The Eastland Disaster: The Tragedy That No One Remembers

The United States is no stranger to disaster and tragedy, natural or manmade. Hurricane Katrina. California wildfires. Tornado outbreaks. The Great Chicago Fire. The sinking of the Titanic.

We remember all of those things, but strangely, there's one disaster that seems to have slipped through the cracks of our collective memories: the fate of the SS Eastland.

The what? Exactly. Somehow, the fate of the Eastland — and the hundreds and hundreds of people who lost their lives that day in 1915 — has sort of fallen out of our collective consciousness. And that's strange, especially considering that it claimed so many lives that it's among the worst maritime disasters in American history. It happened in Chicago, on July 24, 1915. Thousands of people woke up looking forward to a day of fun and relaxation, and within hours, 844 people were dead. So, what happened, and why have we largely forgotten about it?

It started out as a particularly fun, beautiful day

Disasters on any scale are horrible, but the Eastland disaster is even more terrible given the backdrop that it happened against. It wasn't just any normal day in Chicago, it was supposed to be an extra-special day, one that the employees of Hawthorne Works/Western Electric looked forward to all year.

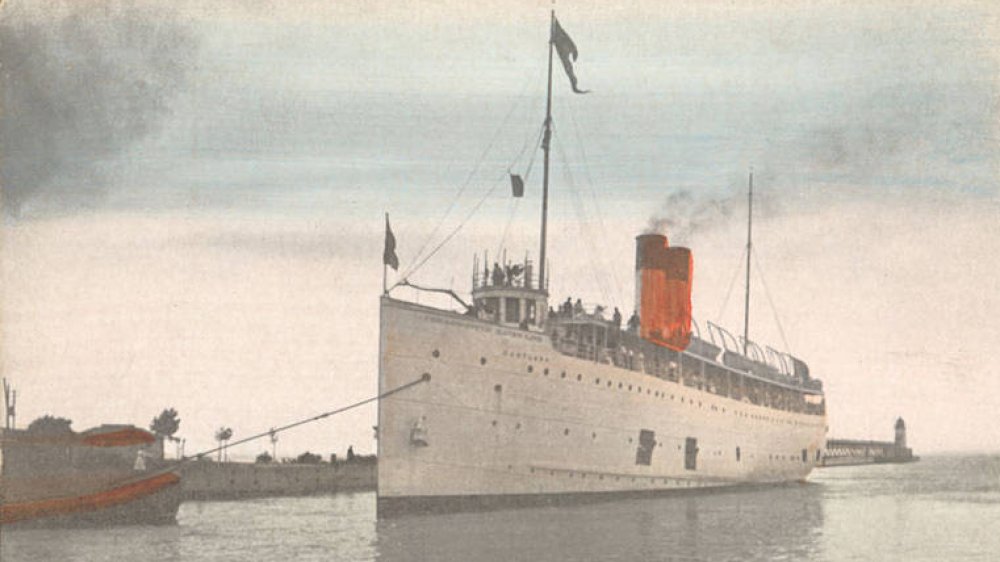

It was their company picnic, and remember, this was 1915. This was a huge deal: employees were looking forward to getting all dolled up, heading to the docks to board a passenger liner, and heading across the water to disembark in Michigan City, Indiana (pictured, the pier). There, they'd head to Washington Park, a brilliantly beautiful area with an amusement park, gazebos, plenty of places to picnic, a bandstand and dancing pavilion, and a bathing beach. Sounds amazing, right?

It was — especially for people who worked six days a week in the chaos of the city, it was a much-needed day of rest and relaxation. For families, it was the chance to get some quality time together, surrounded by the serenity of nature. For many young singles, it was the day of the year to mingle and meet people. And there were a lot of people to meet — more than 7,000 tickets to the event had been sold. According to the Eastland Disaster Historical Society, many were there bright and early — and the earliest started boarding the Eastland at 6:30 am. Rescue efforts would be underway just an hour later.

And things very, very quickly turned ugly

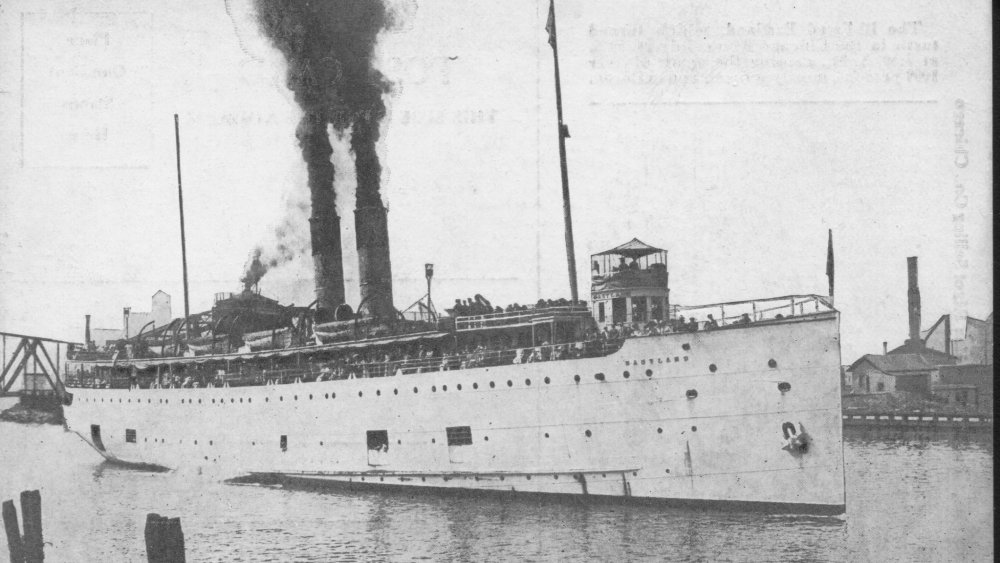

It's not clear just how many people were on board the Eastland when they pulled up the gangplank. According to navigation inspector R.H. McCreary (via Chicagology), his automatic counter hit 2,500 and he started turning people away. Other officials disagree, and say the number was closer to 3,200. Regardless of how many were on board, it was too many. The Smithsonian — who puts the number at 2,573 passengers and crew — says the gangplank lifted at 7:18, and preparations for setting sail were underway.

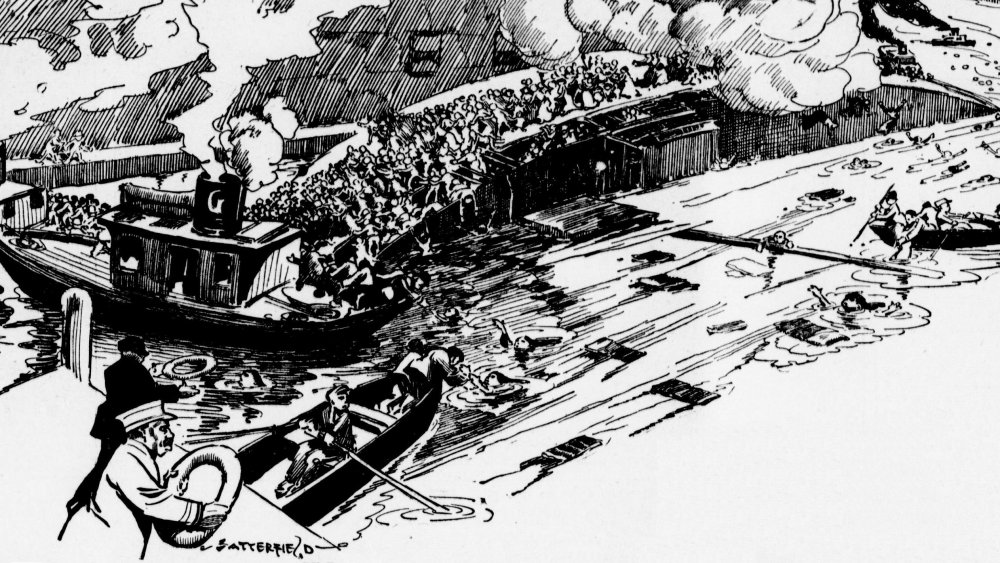

Between 7:10 and 7:15, the Eastland started to list. The ship righted itself for just a few minutes, and then — at 7:23 — it listed to port again. Those on board hardly noticed... until five minutes later, when it listed to a 45-degree angle. Water started pouring into the open portholes that were now suddenly at the water line, and just two minutes later, the ship rolled: one reporter described it: "like a dead jungle monster shot through the heart."

At 7:30, the Eastland had stopped moving: it was completely on its side. Some passengers — the ones who were still on the top deck — climbed over the railing and walked along the hull, jumping to the safety of dry land. Others were thrown into the water: "[...] the surface of the river was black with struggling, crying, frightened, drowning humanity. Wee infants floated about like corks." And more were trapped below.

How could such a thing happen?

It happened so fast, says the Smithsonian, that no one even had time to launch any of the life rafts that sat on the Eastland. And those life rafts? They were part of the problem. The Eastland had been built in 1902 — 13 years before she capsized. She was originally rated for 500 human passengers and cargo, along with six lifeboats. Reasonable enough, right?

Fast forward a bit, to 1912 and the sinking of the Titanic. When it became painfully clear just what could happen if a ship didn't have enough life-saving equipment, legislation changed to require enough lifeboats for 75 percent of passengers, along with life vests. For the relatively shallow-bottomed boats of the Great Lakes, that extra weight was a huge problem... especially for the Eastland, who underwent several changes to her carrying capacity. When she became a passenger-only excursion steamer, those numbers we mentioned? They look very different.

The day she rolled, she was carrying not only a few thousands more people, but five more lifeboats (for a total of 11), and 37 life rafts — and each weighed around 1,100 pounds. Oh, and there were 2,570 life jackets on board, too. It was all stowed on the upper decks, and that extra weight made her as top-heavy as an elephant on a bicycle. And here's the thing — she was unstable even before that. She nearly capsized in 1904 with 3,000 people on board, and again in 1906, while carrying 2,530.

The actions of nearby heroes was truly inspiring

Sometimes, disasters can turn ordinary people into heroes... so let's give some a shout-out. Morris Gault and William Corbett dropped what they were doing — one working at a nearby factory and the latter making laundry pickups — to start pulling drowning people from the river. They were joined by Abraham Blumenthal, a paperboy who immediately dove in and started dragging people to safety. Also on the scene was Laurence Frank Northrup, a nearby bridge-tender who hopped in a lifeboat and ended up saving the lives of 23 people (via the Eastland Disaster Historical Society).

Nearby boats joined in the rescue efforts, too. The captain of the Kenosha — the tug that was going to tow the Eastland out into the lake — ordered his boat be lashed to the dock, creating a life-saving bridge. The Indiana was among the first on the scene, too, and her captain suffered such nightmares after witnessing the horrors that day that he refused to discuss it. Bodies piled up on the Theodore Roosevelt as some of their crew helped the living, and the Carrie Ryerson was there, too.

Perhaps the best story is that of Charlie Hart, Johnny Benson, and FD Fredericks, employees of Dunham Towing and Wrecking. They had no experience with boats, but still commandeered a tug name the Rita McDonald... they figured it had an engine, and they could figure out how to drive it. They did — and they saved somewhere around 50 people.

Not everyone who died in the Eastland disaster was a passenger

It wasn't long before rescue efforts became recovery efforts, and the bodies that were plucked from the river were lifeless. Some, says the Eastland Disaster Historical Society, were revived: one man on board the Carrie Ryerson, Henry Oderman, saw a woman disappear beneath the water, and dove in to pull her to the surface. A coworker and fellow rescuer related, "It took us a long time to bring her to."

More and more boats arrived on the scene, and while some ferried the living to safety, others became what was described as "floating hearses." Bodies were piled on their decks and covered, then, the dead were taken to shore and transferred to one of the nearby buildings that had been turned into makeshift morgues.

And some of the rescuers gave their life for their efforts. The Eastland wasn't the only ship that had been chartered to take picnickers to their outing: waiting nearby was the Petoskey, and while most watched from the deck, a man named Peter Boyle dove into the river to aid in the rescue. Tragically, he, too, would ultimately be among the dead.

Volunteer divers had a horrible job

As the day dragged on and turned into night, those pulled from the water were more often dead than alive. The Eastland remained on her side, and the countless people who had filed below decks... they were still there.

The law enforcement and firemen on the scene were overwhelmed, so they started recruiting civilians — particularly those with diving experience. Or, in the case of one, excellent swimmers with no fear. His name was Charles R.E. Bowles, but everyone called him Reggie. By the end of the day, other divers had given him a new nickname: The Human Frog. The 17-year-old bystander went into the ship again and again, working through the day and into the evening, recovering 40 bodies before those older and wiser than he was forced the fatigued teen to stop, before he was among those lost.

According to the Eastland Disaster Historical Society, those who were recovered by the divers had little chance of surviving. One nurse that was on the scene, Helen Ripa, saw hundreds of people pulled from the water by divers like Dan Robbins, who recovered dozens of corpses while still hoping to find some survivors. Only a handful of people rescued by divers were able to be revived.

Stop ruining my ship!

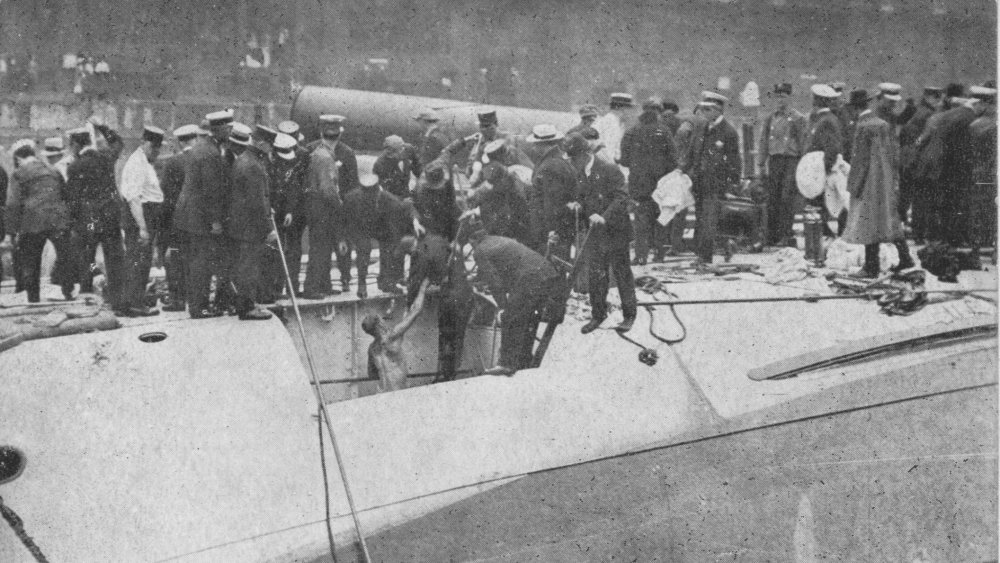

There was another group of heroes that stepped up that day: the welders. According to the Eastland Disaster Historical Society, countless lives were saved when welders working at nearby job sites grabbed their gear, dragged it onto the Eastland, and started cutting holes in her hull.

The hastily-cobbled-together plan, says Chicagology, was to cut eight holes along the length of the ship to free the people trapped within. Even though the thick steel, those standing on the hull could hear the screams of those inside — and when Coroner's Physician Joseph Springer told rescuers that many of the people they were recovering had suffocated, not drowned, it was decided that they needed to start cutting... quickly.

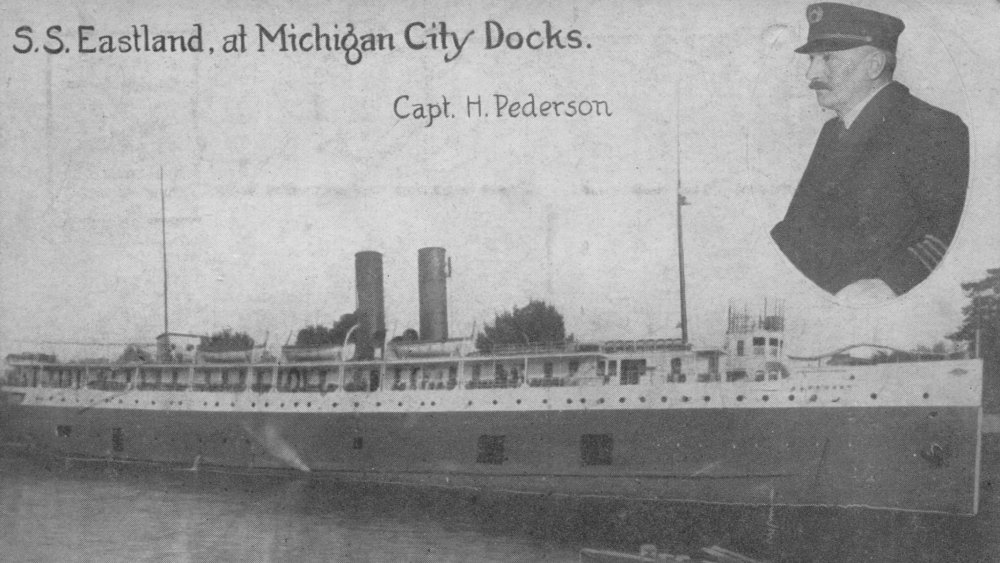

Dozens and dozens of people were dragged through the holes cut in the side of the ship, but here's the shocking thing: not everyone wanted to see it done. When Captain Harry Pedersen — who, notes the Smithsonian, was among those who stepped off the capsizing ship without even getting his feet wet — saw what they were doing, he met them with cries that they were "ruining his ship." Pedersen and at least 15 of his crew members interfered with the welders and rescue efforts so badly that the captain and his mate were arrested and removed from the scene... where a mob descended on them, getting a few good blows in before police diffused the situation.

Deaths by the numbers

When the dust and debris settled, 844 people were dead, but that only tells part of the story, says the Eastland Disaster Historical Society. Of the dead, 228 were teenagers, and 58 were infants and toddlers. A shocking 70 percent were under the age of 25, and when the ages of the victims were averaged? That average was just 23-years-old.

There were 175 women who went home that night as widows, and 84 men who ended the day as widowers. Three women lost not only their husbands, but the father of their unborn baby. An almost unthinkable 22 families were entirely destroyed that day. The largest was the Sindelars/Dolezal family: a mother and her sister, a father, and their five children all died.

Nearby buildings were converted into morgues, like the Second Regiment Armory. The Smithsonian says that as bodies were brought ashore, they were laid out in rows of 85. Then, there was the identification process: by the time midnight came, people were there searching for loved ones who had been on the boat. They went through the dead and checked if there was anyone they could identify.

Then, there were stories like that of Louis Schleiert. Chicagology says he was on the city's fire prevention bureau, and was one of the men cutting holes into the ship. He was looking for his wife and two children, who were all on the Eastland when it capsized. He found them: all three had perished.

The Eastland disaster brought out the worst in people, too

While there's a lot of good people who will give their all in the face of tragedy, there's a ton of jerks, too.

The makeshift morgues had a huge problem, and that was the fact that some people who just wanted to see the dead bodies shouldered their way in alongside the heartbroken, those looking for the family members they'd said goodbye to that same morning. Among the curiosity-seekers were another group, says the Smithsonian: the thieves and the pickpockets, who were there for one reason and one reason only — to steal from the dead.

And plenty more just wanted to look: local ferries and boat owners charged the curious between 10 and 15 cents for a ride past the disaster and its victims. The crowd that gathered just to watch was estimated at somewhere around 500,000 people, proving that everyone likes to get a look at tragedy.

The tragic tale of the Novotny family

According to the Smithsonian, all of the bodies were identified by July 29... except for one. He was a little boy who had been assigned the number 396, and who'd been given the nickname "Little Feller" by those who were trying to find his family. Why they had such difficulty became clear only after they transferred him to a funeral home, and he was identified by two of his schoolmates. He was little Willie Novotny, and he was 7-years-old. No one had come forward to identify him because his parents and his 9-year-old sister had died with him.

The Novotny family was just one of 22 families who all perished in the disaster; the Chicago and Cook County Cemeteries say that James and Agnes Novotny were immigrants from the Czech Republic, both born in 1879. James made $13 a week as a skilled cabinetmaker, and worked six days a week. The outing would have been some valuable family time, but they never returned. Instead, they were all buried together in the Bohemian National Cemetery on July 31, 1915. Around 15,000 people attended the funeral, including one of their only remaining relatives: Mrs. Frances Martinek, Agnes's mother.

The ship's owners got away without paying a penny

The Chicago Reader says that what happened with the Eastland wasn't just a disaster, it was an injustice. Why? Because karma turned a blind eye. Journalist Michael McCarthy has done a huge amount of digging into the story, and found that the extra lifeboats making the ship top-heavy was only the tip of the — ahem — iceberg. Documents in the National Archives revealed that the government had brought charges against the Eastland's owners, and presented evidence that they knew the ship wasn't actually seaworthy, and that it had been designed badly from the start. In fact, it was the only passenger ship that ever came out of its shipyard, and the architect? He was so inexperienced that he'd had to go back to his university professor for guidance.

The Eastland, it turned out, had been in for repairs for much of that season. Even though questions had been raised about stability, the answer came from the top: "Let's not hold up ticket revenues."

And don't worry, it gets worse. At the trial, the Eastland owners, crew, and engineers were represented by Clarence Darrow. (And yes, that's the name you recognize from the Scopes monkey trial, says PBS.) One thing you can say about him is that he was a talented lawyer: no one was ever held accountable for what happened, and the ship's owners got away with no repercussions whatsoever.

Why has history largely forgotten the Eastland disaster?

So here's a question: why have the history books pretty much forgotten about this massive maritime tragedy? The Titanic happened just a few years before, after all, and we all know about that. Chicago Magazine asked that very same question, and the answers are, well, kind of heartbreaking.

Jay Bonansinga, who wrote The Sinking of the Eastland: America's Forgotten Tragedy, called it the "blue-collar Titanic." And that says a lot about why people didn't care about it in the same way they cared about the Titanic: that was a massive ocean liner with a ton of rich and famous people crossing the ocean, while the Eastland was a little lake runabout with a bunch of everyday, blue-collar workers on board. And they weren't just blue-collar workers. Most of them were immigrants, many were from the Czech Republic. History simply hasn't seen them as important as some of the big names that went down with the Titanic, and at the time, they didn't even have the resources to fight for what they deserved.

Consider this: before the Eastland's owners went on trial, they hightailed it off to Michigan. They were tried there — instead of in Chicago, which may have been considerably less forgiving — and the people who lost everything that day simply didn't have the money, resources, or access to legal recourse that they should have. And that's pretty forgettable... even though it shouldn't be.

All of those who survived the Eastland have since passed away.