What It Was Really Like To Watch The First Space Launches

Nowadays, space tourism is seen as a major possibility, and thoughts of living on a new planet don't seem nearly as far-fetched as they once did. But before we could ever dream of owning a property on the Moon or consider visiting a different part of the galaxy, space exploration had to start somewhere.

The era of the space race, and the years that cushioned it, was as exciting for your everyday person as it was for scientists, cosmonauts, and astronauts. We were finally exploring a world unknown, with no idea of what we'd find. From launching a small satellite that inspired an interior design trend to setting foot on the Moon, these several decades of major space innovation were remarkable, and it's easy to understand how each event went down, even if you weren't there in person.

Thanks to eyewitnesses, the memories from these days still live on. For Sputnik 1, and every launch that followed it, there were memorable moments and unique details that have imprinted themselves in the minds of both everyday people and those who launched and saw space firsthand.

Because of its size, there were few eyewitness to Sputnik's launch

Without the right technology, Sputnik 1 was nearly impossible to see with the naked eye. While some people used sets of binoculars and scientists relied on telescopes and other more high-tech equipment, few viewers could really physically see the launch.

Some who understood how to predict when Sputnik would be within view were able to see a small speck of light moving in the sky. On the other hand, NBC News reported that its carrier rocket was far easier to see. The size of a boxcar, it was much simpler to keep track of the vessel responsible for getting Sputnik to outer space.

The reason why Sputnik couldn't be watched easily was part in thanks to its size. It weighed only 180 pounds and was comprised of a petite silver sphere and several thin antennae, so it makes sense why its small shape was so hard to point out in the sky.

Scientists on the launch site said Sputnik appeared to be falling

Science works in funny ways, and when the atmosphere and perspective get involved, things get even weirder. After Sputnik and its carrier launched, scientists and nearby observers noticed something odd. Although the satellite was supposed to be heading up toward space, it seemed to have taken a turn for the worse. From where people were standing, the contraption now seemed to be barreling back toward Earth, signaling that something went wrong — it was as if it was falling from the sky.

Not only was it jarring, but The Space Review says the image haunted observers because how reminiscent it was of aircraft being shot down in World War II. Fortunately, this bizarre optical illusion could be explained by science, and Sputnik still managed to reach outer space.

The Space Review explains that while the rocket seemed as if it was soaring lower in the sky, it was all because of the mileage it was gathering as it moved further away from observers: "The rocket was not losing altitude, but was concentrating almost entirely on gaining speed." While this may seem like a simple thing observers brushed off, it was so much more. This set the precedent of the entire witness experience when it came to viewing space launches. Scientists and space enthusiasts now knew better about what to expect during these events.

Milt Heflin tuned into the radio to listen to the first-ever space launch

Sputnik 1 officially launched on October 4, 1957. While it was difficult to see with the naked eye, that wasn't the only way to witness it. Folks such as Milt Heflin could tune into the radio to hear its beeps from space. "I can still picture myself sitting in the backyard at a card table, with a battery operated radio ... the beep, beep, beep in the head phones. Man, that was really wild," he told ABC News.

But it wasn't common knowledge to many that the radio was a form of staying in touch with Sputnik. Heflin, who was 14 at the time, mentioned that once members of his town caught wind that he was able to tune into the beeps, he was approached by many asking how they could do the same. Heflin's love of radio eventually led to him serving as a flight director at the Johnson Space Center.

While Sputnik orbited the planet, making its rounds every 96 minutes, listeners were able to tune in for 22 days, admiring its high-pitched beeps until the satellite's battery lost power. Once the American government fully digested that the Soviets had beat them to space, things were kicked into overdrive. The U.S. was now adamant that more money and efforts needed to be funneled into the weapons and space programs. This also helped slowly kick off the space race, and the Soviets rushed into getting more recognition for their aerospace efforts, next with a dog.

Laika the dog witnessed Sputnik 2 firsthand

Following the launch of Sputnik 1, scientists began to step up their efforts for upcoming space missions. The Soviets' Sputnik 2 would send the first animal to orbit the planet, a dog, to see how a living animal would react and adjust to the new environment. While the thought of a dog in space may sound cute or interesting in theory, the story, and Laika's experience, was far grimmer.

Laika was a stray dog found in Russia and actually came in second place in a competition to see which canine would be sent to space. But before the mission took place, they swapped out the winner (who had recently given birth) for Laika. On Nov. 3, 1957, Laika blasted off for space. Although it wasn't expressed to the public, scientists went into the experiment expecting that she wouldn't be coming back down alive. It was claimed that she lived several days after Sputnik 2 landed, but the truth came out eventually.

Laika made it to space, but it was a tragic journey. Scientists recorded the dog's heart rate to be three times its normal resting rate, and only several hours after takeoff, she died of stress and heat exhaustion. BT reports that a team member later revealed that had she survived, the scientists still planned to poison Laika with tainted dog food after her return and subsequent testing. Although extremely controversial, many recognize how powerful and important Laika's contributions were. She helped set expectations and inspire the next rounds of space travel.

Two schoolgirls witnessed Yuri Gagarin's space capsule landing

On April 12, 1961, the first human made it to space. Inside the Vostok 1 rocket was cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin, who braved the first trip orbiting the Earth. While up above, he saw everything from rivers and farmland to the Earth's shape. Despite difficulties with maneuvering the ship and landing, he made it back in one piece, much to the surprise of witnesses.

When Gagarin returned from his mission after 108 minutes of orbit, Baba Lida and her friend, who were schoolgirls at the time, saw the landing of the capsule. She explained that the two of them witnessed the capsule hitting the ground and bouncing. Lida and her peer weren't the only ones to see Gagarin make it back to Earth. It is also said that Gagarin startled a farmer and his granddaughter after approaching them in his spacesuit. According to Smithsonian Magazine, he responded to their fright by saying, "Don't be afraid, I am a Soviet like you, who has descended from space and I must find a telephone to call Moscow!"

Upon his arrival, there was a ceremony two days later in Red Square to celebrate the feat. While the Soviet space team reveled in their accomplishment, it was a different story in the U.S. This accomplishment meant the Soviets had officially beat America to getting a human in space, which immediately kicked off the competition between the two nations to get to the Moon first. But before that happened, several other incredible launches took place.

Alan Shepard admitted things weren't in technicolor during the Freedom 7 launch

A little over three weeks after Gagarin returned, Alan Shepard became the first American to reach space. This was a major accomplishment, not only for Americans but for Shepard himself. Prior to his trip he came down with Meniere's disease, which can cause dizziness, vertigo, and ringing in the ears — unsurprisingly unideal for those who are required to spend time in spinning metal tubes in zero gravity. Thanks to surgery, Shepard was nevertheless able to be the first American man in space.

Shepard's journey was shorter than you might expect. Rather than orbiting the Earth, Shepard made more of an arc, going up into the atmosphere only to come crashing into the ocean 15 minutes later. Despite the fast pace, Shepard's ride was one for the books — even if he bluffed a bit. His takeoff was jarring, and America Space reports that the ride was so shaky that Shepard couldn't read the spacecraft's gauges. This ended up not being the only issue in terms of visibility. Once Shepard could finally see the Earth, he was quoted saying, "What a beautiful view," but it wasn't as dreamy as he first described.

America Space says Shepard later admitted to a fellow astronaut that the view was, in fact, rather dull. Shepard had a gray filter on the windows of his spacecraft to protect his eyes from the Sun, and he didn't manage to remove it in time.

Moscow residents saw the first pictures of Valentina Tereshkova aboard the Vostok 6 on TV

The Soviet Union was able to claim the title for getting the first woman to space, too. Inspired by Yuri Gagarin, and with no pilot experience, Valentina Tereshkova made the trip in the Vostok 6 capsule on June 16, 1963, but she wasn't alone. Two days prior to her leaving, cosmonaut Valeriy Bykovsky went up in Vostok 5. While both were in space, they were able to have a discussion from inside their respective spacecraft. Those who were able to tune into the correct radio signals could also hear the conversations both cosmonauts had with ground control.

Tereshkova spent almost three days in space, and unlike the launch of Sputnik 1, viewers were actually able to see pictures and hear recordings from her on TV. According to the BBC, "Moscow Television broadcast the first pictures of the elated blonde — code-named Seagull — ninety minutes later." Other quirky details were reported, such as Tereshkova complaining about her pen losing ink and the cosmonaut falling asleep during the Monday she was in space. Aside from the scientists on the ground, Tereshkova spoke with someone else, too: Russia's prime minister at the time, Nikita Khrushchev, over the radio while she floated above the planet. The pride the country's leader felt for her was clearly reflected in the public opinion, too. The BBC also reported that large crowds of women flocked to Red Square to honor Tereshkova's launch.

Russell Schweickart became extremely ill during the Apollo 9 mission

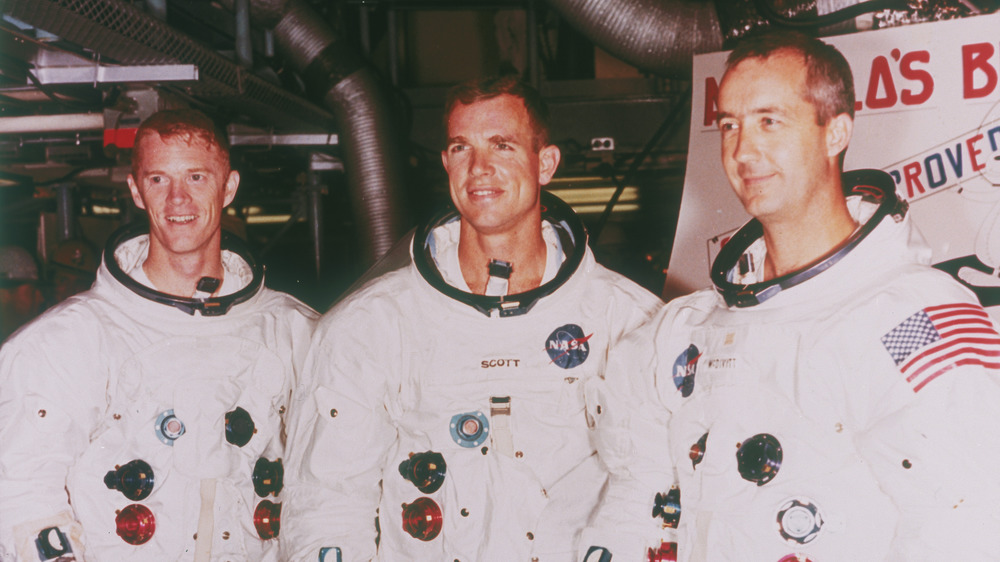

Apollo 9 was a major mission that helped set the stage for the lunar landing and gave NASA a chance to test different space tasks and figure out docking protocols. James McDivitt, David Scott, and Russell Schweickart manned the mission and even managed to snap photographs while they were inside the lunar module, but things didn't go quite as smoothly as they hoped, at least in terms of the team's adjusting to the extraterrestrial environment.

Unfortunately, Schweickart began to really feel the effects outer space has on the body. Air & Space reports that admitting illness as an astronaut was unheard-of back then, as doctors could possibly deem them unfit for space, but within the first few days of liftoff, it was impossible for Schweickart to keep his motion sickness a secret. He was responsible for testing out the life support backpacks the lunar landing crew would be relying heavily on. But if he was ill in his suit while testing, it could easily turn into a life-or-death situation. Thankfully, after a night of rest, he was able to gain his composure and test the packs out.

Some radio listeners complained about astronauts cursing during the Apollo 10 mission

Apollo 10 may not receive the same fame and glory that Apollo 11 did, but it was the flight that paved way for the Moon landing to successfully take place. Aside from testing out controls and seeing what it was like maneuvering the lunar module, the team also managed to test out the path the Moon landing craft would take – making sure the trail set out before them was even possible.

The mission was successful for many reasons, but with every victory comes challenges. Despite the scientific strides they made, complaints were received after the crew lost control of the spacecraft — complaints from the general public. When the lunar module began to spin, Eugene Cernan could be heard saying, "Son of a b*tch," over the radio. This, according to Smithsonian Magazine, led to some religious organizations complaining about the profanity that the public could hear over the radio. But press over a minor slip of the tongue was nothing in comparison to the realization that the Moon landing was now possible.

Photographer John Slack had to invent a different way to photograph Apollo 9, 10, and 11

Mastering the art of photography is one thing, but taking photos of rockets and launches is a whole other beast. Because of the launches' noise and brightness, newspaper photographer John Slack, who was a major figure in capturing these types of events, realized there should be a better way to take images during moments like this. As detailed by Florida Today, he and several engineers were able to come up with a way to take photos that was triggered by sound.

While the method worked for Apollo 9 and 10, there was much more pressure on shooting Apollo 11. Astronauts would be landing on the Moon, and missing the image of the rocket launching into space would be a career nightmare. Slack picked a spot to set up the cameras and hoped for the best. Slack recalled to Florida Today, "I did not sleep the night before. I remember they brought the cameras back in a van. The first thing we look for is the counter. The counter showed that all the cameras had fired. We set up four, but we still did not know what was on the film, if anything." Fortunately, a jubilant photo editor told him he had captured the image.

Sandi Olson was glued to the TV for the Apollo 11 launch

The Moon landing was a huge deal, and thanks to the timing, technology was a bit further along. Many people, like Sandi Olson, along with nearly 600 million others, were able to watch in awe on television.

Olson told the Marin Independent Journal, "There's nothing I've seen like it in my life. It's hard to even explain it. It was what I call 'the good old days,' because the whole town, that whole area, just all rallied around these astronauts." After witnessing the launch from the beach, Olson joined other citizens in seeing the astronauts explore from the small screen. She remembered, "I don't think we ever turned the TV off." The world held its breath while Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong did everything from walk around to chat on the phone with president Nixon. Upon their return to Earth, they head to quarantine for a bit over two weeks for fear of any diseases they could've picked up in space, according to History.

Jay Barbree slept in his broadcast booth for two days

Everyone knows what it's like to have a long day at the office, but no one understands this quite like journalist Jay Barbree. Responsible for covering the Moon landing, the reporter slept for only a handful of hours each day during the mission and stayed overnight in his booth during the event. Not only that, but Barbree also camped outside of the space center before reporting on the Moon landing. Talk about dedication to your job.

At one point, he and other reporters stepped out for dinner, which Barbree wasn't too happy about, fearing missing out on the astronauts taking their first steps. His intuition ended up being correct. He told Florida Today, "I tried to tell the NBC guys it may not last that long. They hadn't even brought our food and then they call and say 'They're going out early. Get back here!' So we had to take off and run back. And I said, 'I told you!'" Luckily, the reporters made it to the booth and got to watch Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin take the first lunar steps along with the rest of the world.