment of a settlement at the mouth of the Mississippi to guard against possible British infiltration.

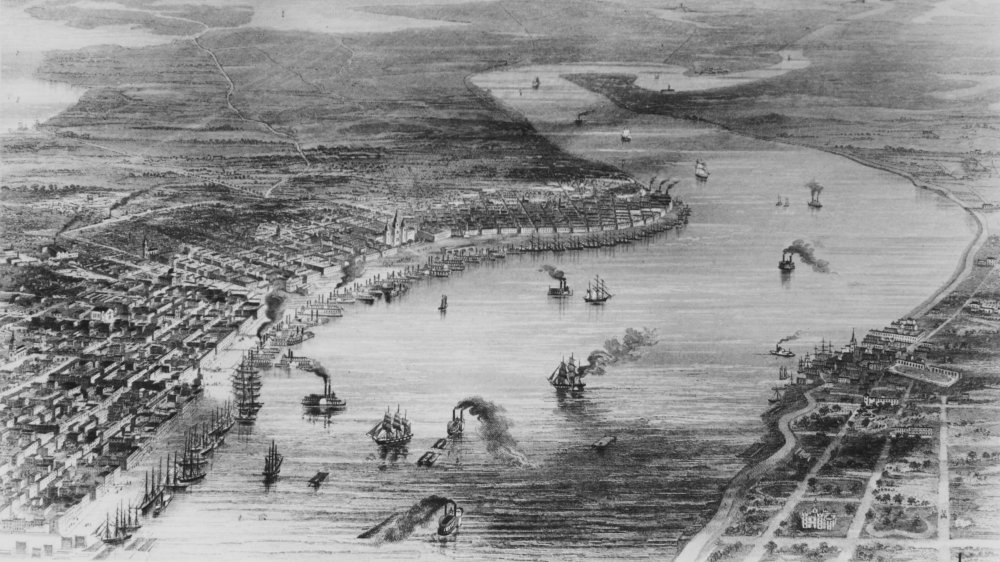

The city of New Orleans

In 1718, Jean-Baptiste le Moyne founded the settlement of New Orleans. According to Smithsonian Magazine, "By the time of the Louisiana Purchase, its population of whites, slaves of African origin and 'free persons of color' was about 8,000," and the city's economy was booming due to farming exports. New Orleans became the capital of the region in 1723.

The Louisiana Territory changed ownership among European colonizers several times over the next century. The region included French, Spanish, Acadian, and German settlements, along with those of Native Americans and American-born settlers living in the frontier. King Louis XV of France was that convinced the area was worthless and gifted it to his cousin, Charles III of Spain, in 1763. It went back to France in 1800 via a secret treaty between Napoleon Bonaparte and Spain's Charles V in a land deal that returned a small Italian country, then owned by France, to Spain in exchange for the Louisiana Territory.

A threat to the American economy

As stated in Smithsonian Magazine, the return of the Louisiana Territory to France scared President Thomas Jefferson because he assumed Napoleon was threatening the United States' access to its Western settlements and the Gulf of Mexico, which were vital to the American trade industry. Jefferson was a bit of a Francophile and had spent five years living in France as the American minister to Paris, but he feared that if the deal went through, "it would be impossible that France and the United States can continue long as friends."

Furthermore, Juan Ventura Morales, the Spanish administrator watching over the territory before its official transfer to France, ended American access to New Orleans' warehouses, endangering stored goods waiting to be shipped elsewhere. New Orleans had to remain open to the United States in order to keep the American economy intact. In particular peril was the fur trade, which made up a large part of the western territories' economy — fur traders subsequently threatened to take New Orleans by force in order to continue doing business at its port.

Surprise! The Louisiana Territory is yours, Thomas Jefferson!

Smithsonian Magazine states that in January 1803, Jefferson sent former congressperson and governor of Virginia James Monroe to France with discretionary powers and funds to buy New Orleans and part of Florida from Napoleon. However, by the time Monroe reached France in April, Napoleon had already decided to sell the Louisiana Territory to the United States. His armies, which would have come from the colony of Saint Domingue (now Haiti) to occupy New Orleans had been defeated in the Haitian Revolution, during which enslaved Haitians revolted and won a successful insurrection against the French colonizers. Between the revolution and yellow fever, explains National Geographic, Napoleon didn't have enough troops to send to the Louisiana Territory, nor did he have access to Haiti's sugar, coffee, cotton, indigo, and other crops, which he had planned on processing in the territory. He needed money, and he had a willing, if slightly hapless, buyer suddenly appear before him.

The United States purchased the entire Louisiana Territory for $15 million, which immediately nearly doubled the size of the country at the cost of about three cents per acre. This sudden acquisition opportunity was a surprise to Jefferson and his cabinet, who had really only wanted to buy New Orleans and part of Florida when entering negotiations. In fact, as discussed by History.com, the boundaries of the territory weren't even officially settled until 1818 and 1819.

Manifest destiny: not really so divine

According to TeachingHistory.org, the term "manifest destiny" wasn't coined until 1845, when journalist John O'Sullivan called the United States annexing Texas "the fulfillment of our manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions." However, one could argue that it was the Louisiana Purchase that set the stage for viewing western expansion as a divine impetus. CNS News quoted Dr. Jim Sofka on the Louisiana Purchase: "If you bought Manifest Destiny, it seemed to work just because of the enormous acreage involved and it seemed to give validation to that idea that the United States ought to control the continent."

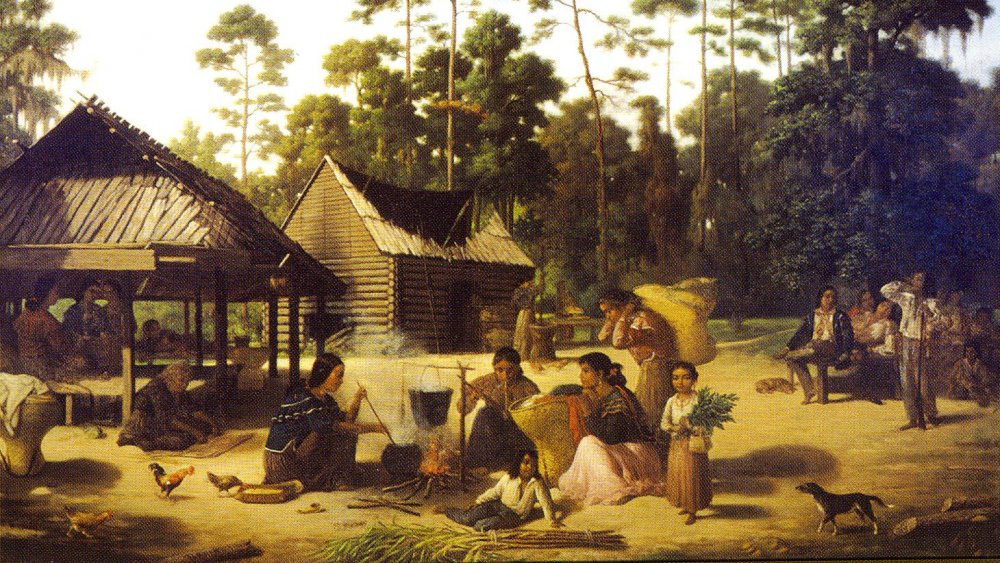

In 1872, artist John Gast depicted manifest destiny as an angelic white woman literally bringing light across the land as she leads settlers into the West, "clearing native peoples and animals, seen being pushed into the darkness." Even Schoolhouse Rock, beloved educational cartoon of the '70s, got into the act, merrily depicting the Louisiana Purchase as the result of colonists' need for "elbow room" on the crowded East Coast. "Elbow Room" contains the lyrics "it's the west or bust/in God we trust" and includes a scene in which an arrow zanily pierces a colonist's hat as the singer explains "there were plenty of fights/to win our rights." This creepily hints at the unfortunate truth as explained by the Smithsonian American Art Museum: "The self-serving concept of manifest destiny [...] was used to rationalize the removal of American Indians from their native homelands."

The Louisiana Purchase wasn't such a bargain after all

The standard discussion of the Louisiana Purchase revolves around what historian Robert Lee described to Slate as its "celebrated reputation as one of the greatest real estate bargains in history." Indeed, historians quoted in CNS News discuss not only the familiar "three cents an acre" figure but refer to the deal as a boost to France's economy: "The motive was, 'hey we're broke with not a penny in the treasury. There are no taxes being collected. Nothing. Let's do something.' So, they did it. [...] The money [Napoleon] got from the Louisiana Purchase enabled him to finance a better government ... it was a damn good idea at the time."

There is no mention here of Napoleon's armies' decimation due to the victorious uprising of enslaved people that resulted in his loss of access to Haitian raw materials earmaked for processing in the Territory, which surely had quite a bit to do with his eagerness to sell. Furthermore, Robert Lee also points out that the ultimate cost to the United States government has gone far beyond the original $15 million. In 2017, Lee used a geodatabase to map the amount of money spent to acquire Native Americans' titles to the land within the Louisiana Territory between 1804 and 2012 and calculated the total as $2.6 billion — or over $8.5 billion when adjusted for inflation.

The United States goverment's "breathtakingly stingy offers"

Robert Lee's 2017 examination of the true dollar amount paid out by the United States government to Native American tribes in order to obtain the rights to the land within the Louisiana Purchase was the first of its kind since the 1940s. Government lawyer Felix S. Cohen published an article in 1946 that estimated a dollar amount of $300 million, which was, according to Lee in a Slate article discussing his study, "erroneously cited as gospel ever since." Cohen also claimed that "the Indians did not get such a bad deal, considering the values of land at the time the various cessions were made. At least, the Indians got more for the Louisiana Purchase than Napoleon did."

In merely considering the amount of money paid out to tribes, Cohen ignored the low prices paid to them for their land and the fact that Native Americans started suing the United States government concerning broken and unfair treaties, usually receiving terrible awards that excluded interest and value that wasn't represented by markets. According to Lee, the Louisiana Purchase "was not a bargain because of how little the United States paid France; it was cheap because of how little it paid Indians."

Pre-emption: The real and destructive "bargain"

Perhaps even more destructive than the historical underpayment of fees to Native American tribes for their land was the right of "pre-emption" that came with the Louisiana Purchase to, as Lee explains it, "expand political authority into Indian country without the interference of other would-be colonizers." In other words, the United States could do what it pleased with its new territory, be it negotiating purchases of land from Native Americans or driving them off by force. Neither France nor any other European country would intervene.

Upon signing the agreement with France, the United States took over the existing system of treaties between France and Native American tribes. The U.S. government was fine with making treaties with the Native Americans — but those treaties were now backed by "looming threats of violence." The true so-called bargain of the Louisiana Purchase wasn't the $15 million paid to Napoleon, nor was it even the additional $2.6 billion paid out over the years to Native American tribes. It was the "right" to essentially undercharge for and/or outright steal land from these tribes.

Native Americans sue the United States

Thanks to "pre-emption" and the unfair methods the United States government was now officially using to "negotiate" with Native Americans, the Louisiana Purchase kicked off the formal process of questioning Native American sovereignty and removing many tribes from their lands. 64 Parishes reminds us that this is generally attributed to Andrew Jackson and his forced relocation of the Cherokee Nation, but it started here, and therefore the "era of removal" took place between 1803 and 1840.

The French and Spanish governments had established and codified their own rules for dealing with Native Americans, and in negotiating the Louisiana Purchase, France did insist that the U.S. recognize and honor the Spanish regulations and treaties already in place. These practices did continue until the 1820s, but as mentioned above, the Louisiana Purchase signified the beginning of the end of these treaties. 64 Parishes details the experience of the Caddo tribe of Louisiana, who served as peacekeepers in the then-undefined boundary between Spanish Texas and American Louisiana. Once the United States annexed Texas and the Spanish withdrew from the area, the Caddos' position was no longer recognized, and in subsequent treaties, the Caddo tribe lost almost one million acres of land to the United States and were eventually forced to migrate to Oklahoma.

Was the Louisiana Purchase unconstitutional?

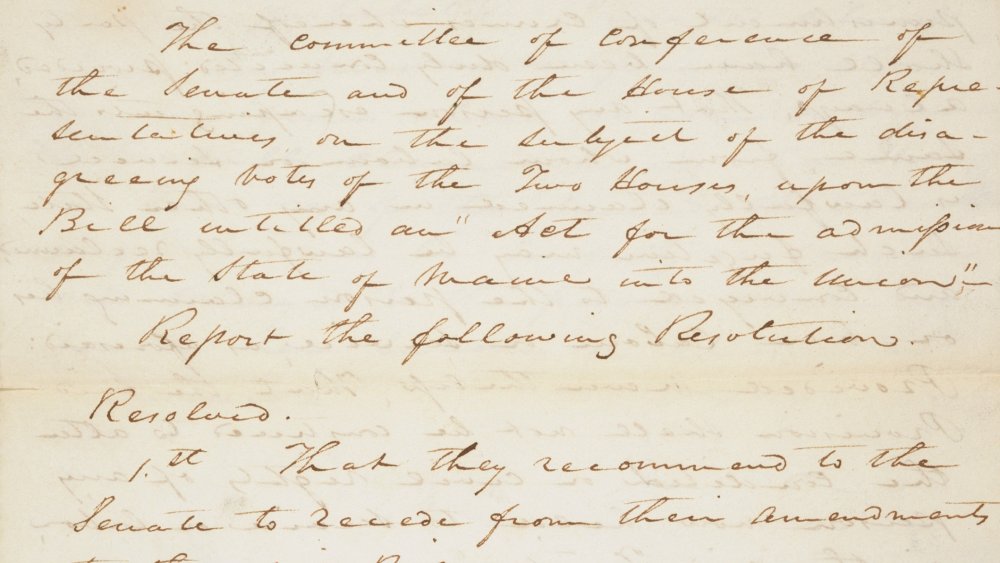

Whether or not Thomas Jefferson actually had the right to authorize the Louisiana Purchase under the United States Constitution as it stood at that time is another point of contention. As the National Constitution Center points out, the Constitution did not grant the Executive Branch the power to buy land from other countries. Jefferson took a political gamble when he sent the Louisiana Purchase treaty to Congress for ratification, where it passed after two days of debate. Some had reassured Jefferson that the deal was covered under the Constitution's Treaty Clause, which reads "the President shall have Power, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate to make Treaties, provided two thirds of the Senators present concur."

Regardless of its actual or implied constitutionality, as soon as the Senate ratified the treaty, Jefferson sent Lewis and Clark to find a route to the Pacific Ocean, according to the Smithsonian American Art Museum. This action further encouraged the manifest destiny philosophy that led up to Andrew Jackson's Indian Removal Act of 1830, which made explicit the legality of displacing Native Americans.

The Louisiana Purchase led to the expansion of slavery

Another tragic result of the Louisiana Purchase was the expansion of the United States' enslavement of Africans. As mentioned in National Geographic, Louisiana and New Orleans remained the slave trade hubs they were before the ratification of the Louisiana Territory as American-controlled lands. Farmers headed into the new territory with enslaved people and forced them to work on their farms, prompting a new round of debates regarding whether or not slavery should be legal in the United States.

Ironically, as Erin Blakemore reports at History.com, a deal inspired by France's defeat in the Haitian Revolution, which forced France to abolish slavery, led to 1820's Missouri Compromise. Here, lawmakers created a border between slave states and free states, legally expanding slavery into Missouri and adding pro-slavery politicians to Congress while adding Maine as a state that prohibited slavery — hence the "compromise." As Blakemore put it, this meant that "a slave rebellion helped drive the Louisiana Purchase, [but] the new territory was destined to become a place of suffering and exploitation for the thousands of slaves forced to work there."

The Louisiana Purchase led to the Civil War

There were, of course, people already living in the Louisiana Territory. According to Britannica, there were already between 50,000 and 100,000 residents, including mostly French-speaking colonists, enslaved Black people, free Black people, and Native Americans. The Smithsonian American Art Museum lists American tribal nations who lived on this land, including the Cherokee, Creek, Seminole, Choctaw, and Chickasaw. By the 1840s, the lands that made up the Louisiana Purchase were in a "constant state of war" between the colonizers and Native Americans, who were by then being forced from their homes by the United States Army as ordered by President Andrew Jackson. Britannica estimates that 70,000 Native Americans were relocated within the Louisiana Territory, and thousands of them died.

History.com explains that the Missouri Compromise was a temporary fix that made the South unhappy because it set a precedent for the federal government to make laws concerning slavery and made the North unhappy because it expanded slavery into new United States territory. According to Britannica, the tensions between the anti-slavery North and the pro-slavery South after the acquisition of the Louisiana Territory led directly to the American Civil War in 1861.