What It Was Really Like Being An Old-Timey Chimney Sweep

Being an old-timey chimney sweep is one of those quaint, Victorian-era jobs that couldn't have been too bad ... right? Especially when you're comparing it to things like leech collector (collecting leeches), a tosher (hunting for treasures in the raw sewage under the city), grave robber (usually on behalf of local medical schools), and pure finder. That last one doesn't sound familiar? Mental Floss says those were the people that collected dog poop for use in the leather-working trade. Still think you'd like to live back then?

Chimney sweep sounds like it might be a not-so-terrible option, right? Wrong. It's almost shocking just how much horrible stuff got folded into the everyday life of both master sweeps and their apprentice sweeps ... but mostly, the apprentice sweeps. Can you say anything good about their lives? Not really, aside from the fact that oftentimes, their miserable existences were mercifully short. Think that's dark? Wait until you learn more about the sad, scary, dirty life of the chimney sweep.

Chimney sweeps were probably apprenticed into a miserable life

Apprenticeships were agreements that — in theory — allowed children to learn a trade, while the master tradesman got some free labor. According to Owlcation, apprentice chimney sweeps of the Industrial Revolution and Victorian era (between 1760 and 1901) were some of the most widely — and badly — abused.

Many families were poor, and the number of children who were looking for apprenticeships was high, which meant master tradesmen had the pick of the litter, so to speak. And master chimney sweeps tended to choose a very specific type of child: the smallest and most underfed children, preferably those with no parents or parents who weren't exactly in the picture.

What happened next tended to depend on where you were. In Scotland and most countries across Europe, apprentice sweeps were taught to use a contraption that was basically a lead ball and a brush attached to a rope for cleaning the chimneys. If you were unfortunate enough to be in England or Ireland, though, it was the child that was going up and down the chimneys.

That's one reason why the children were so young: the youngest apprentice (that history remembers) was reportedly just three and a half years old when he signed on. Most were 5 or 6, for a terrible reason: they were still small enough to fit in the chimneys, but they were old — and tough — enough to give them a fighting chance to survive the ordeal.

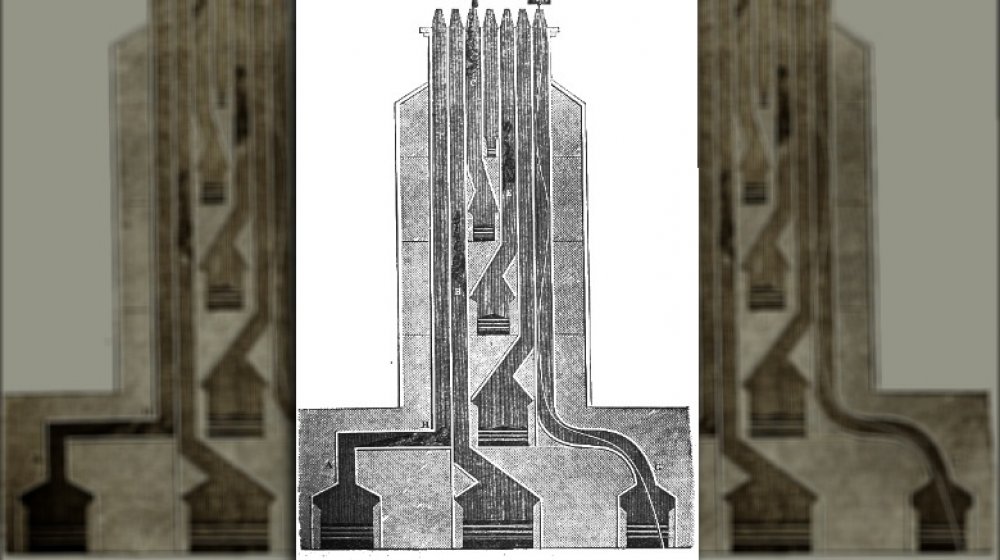

Victorian-era chimneys were a nightmare

Let's talk about just what kind of chimneys Victorian-era apprentices were being sent into because they were nothing like the straight, single chimneys we think of today.

Chimneys in the cities were often installed in old buildings, which meant that they were far from straight. They were typically angled to avoid cutting through living spaces, and most were around nine inches by 14 inches in size ... if they were lucky. It wasn't uncommon for chimneys to be only about seven inches square, and go ahead and measure that out. We'll wait.

Tight spaces and extreme angled corners weren't all sweeps had to deal with, either. It wasn't uncommon for chimneys to be around 60 feet tall, so death from falling wasn't unheard of — and that's a fall either back down the chimney or off the roof once they got out.

And here's one more horrible fact: Owlcation says that flues were often connected, particularly at the top. The reason? A 1664 law that said any roof with more than two chimney tops was taxed extra, so they were often combined. The result was a labyrinth of chimneys that a sweep could get lost in — and they often did, because sweeps didn't just climb up the chimney, they had to climb back down. A wrong turn could be deadly ... and so could losing your bearings and starting down the wrong chimney right from the roof.

Chimney sweeps were motivated to work in cruel ways

Owlcation says that complicated Victorian chimney systems built up soot pretty quickly, and many needed to be cleaned as many as four times a year. It's not entirely surprising, then, to learn that a single chimney sweep might be responsible for cleaning not just one or two chimneys a day, but as many as 20.

If children thought they were going to slow down in protest, they would be sorely mistaken ... literally. (Keep in mind that these kids had absolutely no reason to try to do the best job possible: Victorian Children claims that those who weren't sweeps by apprenticeship were often orphans plucked off the streets, or they were downright kidnapped into slavery.) Master sweeps had some definitely unpleasant ways of getting children to hurry up, and according to The Local Chimney Sweep, that included carrying a sharp stick that was used to prod the feet of children who were hesitant about climbing.

Once they were out of stick range, it wasn't unheard of for a master sweep to just light a fire in the fireplace to encourage a child to work faster.

It's a hard-knock life for chimney sweeps

Some bumps and bruises come with the territory when you're a kid, but it's tough to stress just how horrible the life of an apprentice sweep was. Owlcation says that typically, sweeps in the country had it better than those in the cities, and those city kids? Life was awful, especially when they were just starting.

While some masters would give their kids pads for their knees and elbows, others simply didn't bother. And sometimes, the chimneys would be so narrow they needed every bit of space they could get, which meant shedding their clothes and climbing naked, save a cap worn to keep the worst of the soot out of his (or her) face.

Sounds painful? It was: if the chimney was hot, the master sweep would often stand on the roof — in case he heard the child screaming, he'd be there to pour water down the chimney. When the children emerged, their elbows and knees were often raw and bleeding. In order to toughen them up, the master sweeps would force the development of hard calluses by purposely scraping them with a stiff brush dipped in brine — and it was a treatment that could take months or even years.

Other master sweeps would simply wash their wounds with salt water, and then send them on to the next chimney (via Victorian Children).

Yes, there was definitely a risk of getting stuck in a chimney

In spite of the fact that many master sweeps deliberately underfed their apprentices so they remained small, they definitely got stuck: a lot.

One slip, says Owlcation, could result in the child's legs getting stuck beneath them, wedging the apprentice in the chimney. If that happened, another apprentice was sometimes sent up to tie a rope around their legs and try to pull them out. That risked the loss of two sweeps because there are instances of both boys dying inside the chimney.

Suffocation was a very real danger, too, either from falling soot or from becoming wedged too tightly in the chimney to be able to breathe. Burns were also a common cause of death, along with falling from rooftops. The chimney sweep's busiest season was usually around the holidays when people were preparing for Christmas parties, and the cold, damp weather played havoc with already aching joints, with an even greater risk.

Think it can't get worse? It can! According to The Local Chimney Sweep, when a child did die in a chimney, recovering the body sometimes meant breaking a hole through the wall and chimney, and that was up to the homeowner to decide whether or not they wanted to do it. Sometimes, a careless master wouldn't even notice their apprentice had gotten stuck or died, and the sweep would be left to starve or burn to death when the fire was lit, per London's Pulse Projects.

There's a reason it's called chimney-sweep cancer

While it might be a given that being a chimney sweep is a dirty job, that's just the start of it. According to The Lancet, children working as apprentice sweeps weren't just often forced to climb 60-foot chimneys without even the protection of clothes, they would typically only bathe once a year. Being covered in soot and creosote 24/7 isn't just unhealthy, it's downright dangerous. In the late 1700s, the prevalence of a particular type of cancer in chimney sweeps became very evident.

The Royal Society of Chemistry says that it was a doctor named Percivall Pott who made the connection: chimney sweeps had a high likelihood of developing a type of cancer that first developed in the scrotum, was first mistaken for a venereal disease, and would ultimately spread to the abdomen and cause an unthinkably painful death.

The cause? The soot that inevitably became lodged in the folds of skin. By 1788, the problem had gotten so bad that Parliament passed a law stating that chimney sweeps should be no less than 8 years old, and be bathed at least once a week. It didn't seem to do much good: between 1880 and 1890, 29 of the 39 cases of scrotal cancer treated by St. Bartholomew's Hospital in London were in sweeps, and by 1910, it was the cause of death listed for around 29 percent of chimney sweeps.

Chimney sweeps had a lifetime of devastating health issues

The life of a chimney sweep wasn't just miserable when they were on the job, it was miserable all the time thanks to the myriad of health issues they tended to be plagued by.

For starters, there were the immediate problems. Northeastern Chimney says that because children were put to work so young and forced to spend so much time in cramped spaces, they often grew disfigured as they matured. Their growth was often stunted, their joints were a constant source of pain, and vision problems were fairly constant, too. Chronically sore eyes were on the better end of what they could hope for, and some eventually went blind from the soot particles.

Owlcation says many suffered from chronic respiratory troubles, with many developing breathing problems so severe they became deadly — particularly when the weather turned cold. Then, there was the chance of developing a fungal infection in the lungs called histoplasmosis. The source? The birds — and their droppings — that were around in slightly smaller quantities than soot.

Then, there were the long-term problems, the ones that didn't show up for a while. London's Pulse Projects found that chimney sweeps suffered from abnormally high rates of lung, esophageal, and liver cancer, along with leukemia and mesothelioma.

Finding customers and running a side business as a sweep

The chimney sweep's day was very, very long: Owlcation says that it typically started at around 5 am, which gave sweeps time to get to a decent number of chimneys before the day's fire was lit beneath them. And it wasn't even just about sweeping chimneys, as there were other duties, too.

For starters, apprentice sweeps were expected to drum up new customers. They did it the old-fashioned way: by heading out into the streets and shouting, "Soot-o! Sweep-o!" to remind anyone in earshot that it was probably time to get their chimney tended to.

Apprentice sweeps were also responsible for collecting the soot they cleaned out of chimneys. Each was typically given a blanket to collect the soot from each chimney. The soot would be carried back to the master sweep's home, dumped outside, then sifted and broken up into dust. That, in turn, would be sold as fertilizer.

And yes, that's the same blanket the children would sleep under at night. Their sleeping arrangements varied, but city sweep could expect a pallet of straw, their soot blanket, and a few other children to huddle together with for warmth. It was so common it was called "sleeping in the black," because everything about them was soot-black.

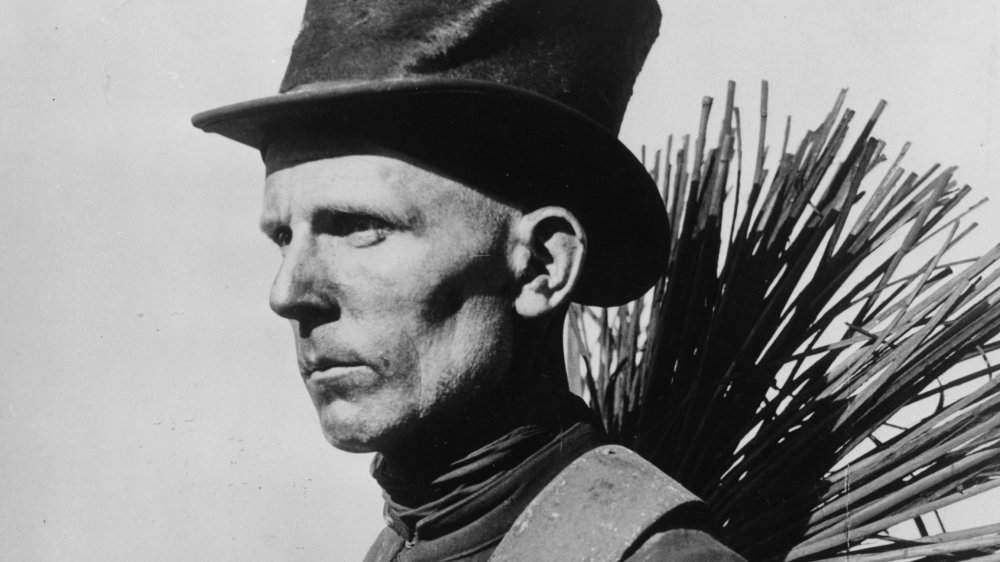

What's with the top hat and tails many sweeps were wearing?

If there was ever an unlikely-sounding uniform for a chimney sweep, it's the top hat and tails. But in old photos, so many of them seem to be wearing this dapper sort of dress. What's up with that?

Baun's Chimney Sweeping claims there are actually a few stories associated with sweeps' preference for such fancy clothes, with one oft-repeated tale going back to King George. He was riding his horse when it was spooked by a dog, and a quick-witted sweep grabbed the reins and calmed the panicked animal. By way of thanks, the King decreed that sweeps were allowed to wear top hats — and that was a right usually reserved for the upper-class.

It's uncertain just how true that is, but there's another story that seems a bit more believable. Being a chimney sweep was dirty work, and people tended to look down on the people who did that sort of thing. In order to raise their profile and make them a little more respectable, the story goes, it was decided that chimney sweeps would start adopting the cast-off, worn-out, discarded clothes of funeral directors, which was usually the super stylish combination of the top hat and black coat.

Regardless of how it happened, it wasn't long before it was tradition. Most chimney sweeps would have worn something of the sort, and it was a practical tradition, too: the soot blended right in.

Chimney sweeps could get a side gig being lucky

Let's fast forward a bit and come out of the Victorian era. It turns out that chimney sweeps have a reputation as being lucky, to the point where if you were one, you could probably pick up some extra cash with a side gig of just, well, being good luck.

According to Midtown Chimney Sweeps, there are a few legends that account for the sweeps' lucky image. For starters, there's the legend that says a sweep saved the life of William the Conqueror and was invited to his daughter's wedding. A great story, but very unlikely to be the least bit true.

Another story tells the tale of a sweep who fell off a roof and was dangling from a gutter when he was rescued by a fair maiden who pulled him into her window. They fell in love and ended up getting married, and if that's not lucky, what is?

As there's a wedding in both of those stories, it's not surprising that it's long been said to be good luck to have a chimney sweep at your wedding, and some sweeps were hired specifically to attend weddings. It's also said that after a sweep has cleaned your chimney, it's good luck to touch his buttons, kiss him (or blow him a kiss, as they say in Mary Poppins), or to just shake his hand.

Chimney sweeps weren't saving the lives of any Conquerors

Let's talk about a brief bit of chimney and chimney sweep history because it'll help clear some things up. There's a popular story about how a chimney sweep changed history in 1066 during the Norman conquest of Britain when he saved William the Conqueror after his horse bolted. According to The Local Chimney Sweep, that's just not true for the simple fact that at the time, homes didn't have chimneys that needed sweeping.

According to the Ultimate History Project, chimneys first showed up around the 12th century. By the time Elizabeth I was on the throne, she would still send guests to neighboring homes that had chimneys, and it wasn't until the 1700s that Benjamin Franklin helped make chimneys more efficient. By the Victorian era, well, that's a whole different story.

Still, it's worth talking about exactly when chimney sweeps started their perilous work. Early chimney sweeps were probably around in the 16th century, but it wasn't a common job. Many people would simply clean their own chimneys, sometimes by throwing a chicken or goose down, or pulling bunches of holly through.

It wasn't until 1666 — when the Great Fire of London destroyed a huge part of the city — that people began to realize it was a job for the professionals. Enter: the chimney sweep, but the job wouldn't have any legal protections for almost two centuries.

If you lived into the 19th century, you had some protections

Being a chimney sweep — and particularly, being an apprentice — was always pretty awful. If you managed to live into the 19th century, you would have seen legislation starting to be passed with the ultimate goal of protecting you ... but how well they did at enforcing laws was another matter.

Intriguing History says that the Chimney Sweeps Act of 1834 was passed to try to stop the widespread abuse that most apprentice sweeps labored under, and forbid apprenticing children under 10. The problem? There really wasn't anyone employed to monitor the industry.

It quickly became clear that there were still problems, and another act was passed in 1840 that was supposed to issue more protections, but even Parliament says that it really didn't. There was yet another law enacted in 1864, but it wasn't until 1875 that all chimney sweeps were required to be licensed, and this time, it was enforced by police.