These Spies Were Never Brought To Justice

Seriously, who doesn't love a good spy thriller? The chase, the mystery, the close calls, the uncertainty of whether or not our hero or heroine is going to make it back to safety... (spoiler alert: it's a movie, they probably will.) But here's the thing: those movie spies don't have anything on the real deal.

History is full of stories where spies changed the course of wars — and history itself — through their covert operations. And they've been used for a long time. Even Sun Tzu, the military strategist who lived around 500 BC, touted their usefulness, writing (via Sacred Texts): "[...] it is only the enlightened ruler and the wise general who will use the highest intelligence of the army for purposes of spying, and thereby they achieve great results. Spies are a most important element in war [...]"

Especially when they don't get caught. While there's a ton of stories of spies who were brought to justice by those they were stealing secrets from, there are also spies who were so good at what they did they got away scot-free... and some lived happily ever after.

From New Mexico to Moscow

In 1985, Edward Lee Howard gave the federal agents pursuing him the slip and disappeared into the New Mexico desert. Less than a year later, he reappeared: in Moscow, where the ex-CIA agent had been given asylum.

According to the New York Times Magazine (via the CIA), Howard was the first CIA agent known to have defected to the Soviets — and the consequences of his actions were deadly. Howard, it was reported, had spilled the beans on some of the top secret methods the CIA used to contact and communicate with their undercover agents, which led to the expulsion of a number of spies who had been working for the CIA, and the execution of at least one. Adolf Tolkachev was a Soviet defense researcher who had been passing info to the US regarding Soviet advances in defense technology, and was discovered, tried, and executed as a result of Howard's betrayal (via the CIA).

The CIA was suspicious and did ultimately fire Howard after a questionable polygraph test, and at least one agent knew of Howard's switch in allegiance: William G. Bosch. Even as agents were questioning Bosch, Howard was planning his escape with help from his wife. And escape, he did. After showing up in Moscow, Howard was given an apartment, continued his pattern of alcohol abuse, and according to The New York Times, it was reported that he died in 2002.

Evacuating? I think I'll just stay behind...

Some stories make you wonder how such a thing can happen, so this one's worth a little background. By the time Pham Xuan An was hired by Time in 1966, he already had a long-standing association with the Viet Minh, and had worked for both the CIA and the South Vietnamese Army. He was officially made a full-time staffer in 1969, and when that happened, he became the first Vietnamese reporter covering the Vietnam War for an American news outlet.

As such, The New York Times says he had access to things like off-the-record briefings by American military officials. At the same time he was covering those events and writing about them for Time, he was also doing a different kind of writing: the kind that was done with invisible ink, and on materials left at drop points for the Viet Cong, in what was then the city of Saigon. In hindsight, CBS News's Morley Safer called him "among the best-connected journalists in the country," and then quoted him as saying that he had passed along information unit strengths and weaknesses to political happenings.

His escape was simple: when Time pulled their correspondents out on April 30, 1957, he stayed behind. That was literally it. It wasn't until after the war that the truth came out, and his colleagues still lauded him for his journalistic capabilities. He died in 2006, at 79-years-old.

A mysterious betrayal and no regrets

According to the Smithsonian, no one's sure who betrayed Oleg Gordievsky. We do know, though, that things went sideways on May 17, 1985 — the day he got a cable ordering him to report to Moscow to meet with the KGB... supposedly to discuss a promotion. He later wrote, "Cold fear started to run down my back, because I knew it was a death sentence."

Gordievsky had been passing information to the British — Haaretz says that the information he provided shaped the course of the Cold War. And he had been betrayed, but he wasn't absolutely sure of that when he went to Moscow — encouraged by his handlers from MI6. He was confronted several times, and finally pulled the proverbial rip-cord: cutting open the cover of a book, he headed to the specific street corner he'd been directed to, and finally saw a man carrying a bag from Harrods while eating a candy bar. It was go time. After a series of trips by rail, train, bus, and taxi, he met three British agents who were driving a modified Land Rover. Stashing him in a secret compartment, they drove across the border to Finland... and freedom.

The Guardian talked to him in 2013, and the 74-year-old ex-spy was still living in London. His finger was still on the pulse of the espionage scene, and said he had no regrets about betraying his homeland: "Everything here is divine."

Iowa-born, with Soviet loyalty

According to the Smithsonian, it wasn't until the 21st century that the west started to realize the importance Soviet military intelligence (GRU) had played in the development of their nuclear weapons. That's perfectly illustrated by an award Russian President Vladimir Putin gave in 2007. The recipient was Zhorzh Abramovich Koval, a man who'd been a private when he'd left the Red Army in 1949. He was given a gold star — making him a Hero of the Russian Federation — and the Western world said, "Wait a second, what now?" Koval had just been unmasked as a spy codenamed Delmar.

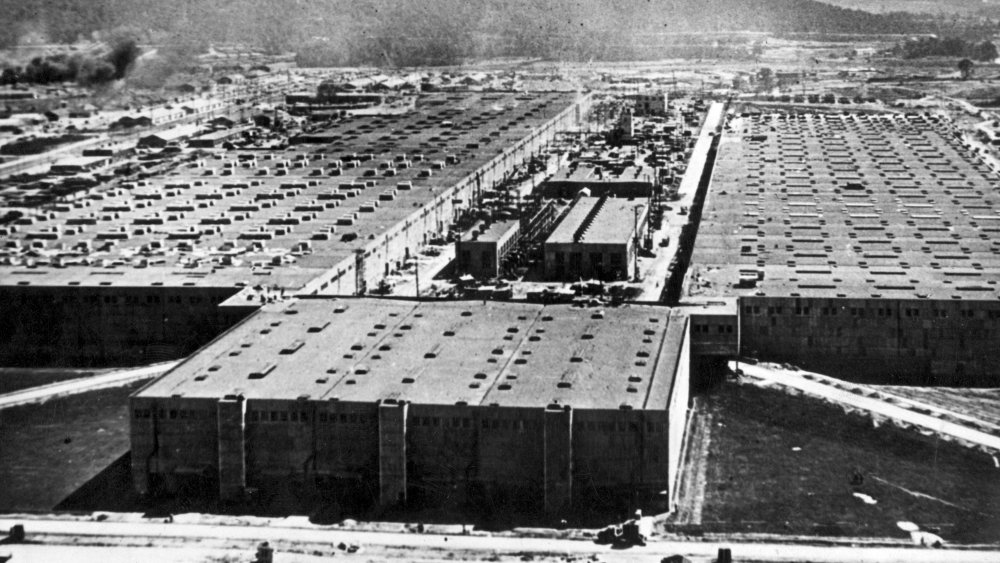

Born George Koval, the Iowa native and his parents had emigrated to the Soviet Union in the middle of the Great Depression, and his skills as a mechanic got the attention of the higher-ups. He was ultimately recruited, assigned a codename, and sent back to the US where he studied electrical engineering and ended up working at the Oak Ridge nuclear facility (pictured). After spending several months passing along information about the program's top secret research, he was transferred to an equally secret facility in Ohio. According to Atomic Heritage, it was there — as a health physics officer — he started collecting and sharing things like the process for manufacturing polonium.

He was discharged from the Army in 1946, got another college degree, and sailed away in 1948. Literally: he never returned to the States, and died in Russia in 2006.

The great escape of the Limping Lady

In the case of Virginia Hall, the justice she escaped was some Nazi justice that would have been undoubtedly horrible, and how she did it was incredible. For starters, the Smithsonian says she was a very unlikely spy for one simple reason: she was very noticeable and easily recognizable, thanks to a wooden leg she'd gotten after a hunting accident. She'd named her leg Cuthbert, and had a pronounced limp — hence, her nickname.

It definitely didn't matter to her. After she was recruited by the British Special Operations Executive, she set up camp in Lyon, France — which is where she got down to business. The Maryland native — who had her application to the US State Department rejected on the basis of her disability — started recruiting people into the French resistance. She also led an expedition to free a dozen associates from an internment camp, drove ambulances on the front lines, and caught the attention of the Nazis: specifically, Gestapo chief Nikolaus Barbie.

The Washington Post says that it was when the so-called Butcher of Lyon started closing in on her that she decided she needed to get out of France the only way she could — by grabbing a backpack and hiking over the Pyrenees Mountains. She made it to Spain — where she was arrested for not having a passport — then went back to France to help with D-Day preparations. The Nazis never caught her, and she died in Rockville, Maryland, in 1982.

The spy who helped assassinate Abraham Lincoln

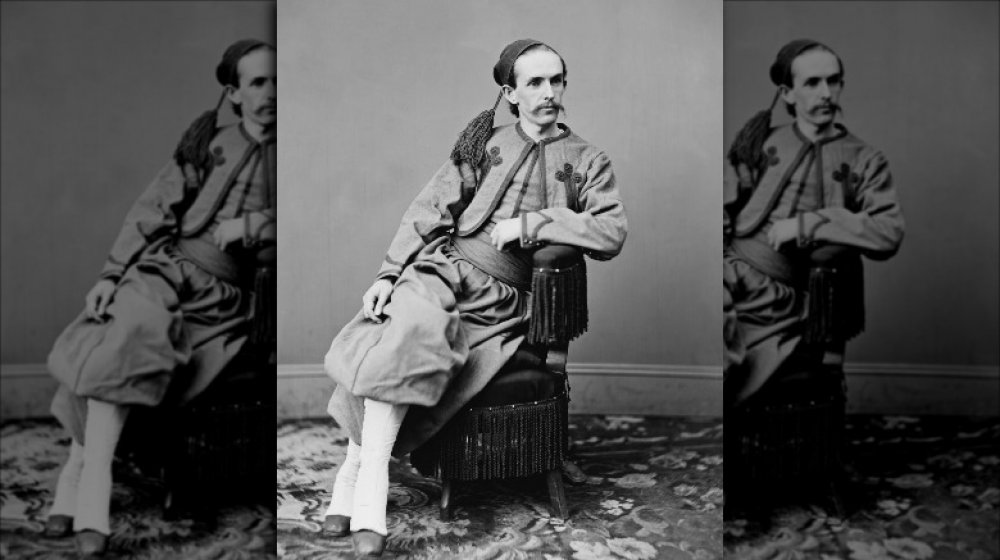

According to The Washington Post, John Harrison Surratt kicked off his career during the Civil War. Born and raised in Maryland as a part of a Catholic, slave-owning family, he took over his father's job as postmaster after his death. It allowed him access into a network of Confederate operatives up and down the coast, and he was often tasked with spreading information about Union troops. When he was caught, he was fired... but he was still free to continue what he was doing.

In 1864, Surratt fell in with John Wilkes Booth and a group of conspirators who were hoping to kidnap Abraham Lincoln, ransom him for the exchange of Confederate prisoners of war, and deliver a brutal blow to the Union. That never happened, though — instead, Booth assassinated Lincoln and fled, with the help of Surratt's mother, Mary.

Surratt was in New York at the time of the assassination, and when he started seeing his name in newspapers, he headed for the Canadian border. He spent months in hiding — while his co-conspirators (including his mother) were tried and hanged. From there, he went on the run: after a wild chase across Europe, he was arrested in Egypt. He did go on trial — which ended in a hung jury. Attempts at re-trying him were thrown out on a technicality, and he was free to go. Ultimately, he ended up getting married, having seven kids, and working for a steamship line.

The spy who escaped because of the top secret information he stole

According to official reports released by the National Security Agency (NSA) (via The Telegraph), a spy named William Weisband was single-handedly responsible for "perhaps the most significant intelligence loss in US history."

What happened was pretty straightforward: Weisband was working for American military intelligence while spying for the Soviet Union, and handed over vital details surrounding America's codebreaking system. Weisband — who had been recruited by the KGB in 1934 — told his Soviet handlers about a program called VERONA, which was used to unmask Soviet spies. After his alert, US intelligence was suddenly no longer able to intercept and decode Soviet communications, both civilian and military.

In turn, those actions were also blamed for the US's complete lack of preparedness for the events that kicked off the Korean War, and here's where things get downright bizarre. In 1950, he was questioned and dismissed by his employer and predecessor of the NSA, the Armed Forces Security Agency. According to The Washington Post, his betrayal caused a massive problem: because the information he'd dealt with was so secret, the evidence against him couldn't be presented in court. He was released, got a job selling insurance, and died in 1967, after having a heart attack on the George Washington Memorial Parkway.

Fleeing the Nazis... and frostbite

Sven Somme didn't start out wanting to be a spy. Before World War II broke out, he was a regular sort of chap, a middle-aged fisheries officer from Norway. When the Nazis turned their hungry eye toward his homeland, though, he wasn't about to stand for that.

Things really kicked off with the execution of his brother, Iacob. He had been captured after helping to sabotage a hydro plant, and by extension, there was a warrant issued for Sven's arrest, too. He remained a free man until 1944. He was taking pictures of German U-boat facilities when, War History Online says, Nazi officers saw the sun reflecting off his camera, and he was apprehended. He waited until the middle of the night, slipped out of his bonds, and strolled away past guards who didn't give him a second glance.

The next two months were long, and Somme led his pursuers — around 900 Nazi soldiers and a regiment of dogs — on a wild chase over 200 miles of harsh, snowy terrain. He plowed through snow, walked through freezing streams, and occasionally scaled pines and jumped from tree to tree to hide his tracks. Fighting frostbite, his life was saved by a family who took him in and gave him new boots. After spending a few weeks in a safehouse, he eventually made it to England where he settled down and lived happily ever after.

From disillusioned student to infamous spy

Throughout the 1930s, the Soviet Union took full advantage of the disillusion of the youth: even as many were protesting against their own establishment, the KGB swooped in to offer them something else. According to NOVA, they successfully recruited around 40 spies from Cambridge University alone — including Harold "Kim" Philby.

And Philby was a complete win for them: he joined the British Secret Intelligence Service, rose through the ranks, and in 1949, he finally transferred to Washington, DC — where he was a liaison between British intelligence, the CIA, and the FBI. Needless to say, he had access to a ton of classified information — and knew when those suspected of being Soviet spies were about to be brought in for questioning. Even after he tipped off several of his fellow spies and allowed them to escape, it would be years before British agents were able to confront him.

In 1963, Philby confessed everything to a British agent named Nicholas Elliott. Elliott, says The Guardian, tried to get him to return to London, but instead, Philby hopped on a freighter bound for the Soviet Union. Philby spent the rest of his life in Moscow and died in 1988 (via The New York Times).

For the Fatherland

Kirkus Reviews says that Julius Silber might have faded into obscurity... had he not written a book about his activities spying for Germany during World War I. When Janet Silver Ghent decided to start researching her distant relative (via The Jewish News), she found a wild story. Silber was born in Germany in 1879, and by 1903, he had moved to New York via South Africa. With World War I on the horizon, he decided he wanted to do something for the Fatherland — so, he headed to England, where he got a job with the British postal service's censorship bureau.

From there, he had a pretty brilliant way of passing any information he happened to learn on to the Germans: he'd pick a name from the list of suspicious people the British had compiled, address an envelope to one of them, seal the letter — and microfilm — inside, then add his own "Passed by the Censor" stamp.

He was never discovered. After the war, he took advantage of a program designed to boost tourism in Belgium, and took off for the mainland. From there, he headed off to Berlin, and at the end of his autobiography — which is the only way we know any of this — he wrote, "At last, I was home." Silber was never captured, and it's unclear what happened to him afterwards. The Jewish ex-spy left Germany with the rise of Hitler, headed to New York, and vanished.

The real-life Americans

In 2013, television audiences were introduced to The Americans, a spy thriller series starring Keri Russell and Matthew Rhys as Soviet spies who had been set up in the States — complete with two children who had no idea who their parents really were. Unlikely to have happened? Not so fast.

Elena Vavilova and Andrei Bezrukov were a real-life Russian couple who temporarily went their separate ways in the 1980s. Each headed to Canada, where they "met" and "married" again, starting their new life together with stolen identities. Now, they were Tracey Foley and Donald Heathfield. The point was to live perfectly normal lives as perfectly normal people — who just happened to have extensive training in weapons, surveillance, and accents. And they pulled it off: when they were arrested, they had two sons, 16 and 20. Neither had any idea their parents — who had been living in Boston — had been sending coded messages back to their handlers.

They were arrested — along with others — in 2010, after the US turned Russia's head of deep-cover operations, Alexander Poteyev, but were given back to Russia in a spy swap. Just what sort of information they reported isn't known, says The Guardian, but Vavilova has written a book and given interviews about her experiences.

They're not just knitting needles, they're knitting needles of freedom

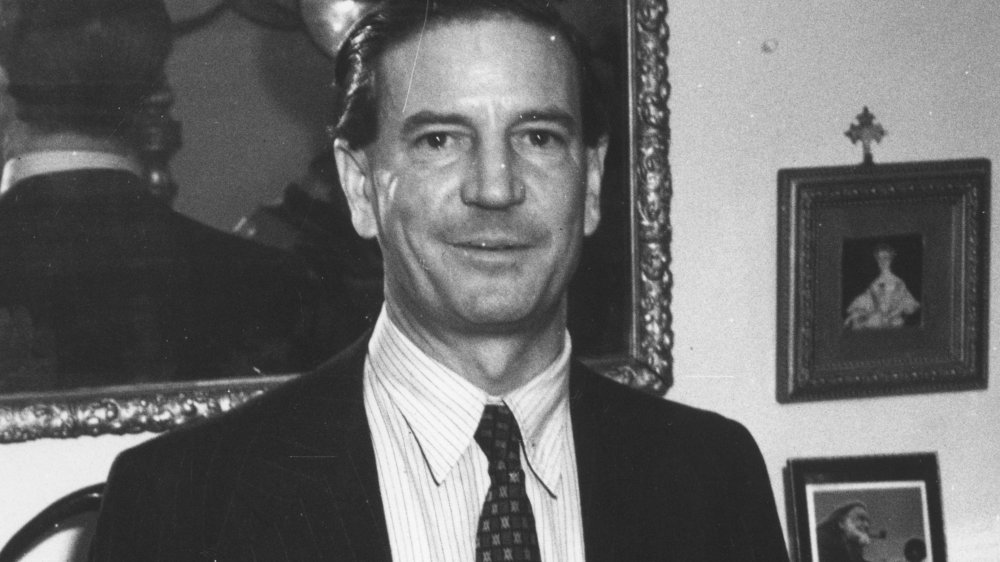

George Blake (pictured, with his mother) was convicted in 1961, and said (via The Guardian): "I must freely admit there was not an official document of any importance to which I had access which was not passed to my Soviet contact." According to the UK's history blog, it started when Blake was captured by North Korea in 1950. When he was released, the MI6 officer kept working for British intelligence... along with Soviet intelligence. Codenamed DIOMID, there was reportedly only one person — his handler — who knew his real identity.

Blake's career as a spy was relatively short-lived, and after his duplicity was discovered, he was arrested, tried, and sentenced. It was 1961, and that's definitely not the end of his story. Just five years into serving his sentence at Wormwood Scrubs, he ended scaling the wall of the prison with a ladder made from knitting needles. With help from fellow — and former — inmates, he arranged to be smuggled out of the UK under the back seat of a camper. For two months, The Guardian says Blake moved from house to house, hiding out with those willing to harbor him, and having a series of close calls.

Still, he made it into East Germany and then on to Russia: in 2016, the 93-year-old was still living in a cabin in the Russian forest with his wife.