What Was It Really Like Pioneering The Oregon Trail?

When most people think about the Oregon Trail, they typically dwell on two things. First, if you are a Gen-X'er, a cheesy but highly popular game for the PC. Second, the messed up stuff that happened on the trail ranging from murder to snake oil remedies. The truth is that while messed up stuff certainly happened on the Oregon Trail, for most pioneers who traveled it, it was a slog that had moments of death, romance, lots of monotony, and stunning scenery.

The Oregon Encyclopedia says that between 1840 and 1860, up to 400,000 people, sometimes called "overlanders" or "emigrants," transversed the over 2,000-mile path to reach the Willamette Valley in Oregon or to locations in California and Utah. The trail, which the National Park Service states was considered to begin at the towns of St. Joseph or Independence, Mo., was unpaved, rough, and wild. Settlers usually left from Missouri in early April in order to arrive in the West before winter. At a rate of between 12 to 15 miles a day, the entire migration of these overlanders could take to up to half a year.

How did they do it?

They used wagons but rarely rode in them

Pioneers who journeyed on the Oregon Trail used wagons. According to the National Oregon/California Trail Center, pioneer wagons had to be light but durable enough to take a beating. Most settlers used converted farm wagons, while others relied on ones specially made for the Oregon Trail. A common misconception is that overlanders used Conestoga wagons — they did not. According to the National Oregon/California Trail Center, those famous wagons were used for freight on other trails.

According to the Oregon Encyclopedia, the wagons weighed up to 1,400 pounds and hauled nearly a ton and a half. Because of the strain, trail wagons were usually mostly made of hardwoods such oak, hickory, and maple. The wagon bed, at only 4 feet by 10 feet, was crammed with supplies. If the wagon broke down on the trail, it could be an arduous if not impossible process to fix it. According to the National Oregon/California Trail Center, the tires, axles, and the connections in the undercarriage took the most abuse. These parts were reinforced by iron. The whole ensemble was covered up with white canvas held by hoops which led some, according to Britannica, to call the pioneer wagons prairie schooners.

Prairie schooners gave an uncomfortable ride. There were no springs or suspension systems to cushion the jolts of 2,000 miles of rocky wilderness. Most overlanders, therefore, walked, not just because of the lack of comfort but because the wagon was full of stuff.

Safety in numbers

Because the Oregon Trail was so long and so full of unknown hazards, pioneers organized themselves into larger caravans called wagon trains. According to the Bureau of Land Management, this created a mobile community that had the virtue of protection in numbers. The pioneers were also well-structured. Wagon trains operated through, according to the Oregon Encyclopedia, written agreements that dictated rules of who does what and designated officers to the caravan. Such contracts were used until about 1850, when they were replaced by more informal agreements.

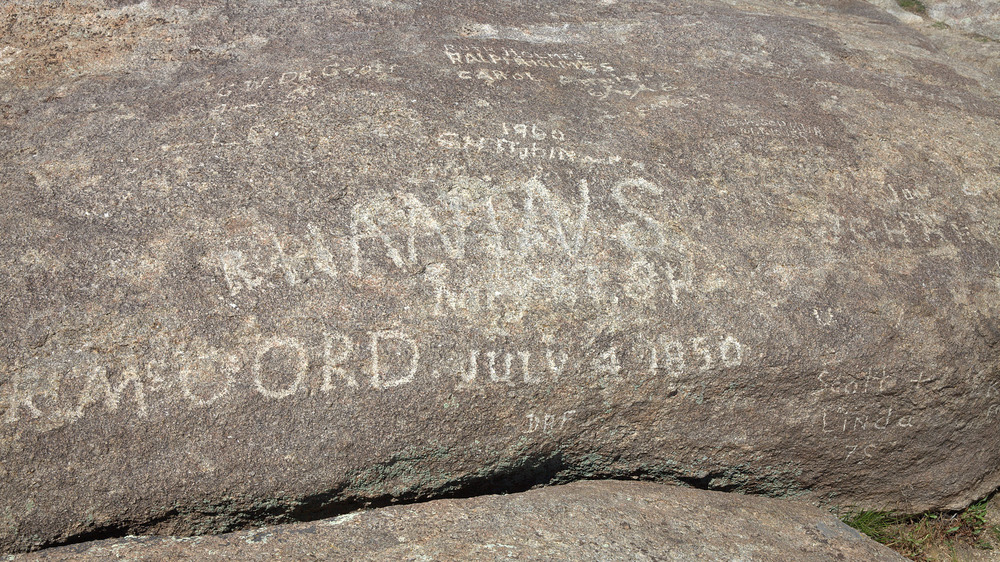

All these wagons had a direct impact on the environment. Smithsonian Magazine reports that to this day, ruts from Oregon Trail wagon trains are still visible. In fact, the trail was modified over time as pioneers discovered shortcuts. Overlanders even carved graffiti into stone, with one prominent example being Independence Rock in Casper, Wyo., which was dubbed one of the "registers of the desert."

Only three sets of clothes for six months

Oregon Trail pioneers needed a considerable amount of equipment in order to survive the months-long journey. According to the Bureau of Land Management, not only did they need basic tools to repair broken wagons but also rifles to hunt game, bedding, tents, and cooking equipment. Pioneers usually only had up to three sets of clothes made of wool or linen that had to last through the entire journey. According to an Iowa State University thesis on the subject, there are actually few surviving examples of Oregon Trail dress, since the clothes were so worn out by the time the pioneers reached the trails end they were either recycled or discarded.

Discarded, too, were those items which were found to be impractically too heavy for the trail. As the animals hauling the wagons grew increasingly tired, the pioneers were forced to get rid of all things not essential. The trail was strewn with furniture, trunks, beds, cast iron stoves, and other personal belongings. The trail probably did not lack reading literature since books also were thrown away. What was most essential for the pioneers was to have a large stockpile of food.

The Oregon Trail ultra-diet plan

When you walk for 2,000 miles you are going to burn lots of calories. Outside Magazine has provided a calculator which shows that a hiker without a pack walking 4 miles per hour on level ground path burns 106 calories per mile. In this best of circumstances, it may be assumed that an Oregon Trail pioneer walking 15 miles a day was expending about 1,600 calories a day at minimum. This is a very low estimate, since a pioneer would be dealing with rugged terrain. To fuel their bodies, the settlers needed lots of food.

The National Oregon/California Trail Center shows that the Oregon Trail pioneers did not eat healthy food but ate food that could last for months. It is estimated that a family of four required 400 pounds of bacon, 600 pounds of flour, 100 pounds of sugar, and 200 pounds of lard. They also often brought dried peaches and apples, as well as sacks of rice. To wash it all down, they carried 60 pounds of coffee and four pounds of tea. The Job Carr Cabin Museum adds cornmeal, butter, vinegar, salt, and baking soda to the larder. And of course there was whiskey or brandy — for medicinal purposes.

On the journey, overlanders would supplement their meals through hunting and fishing. A larger family often required more food, which could exceed the recommended carrying load of the wagon. Some families had to bring two wagons with them. Others brought their own livestock, like cows, for dairy products.

Ox or mule?

One of the most important choices an Oregon Trail pioneer had to make was what animals to bring. Probably the most critical choice was selecting which draft animals to haul the wagon. An article in the Great Plains Quarterly notes that this choice boiled down to either mules or oxen.

Oxen were sometimes preferred since they were able to live off of the wild pasturage. Some overlanders believed that these animals would not wander off, and Native Americans were uninterested in them, so there was no threat of theft. The same was true for mules. However, according to the National Oregon/California Trail Center, mules had the virtue of speed, but they were harder to handle than oxen. Oxen were also cheaper than mules. Overlanders often waited until they reached a departure point to purchase their supplies and draft animals so that they were in the freshest condition. It was also cheaper to buy the animals in, say, Independence rather than back east.

Many of these animals never finished the journey. After a few weeks of hauling heavily laden wagons, the animals would flag, and many would either refuse to go any further or simply collapse and die. The pioneers would see dead animals on the trail every day. Sometimes the bodies could be eaten, or sometimes the meat was sold. When animals did perish, the emigrants often were forced to buy replacements for stiff prices at the far flung trading posts and forts along the trail.

Native American attacks were overstated

One of the great myths of the Oregon Trail that is finally being thoroughly debunked is that Native American tribes were a menace to the pioneers. The truth is that the relationships between the emigrants and Native Americans was more complex. According the Bureau of Land Management, the pioneers were passing through the lands of a number of tribes with complex societies, including the Sioux, Cheyenne, Comanche, and Arapaho. The white pioneers were generally filled with paranoia about Native American attacks, and it is that paranoia that has carried down in popular memory.

The Native Americans generally viewed the white travelers as potential trading partners. They would supply the settlers with food in exchange for tools, firearms, and small trade goods like mirrors and metal tools. Overlanders hired Native Americans to herd their livestock, assist in crossing rivers, and help guide them along the trail.

Rinker Buck, author of The Oregon Trail: A New American Journey, in an interview with National Geographic, stated, "They bartered with immigrants for trinkets, supplies and horses. They were very helpful at first. In fact, the ingenuity of the Indians in crossing the rivers was a crucial aspect of the Oregon Trail. You have to ford numerous rivers, and the Shoshones, Pawnees and Sioux, were extremely adept at helping the pioneers make these fords."

Deteriorating relations on the Oregon Trail

As time went by, the relations between the pioneers and Native Americans grew worse. The emigrants never got over their paranoia and frequently shot at peaceful Native Americans, according to the Oregon/California Trails Association. Rinker Buck noted to National Geographic, "For about 20 years it was very friendly as opposed to the impression that you get from Hollywood movies. But when the Indians realized the White Man was there to slaughter the buffalo, their protein source — and we did, in hellacious numbers — they turned hostile and declared war." Most of the attacks on the Oregon Trail occurred near the Snake and Humboldt rivers or near the southern end of the Willamette Valley to the Applegate Trail, according to the Oregon Trail Center.

Still, casualties were low. John Unruh calculates in his book, The Plains Across, that between 1840 and 1860, 362 pioneers were killed by Native American attack and 426 Native Americans were killed by pioneers, with most of the deaths occurring in the latter years. Keep in mind that Native Americans were far more impacted by the diseases brought by settlers and their impact to the environment.

Frankly the pioneers should have been worried about other possible causes of death.

The Nation's longest graveyard

Even though the threat of violence from Native Americans was exceedingly minimal, the Oregon Trail was still highly dangerous. The National Parks Service reports that the mortality rate of the pioneers may have been up to 10%. The causes of death were numerous. Pioneers brought firearms with them for hunting and sport, and accidents through inept handling frequently occurred. One pioneer wrote, as reported by the Baltimore Sun, "I confess to more fear from careless handling of firearms than from an external foe." Other major accidents included drownings, and being run over by wagon wheels, or by the animals they brought. Harsh weather also played a factor, which included lightning strike.

Yet the biggest killer was disease. Pioneers suffered from measles, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and dysentery. These diseases were dwarfed, however, by cholera, which was the chief killer on the Oregon Trail. Cholera, which is caused by a bacteria in tainted water, causes abdominal pain, diarrhea, vomiting, and death. A person may die within 12 hours of the onset of symptoms. Overlander Cecelia Adams wrote in her 1852 diary, as quoted by the Baltimore Sun, "Passed 7 new-made graves, One had 4 bodies in it — cholera. A man died with the cholera ahead of us." The worst outbreaks of cholera occurred, according to a thesis from Portland State University, between 1849 and 1852.

Estimates vary, but disease alone may have claimed up to 30,000 pioneers.

Pioneers brought their kids on the Oregon Trail

Children shared the dangers of the Oregon Trail with their parents. The Bureau of Land Management estimates that 40,000 of the pioneers were children. Children on the trail took part in the same chores and duties as adults. Oregon/California Trails Association says that one family with nine children only permitted the 3 and 5 year olds to escape work. Such chores may be to help bake food, assist driving the wagon, or minding any of the loose livestock the settlers brought. There was no formal schooling on the trail except for what the family could tutor them.

Children brought with them vivaciousness, which enlivened the camp. At night they played games like leap frog and London Bridge, as well as song and dance. One such account, as recorded by the Oregon/California Trails Association, states that a boy named Robert got his hands on a pair of Spanish spurs. He put these on and then attempted to ride one of the tempestuous mules. One of the party reported, "he looked so ridiculous flying over the mule's head. We heard no more of Spanish spurs."

Children often were seriously injured and died in accidents on the Oregon Trail. Such cases included a wagon wheel rolling over a child, breaking limbs or outright killing them. An 1849 diary entry records, "A lady and four children were drowned through the carelesness [sic] of those in charge of the ferry."

A typical day on the Oregon Trail

As the emigrants crossed North America, each wagon train fell into a routine. According to the Oregon Trail Center, a typical day began at 4 a.m. to the sound of a bugle or rifle to wake up the caravan. At 5 a.m. the livestock that was let loose to graze overnight were rounded up after which breakfast was served. By 7 a.m. the evening camp was packed and wagons hitched. At a sound of a trumpet and a call "Wagon's ho!", the caravan proceeded with men riding ahead on horses to scout the path.

At noon, the wagon train halted for a rest and a meal. At one, the caravan was on the way again, generally proceeding until about 5 p.m. when camp was made by circling the wagons as a corral, followed by suppers, daily tasks, and some leisure time. Typically the camp turned in at 8 p.m., and a guard was set who was relieved at midnight. The process would then repeat itself at 4 a.m., with the exception of some wagon trains that halted for extended periods or for the entire day on Sundays for religious observances.

Are we there yet? ... Not yet.

With a journey so long and mainly monotonous, Oregon Trail pioneers adopted routines and even a semblance of what settled life was like. According to the Oregon/California Trails Association, there were a number of marriages and births on the trail. Most weddings occurred at the debarkation points in the east. Romance also bloomed on the road, and couples married. The newly wed couples were often subject to a charivari (pronounced shivaree), which was a joking custom supposed to prevent the consummation of the marriage. This might entail banging pots and pans and dragging the newlyweds out into a drunken mock parade, as per the History Collection.

With a journey so long, tempers frayed. According to Rinker Buck in his interview with National Geographic, as pioneers moved further, tempers flared. Fights would break out, especially during river crossings in which people's livestock and possessions would get mixed up. Buck said, "People would pull their guns out and start shooting each other. I feel that the Oregon Trail years and the stresses and the tensions of the crossing introduced this kind of violence into the American ethos."

Perhaps the pioneer Loren Hastings summed up the Oregon Trail experience best when she later told the Oregon Pioneer Association, "I look back upon the long, dangerous and precarious emigrant road with a degree of romance and pleasure; but to others it is the graveyard of their friends."

A strange incident on the Oregon Trail

With the pioneers under such an enormous amount of stress, strange things happened. It is worth noting one incident, as written about by Tricia Martineau Wagner in It Happened on the Oregon Trail, which demonstrates how the Oregon Trail could result in extreme psychological trauma. In 1847, Elizabeth Markham, a pregnant pioneer, worn out by the trail, refused to go a step further in the vicinity of the Snake River. After her husband, Samuel, and fellow emigrants could not convince her to move, they left her on the trail. However, further along the trail, Samuel sent his 15-year old to find her.

While he was gone, Elizabeth returned of her own accord. Samuel asked if Elizabeth had seen their son. She replied, "Yes, I picked up a stone and knocked out his brains." Samuel Markham ran off to find his son. While he was gone, Elizabeth set fire to their wagon, which other members of the wagon train struggled to put out. When Samuel returned with their son (whose brains had not been bashed out), he found almost all of their supplies destroyed. Apparently, the Markhams completed their journey, and the Elizabeth gave birth to Columbia, named after the Columbia River.