Tragic Details Of The Forgotten Osage Tribe Murders

It all started with oil. The dominion of the Osage tribe once stretched across the Ohio and Mississippi river valleys. During some territorial battles and nomadic shifts, the Osage moved towards the prairie-plains of Missouri and Arkansas.

In 1808, the Osage agreed to leave their lands in Arkansas and Missouri in exchange for a land base and compensation. From 1808 to 1865, the Osage Nation was forced to sign 10 treaties with the United States government that further diminished their land and pushed them onto reservations first in Kansas, then into Oklahoma.

Despite the fact that the treaties forced the Osage to cede their land in exchange for inadequate sums, the Osage Nation was able to recover its wealth. At the beginning of the 20th century, large quantities of oil were discovered under Osage land. The Osage quickly became known as "the richest people in the world," and this wealth soon drew the ire of white Americans. Many conspired to steal the wealth from the Osage and tragically, more than a few succeeded. These are tragic details of the forgotten Osage tribe murders.

When oil was first struck on Osage land

Roughly a decade before Oklahoma became a state in 1907, oil was discovered on the adjoining Osage Indian territory. After oil spouted from a well near Bartlesville, companies began rushing in to explore and excavate. But according to the American Oil & Gas Historical Society, this wasn't the first time that oil was discovered on American Indian territory.

After Edward Byrd, a Cherokee by marriage, discovered oil seeps in 1882, he organized the United States Oil and Gas Company with William B. Linn and a group of Kansas investors. They completed their first well in 1890, but the well was only producing a paltry half a barrel of oil a day, so Byrd's venture was soon shut down.

The 1897 Bartlesville oil gusher had more commercial potential than the previous oil pool, but it wasn't until 1899 when the Kansas, Oklahoma Central, and Southwestern Railway offered the ability to transport crude oil, that the oil industry boomed.

According to the Oklahoma Historical Society, mineral rights of the land were leased to the entire Osage Nation by Henry Foster on March 16th, 1896. Every Osage tribal member was entitled to one Osage headright, which gave them an equal share of the natural gas and oil royalty. Even though the Osage's lease was reduced in 1916, by that point there were more than 350 oil pools on Osage territory.

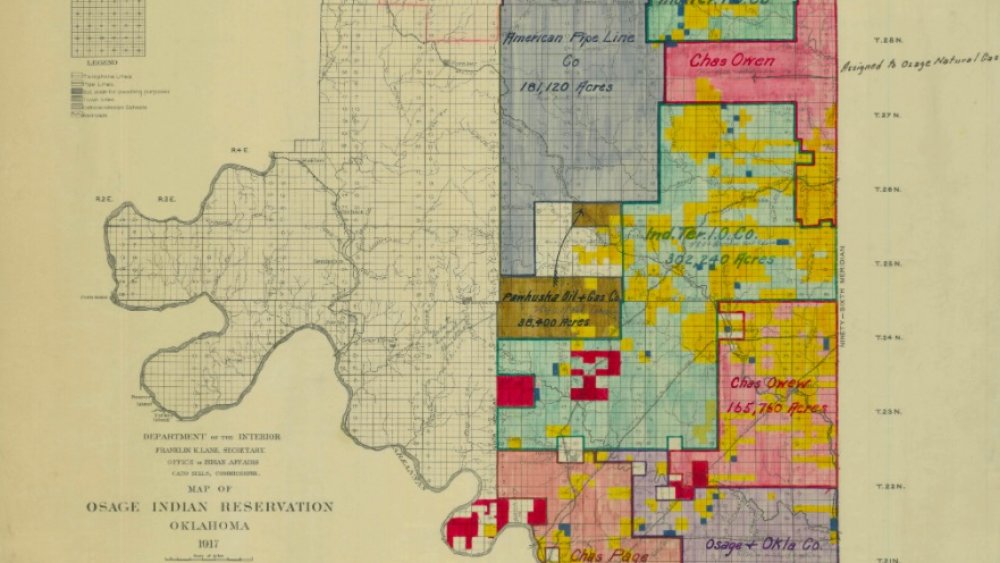

Carving up the Osage's land

In 1887, the government began breaking up Native reservation land into allotments to be given to individual tribal members with the Dawes Act. In 1906, the Osage Allotment Act similarly carved up the 1.5 million acre Osage reservation and the land was distributed to Osage tribal citizens. However, according to "Lands Allotted Among the Osage Indians" by Joseph F. Rarick, the Osage Allotments Act of 1906 was unique in that all of the reservation land was allotted. And since the Osage had purchased their reservation in 1870, their land was never partitioned as a result of the Homestead Act.

After each allottee selected 160 acres in three rounds, the rest of the land was divided amongst the allottees. This resulted in each of the 2,229 registered Osage citizens being allotted 657 acres each. And according to the Oklahoma Historical Society, mineral rights remained held in common despite the allotment of tribal land. Everyone who was on the original allotment registry, children included, was able to receive quarterly royalty payments from oil revenue.

The mushrooming wealth of the Osage

Over the years, tribal citizens of the Osage Nation earned millions through their mineral leases as the oil industry boomed. According to NPR, the Osage people received a check every four months. Initially, the amount was just a couple of dollars. Then it grew to $100, then $1,000, and continued to grow as more and more oil was tapped. In 1923, the 2,229 tribal members collectively earned $30 million, the equivalent of $400 million today. Tribal members were able to move into mansions, buy expensive automobiles, hire white servants, and send their children to study in Europe.

According to Billings Gazette, by the 1920s, each tribal citizen had an annual spending power of roughly one million dollars today. At the time, the Osage became the wealthiest people per capita in the world.

News stories were written about the "red millionaires" and "plutocratic Osage" who "instead of starving to death...[were enjoying] a steady income that turns bankers green with envy." Unfortunately, this mushrooming wealth caught the attention of many who wished to take it for themselves.

Government appointed supervision

Despite the fact that a judge acknowledged that Osage spent their wealth no differently from white people, the United States decided that the Osage people required supervision.

In what was essentially an attempt to control and acquire the growing wealth of the Osage Nation, Congress passed a law in 1921 requiring Osage to have "a certificate of competency" in order to receive royalties, removing restrictions against Osage who were "less than one-half" Native. Thus, according to NPR, anyone who was full-blooded or more than half-Osage was wrongfully deemed "incompetent" and assigned a guardian who was to receive the royalty checks instead.

According to Killers of the Flower Moon by David Grann, Congress also put a cap on how much money Osage with guardians could withdraw annually from their "trust fund." The guardians picked were typically considered "prominent white citizens [of] Osage County" and were often local attorneys or businessmen. This led to unparalleled corruption and abuse. Guardians came up with schemes to swindle money, such as buying cars and reselling them to their Osage "ward" at five times market value. Or they would outright steal from the Osage's funds.

According to The National Museum of the American Indian, by 1924, 600 guardians had stolen almost $8 million in Osage oil funds. And despite the fact that headrights were meant to protect the tribe, Congress also allowed headrights to be inherited by non-Osage if they had married an "incompetent" Osage, directly leading to the "Reign of Terror."

Five years of terror for the Osage

From 1921 to 1926, the Osage Nation was plagued with countless murders by white people seeking to gain headrights to Osage land. Known as the Reign of Terror, Osage tribal members were shot, poisoned, thrown off moving trains, or murdered through other horrifying means. While the official number of victims has been estimated between 27 and 60, the total number remains unknown.

While there is no clear-cut start to the Reign of Terror, suspicious deaths began to rise and become more outrageous during the period. According to Tulsa World, some of the victims included Henry Roan, who was found in his car, shot in the back of the head, Anna nee-Kyle Brown, who was found in a ravine also shot in the head, and Bill and Rita Smith, whose house was dynamited.

Those who had information on the murderers were also targeted. In 1923, George Bigheart, ill from being poisoned, gave information about a recent murder to local attorney W.V. Vaughan. A mere 36 hours later, Vaughan's body was found with a broken neck.

According to NPR, even those who were friends of the Osage were targeted. Barney McBride was a white oilman who went to Washington, DC on behalf of the Osage in 1922. Trusting him, the Osage asked McBride to go to the nation's capital to ask for the government's assistance in addressing the rampant murders. The evening after McBride arrived at his boarding house in DC, he was abducted. The next morning, his body was found beaten, stabbed, and stripped naked in Maryland.

The Bureau of Investigations gets involved

In 1923, the Osage once more sent people to Washington, D.C., pleading for the Department of the Interior to help investigate the countless killings. On March 24th, the Office of Indian Affairs made an official request to the United States Bureau of Investigation, which would later become the FBI, to investigate.

According to The National Museum of the American Indian, the Bureau of Investigations sent in four agents to work undercover from 1923 to 1925 as an insurance salesman, a cattleman, an oilman, and a medicine man. According to Famous Trials, Tom White, the head of the Bureau's office in Houston, was the only one who was there openly as a Bureau investigator.

Interviewing more than 150 people, the agents were unable to gather much evidence outside of unsubstantiated rumors. Many were scared to say anything directly out of fear of being the next victim. And by this point, trust in law enforcement had been thoroughly eroded and the agents had to rebuild the Osage's confidence in their services. But slowly, people began to come forward and admitted to the agents their fear of William K. Hale and his faction.

The criminality of William Hale

During their investigation, Bureau agents discovered that William K. Hale, who called himself the "King of the Osage Hills," was responsible for instigating a majority of the Osage murders. Born in Texas, Hale was a cattleman who had settled on the Osage reservation in the late 1800s and through intimidation, bribery, and extortion, had risen to local prominence.

According to Bostonia, Hale encouraged his nephew, Ernest Burkhart, to marry Mollie Brown, a full-blooded Osage woman. Brown's husband had previously been Henry Roan Horse, also known as Henry Roan, who was found murdered in 1923. According to Famous Trials, Hale also happened to be listed as the beneficiary on Roan's life insurance policy for the amount of $25,000. Hale even served as a pallbearer for Roan's funeral and afterward encouraged local law enforcement to build a case against Roy Bunch, a man whom he'd tried to convince Roan was having an affair with Mollie.

According to Killers of the Flower Moon by David Grann, before Roan's death, Hale had taken him to a doctor. The doctor reportedly asked Hale, "Bill, what are you going to do, kill this Indian?" to which Hale had responded, laughing, "Hell, yes."

Mollie Brown and her family were one of the main targets of William Hale as he tried to usurp her family's headrights to the land.

The tragic fate of Mollie Brown's family

Mollie Brown had married William Hale's nephew, Ernest, in 1919, which Tom White began to suspect was the first step in Hale's nefarious plot.

Mollie's sister Minnie was possibly Hale's first victim from the Brown family. According to Famous Trials, Minnie had died in 1920 from "a peculiar wasting illness," despite having been in perfect health beforehand. Three years later, Mollie's other sister Anna was found dead on May 28th, 1923, one week after Mollie had last seen her leaving with Bryan Burkhart, Ernest's younger brother.

In 1923, Mollie's mother Lizzie Q was also growing weaker. Lizzie died in July and many thought that she must've had the same strange disease to which her daughter Minnie had succumbed. However, Bill Smith, Mollie's brother-in-law, suspected that the family was being poisoned.

Bill Smith was married to Mollie's sister, Rita, and was fiercely outspoken about his belief that there was a murderer among them. According to PBS, in the early hours of March 10th, 1923, a bomb went off underneath the Smith's house, killing Rita instantly. Bill hung on for several days, but his wounds proved to be too great.

Mollie Brown was also in the process of being slowly poisoned. White and the other agents arranged for her to be taken to a hospital outside of Hale and Burkhart's influence and as she recovered, it became clear who was responsible.

The barest of convictions

On January 4th, 1926, warrants were issued for William Hale and Ernest Burkhart. While in custody, Ernest Burkhart confessed to Tom White that his uncle Hale was responsible for the bombing of the Smith house. Ernest also told White that Hale had hired John Ramsey, a contract killer, to murder Henry Roan.

According to the Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History & Culture, that month federal agents took Hale, Ernest Burkhart, and Ramsey for the murders of Bill Smith, Rita Smith, and Henry Roan. In April, they would also charge Kelsie Morrison and Byron Burkhart for the murder of Anna Brown.

Hale ended up being tried three times for the murder of Roan, with the first trial ending in a hung jury and the second being reversed on appeal. Eventually, after several trials, perjured testimonies, and tampered juries, the sentences were handed down. Hale, Ramsey, and Ernest Burkhart were all given life sentences, but Hale and Ramsey were released on parole after only 20 years in prison. Ernest Burkhart was also released after 11 years and ended up being pardoned by Governor Henry Bellmon.

According to the Skiatook Journal, while Morrison was found guilty of the murder of Anna Brown, his case was reversed and dismissed due to a technicality, since he had apparently had immunity while testifying in Ernest Burkhart's trial.

Countless Osage murders remain unsolved

Although William Hale was likely responsible for dozens of murders, he was only convicted for the murder of Henry Roan. As a result, many went unsolved and the number of total murders is still debated to this day.

According to This Land Press, despite the fact that the Bureau considered the arrest and conviction of Hale a judicial success, the bodies of murdered victims kept surfacing during and after the trials. Many of the murders weren't even considered by the Bureau or listed in their files, such as the murder of Paul Pierce. According to Pawhuska People, Pierce had gone to Attorney Comstock about a divorce because he suspected that his wife, a white woman, was poisoning him. Afterward, in 1927, he was killed in a hit and run and a third of his headright went straight to his former wife. Pierce's granddaughter, Mary Jo Webb, suspects that the murders began even before 1921, which would bring the tally of those targeted and murdered into the hundreds.

Webb has done independent research of her own. While she never consolidated her material into a book, in the 1990s, she compiled an exposé on the murders. In it, she named the names of some of those responsible for the murders who avoided prosecution and put the document in the Fairfax Library in Oklahoma. The document ended up going missing and shortly afterward she got an anonymous phone call, threatening to murder her.

An attempt to prevent further bloodshed

After the investigation and conviction of Hale, the head of the Bureau of Investigation, J. Edgar Hoover, eagerly took credit for Tom White's investigatory work. Hoover also thought it would be appropriate to send the Osage a bill for more than $20,000.

In a meager attempt to prevent another Reign of Terror, Congress amended the law to disallow non-Osage from inheriting land rights from Osage tribal members. On February 27th, 1925, H.R. 5726 was passed, which stated that "none but heirs of Indian blood shall inherit from those who are of one-half or more Indian blood of the Osage Tribe." However, this Act exempted spouses who had married before the passage of the Act.

According to Tulsa World, in 1978 Congress passed another law that made the transference of headrights from an Osage to a non-Osage person or entity illegal. Unfortunately, immeasurable damage had already been done. And according to Indianz, out of the original 2,229 headrights, the Osage managed to retain only one-fourth.

Settlements rarely settle anything

While the oil industry doesn't produce the wealth that it once did, many Osage still receive a quarterly royalty payment. Despite everything, the United States government continues to hold the Osage's wealth in a trust. This came to a head in 2000, when the Osage Nation brought a lawsuit against the Department of Interior for mismanagement of the Osage's trust funds and non-monetary assets. According to Tulsa World, the case lasted over a decade in courts, ending with one of the largest tribal trust settlements in United States history in 2011.

According to Indian Country Today, the United States reached a settlement with the Osage to the tune of $380 million, to be distributed evenly among those who own headrights. Tragically, during the time it took to litigate the case, 20 Osage holders of headrights passed away. Plus, between 25 to 30% of headrights owned today are owned by non-Osage, whose ancestors more than likely got those headrights through murderous means.

In 2002, the Osage also filed Fletcher vs. United States, which also alleged a history of mismanagement by the federal government. Although the Northern Oklahoma District Court ordered the United States to give an accounting of the trust account to the Osage Tribe in 2015, the Osage were still pushing to see the accounting in 2017. Unfortunately, according to Indianz, in 2017, it was ruled that the accounting would only go back to 2002 because going back to 1906 "would take too much time and cost too much money."

![Peter Bighart [sic], chief of the Osage tribe, 1909](https://dvmmoms.com/img/gallery/tragic-details-of-the-forgotten-osage-tribe-murders/five-years-of-terror-for-the-osage-1598987627.jpg)