The Crazy True Story Of America's Stunt Girl Reporters

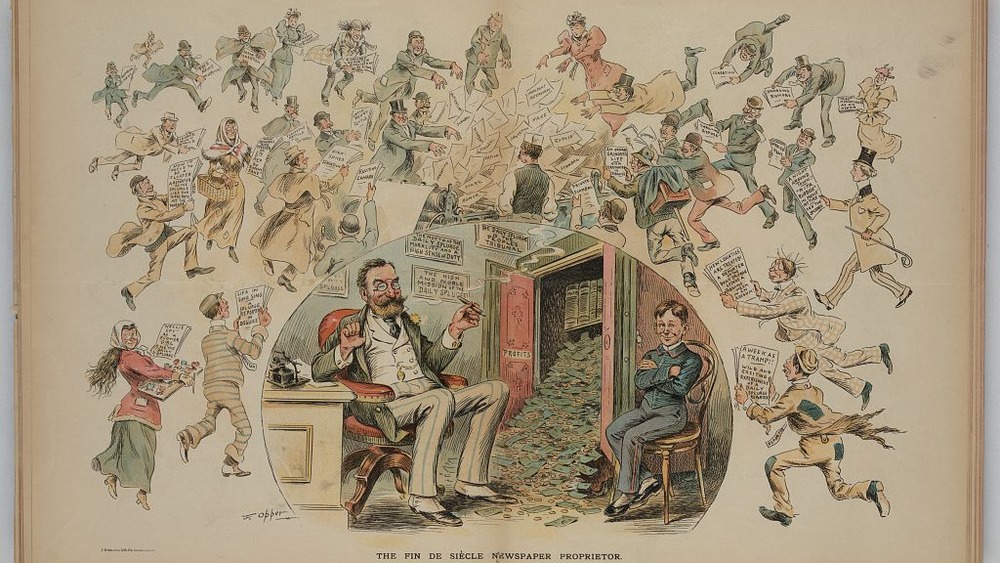

Believe it or not, there once was a time when journalists were celebrities. It wasn't just talking heads on TV or social media influencers, either — these were real investigative journalists risking life and limb to bring you the unvarnished truth about everything from slum life to factory work. In the late 1800s through the 1920s, there was no radio or television — your social media chatter consisted of what you overheard at the store or, if you were rich, at dinner parties. So newspapers were the main way of getting information — and newspaper publishers wanted to sell as many copies as possible.

Weirdly, that created an overlap with the kind of intrepid investigative reporting that doesn't often get financed these days. Exposes and shock-value articles sold papers, and publishers loved it — so they often funded both detailed undercover work and gimmicky stunts that caught readers' attention. And, just to help boost the eyebrow-lifting quotient in an era when women were expected to stay home and stay quiet, those newspaper publishers often hired female reporters to get to the bottom of the next big scandal.

What was a "stunt girl" reporter?

At the turn of the 20th century, conditions for many were...not good. The Industrial Revolution had made sweeping changes in how society lived and worked, and often these weren't great for the people laboring in the new factories. Child labor was normal (and really, really awful). Plus, there were all kinds of rules and laws that basically made anyone who wasn't a rich, straight, white male automatically sub-human – with few rights and little way to change their situation.

It was against this backdrop that a genre of intrepid female reporter emerged, ready to go undercover and report back, in painful detail, about how people lived in slums, asylums, factory towns, and beyond. According to Smithsonian Magazine, this battalion of female reporters risked reputation, life, and limb to bring awareness of the subhuman conditions of many of their fellow citizens into the minds of society's movers and shakers. Unable to ignore the shocking revelations– or the public backlash against the newly revealed injustices — the upper echelons began to implement reforms to better everyone's condition.

Granted, these brave, skilled journalists were often slighted even in their own newspapers. They were called "girl reporters" and derided by other journalists for supposedly manipulating headline-grabbing situations at best and accused of completely fabricating their stories at worst, as Randall Sumpter writes in American Journalism.

Nevertheless, their work graced the pages of well-known newspapers, both "penny dreadfuls" and legit news organizations, worldwide and would help change the world.

Female stunt reporters entertained and inspired

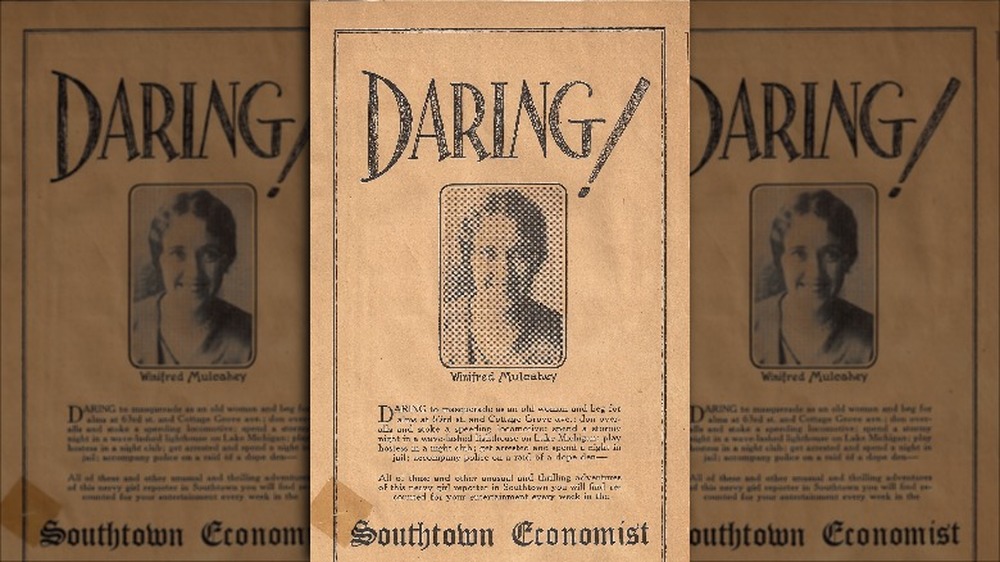

Stunt reporting ranged from tackling various challenges — like training with firefighters — to serious investigations. Women were at the forefront of the movement, though there aren't many biographies of them today. Twin Cities PBS notes that journalists like Winifred Mulcahey and Eleanor Stackhouse Atkinson made waves for their reporting. Meanwhile, stunt artists like Alice Ramsey accomplished feats even men of the time quaked at, like driving cross-country in the early days of the automobile, as Boston.com highlights.

Of course, any reporting beyond dry facts was considered suspect by "serious" journalists — and by anyone who felt threatened either by what was being reported, how it was being reported, or the fact that anyone was entertained while gaining insight. Newspaper publishers themselves accused other papers of making stuff up to sell copies, and the fact that stunt journalism was both lucrative, informative, and entertaining put it in the crosshairs. As the Encyclopedia Britannica points out, the term "yellow journalism," referring to any kind of reporting with sensational headlines, was the product of an ongoing feud between two of the richest men in America, who happened to own newspapers.

Accusations of promoting "fake news," as noted by JSTOR Daily, and especially anything written by a woman seeking to uncover social inequality, was practically a hobby. Yet not even professional slander could stop the female investigative reporters of the turn of the century from getting their scoops...and thrilling tens of thousands of readers.

Who were the names behind many of the greatest girl reporters?

Because their jobs were so dangerous, society was so stratified, and their ability to go unnoticed was key to their work, many girl reporters used pseudonyms. As Smithsonian Magazine highlights, although some have come forward over the years, the real identities of many are unknown — and therefore can't be celebrated them as they should. There are a few collections of undercover work from the turn of the century, like that at NYU, that help document the articles, but too often, little is known about the writers themselves.

For some women, like Winifred Mulcahey of Chicago, there's some information, plus an archive of her writing. One blog reproduces some of her greatest stunt coverage, like training with Chicago firefighters in the 1920s. NYU, meanwhile, has an archive of the dispatches of Catherine Brody, who chronicled looking for work in cities across America. For too many of these skilled writers, though, their true identities have been lost to time and secrecy. As Jean Marie Lutes points out in American Quarterly, using pseudonyms was only sensible for many of these reporters, and newspaper publishers loved the idea of seeming to have a stable of reporters with eyes and ears everywhere, so they often gave a single "girl reporter" multiple bylines.

Yet despite their general anonymity, there are stories of a number of particularly fierce female reporters who would stop at nothing to get their scoops.

Nellie Bly, godmother of undercover reporting

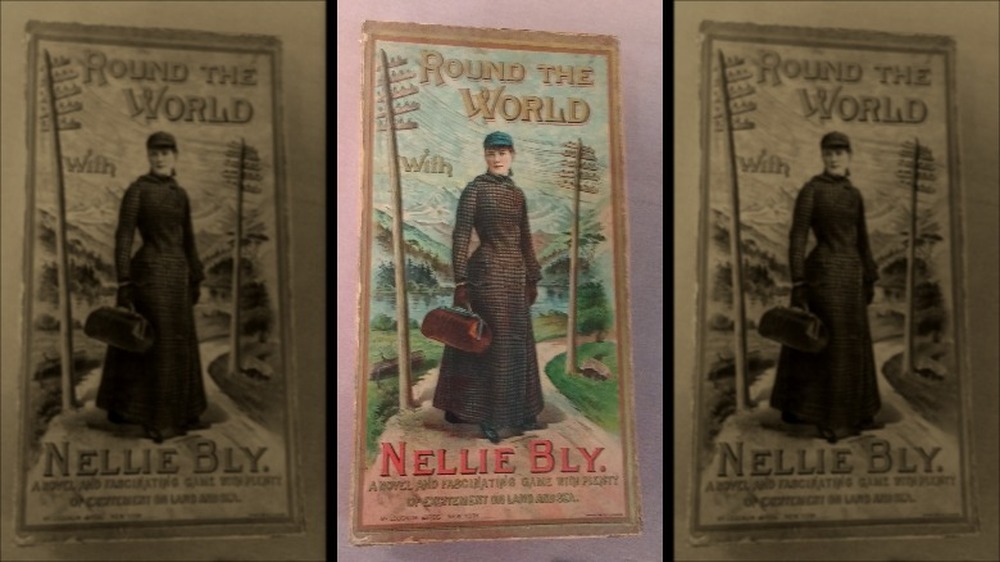

The best-known of the so-called "stunt girl reporters" at the turn of the century was surely Nellie Bly. In the 1880s, Bly dove straight into the deep end of reporting, exposing the truth of life in slums throughout the United States and Mexico. She later turned to ever-more-risky stunts, followed by a voracious audience.

Born Elizabeth Cochrane in Pennsylvania in 1864, as the Encyclopedia Britannica relates, this enterprising and adventurous young woman went to work at the Pittsburgh Dispatch in 1885 after furiously disputing the newspaper's claim that women weren't good for anything except cooking dinner and making babies. She backed up her angry letter with some dang good journalism. Rather than writing about recipes and female-focused fluff, Cochrane took advantage of her new pseudonym, Nellie Bly, to go undercover and write about social inequality in Pittsburgh, as History Extra notes.

When advertisers complained about the progressive content, Bly was moved to the women's pages...which she refused to write for, instead managing to finagle a correspondent position in Mexico, according to History. She reported on the conditions in rural Mexico for nearly six months before attracting too much negative attention for her political exposes and making a hasty return to the U.S. to avoid getting thrown in jail. Still, she got a book out of the process and opened up conversation about Mexico's dictatorial policies at the time.

Nellie Bly went undercover at an insane asylum

Back in Pittsburgh, Nellie Bly was once again relegated to the women's pages. But there was no way she was gonna stay small — or stop reporting on the biggest social issues of the Gilded Age. In 1887, at the tender age of 21 and just two years after starting her journalism career, Bly headed for New York, leaving a note that read, "I am off for New York. Look out for me — BLY," according to History.

They didn't have to look hard. Bly's first gig in New York after leaving Pittsburgh was to get herself committed to an insane asylum in order to demonstrate the indignities — and sometimes outright atrocities — perpetrated on the "inmates," as they were called at the time. She had originally pitched an expose on the treatment of European immigrants in steerage class, but her new editor at Joseph Pulitzer's New York World assigned her to the Blackwell Island asylum instead, as Jean Marie Lutes notes in American Quarterly.

History gives an overview of the horrifying treatment she received after getting herself committed for paranoid delusions, from ice-cold baths to being stripped and taunted by nurses. Bly herself would go into lurid detail about the subhuman treatment in an 1877 book, Ten Days in a Mad-House.

The expose made Bly's career, instantly transforming her into a celebrity and launching a full investigation of practices at the asylum — and other institutions across America, as Encyclopedia Britannica relates.

Nellie Bly beat a fictional record for circumnavigating the globe

Nellie Bly's audience wanted more, and she was happy to oblige. She investigated marriage brokers, the underground baby trade, and massive political bribery — check out the Undercover Reporting archives at NYU for her exploits.

Eventually, Bly was making the news, not just reporting it — and her publisher wanted to capitalize on her fame. So in 1889, the World sent her on a pure stunt assignment — to travel around the world in less time than it took in Jules Verne's Around the World in 80 Days. As the Heinz History Center reports, Bly immediately applied her usual hustle.

What's more, she won that race against a surprise competitor — a Cosmopolitan writer named Elizabeth Bisland, who set out in the opposite direction on the same day, as Smithsonian Magazine relates. Of course, Bly had expected competition — just not from another girl. As History Extra relates, her editor had originally balked at sending her alone, saying only a man or a team could make it. Bly responded bluntly, "Very well. Start the man and I'll start the same day for some other newspaper and beat him."

By ship, train, and automobile, as well as elephants, bicycles, and whatever she could find, Bly and her single small suitcase covered more than 25,000 miles in only 72 days. She soon retired from stunts and married, but would continue writing for the rest of her life until passing away in 1922.

Winifred Sweet Black snuck into disaster zones

Never tell Winifred Black you won't agree to an interview. She'll hide in your train car under your table and join you at dinner, whether you like it or not.

And yes, she actually did this to President Benjamin Harrison in 1892, as Encyclopedia.com relates. But this was far from Black's first rodeo. Writing for the San Francisco Examiner as Annie Laurie, as the Encyclopedia Britannica notes, her first big scoop involved throwing herself under a truck to investigate poor treatment at the city's hospitals for the poor. Black was all about improving health care for society's most vulnerable populations — she risked her life to tell the story of one of Hawaii's leper colonies, as the San Francisco Chronicle relates.

Later, Black would take on a dual role as aid worker and undercover reporter, disguising herself as a boy to sneak inside disaster zones like the Galveston flood of 1900 and the San Francisco earthquake of 1906, as Encyclopedia Britannica details. She'd use those skills on the front lines of World War I as well, reporting on battles and becoming one of only eight women to report on the signing of the Treaty of Versailles, as the blog American Women in WWI details. She kept on writing, covering everything from sensationalist murder trials to political campaigns, until her death in 1936.

Eva McDonald Valesh fought against horrible labor practices

Conditions for workers in the late 1800s were awful — you were lucky if you came home at the end of a 15-hour workday with your fingers intact. And things were worse for women, who were paid less, given fewer benefits, and had to do all the housework, too. One ardent reformer was Eva McDonald Valesh, who went undercover at factories throughout Minnesota to document their bad labor practices. Valesh had herself been a child laborer in a print shop, as MNopedia details. When she moved into the newsroom, she went undercover at a local garment factory and helped the women there organize their first strike just weeks after publishing her expose as "Eva Gay" in the St Paul Globe in 1888.

She'd cover social inequalities in Minnesota's Twin Cities before doing similar work in Europe, reporting back for various U.S. papers, according to Social History Portal. She would also be one of the few women to report on the explosion of the USS Maine in Cuba in 1898, assigned by William Randolph Hearst for his New York Journal.

The National Park Service notes that Valesh built a career as a public speaker and labor activist. Social History Portal recounts that she was a member of the Democratic National Committee before women could vote and advised presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan on labor issues.

She worked as a proofreader for the New York Times for decades, passing away in 1956 at 90.

Elizabeth Banks introduced muckraking journalism to the U.K.

Though her reporting work was widely considered thorough, groundbreaking, and important, little details like date of birth didn't matter much to girl journalist Elizabeth Banks. As Canterbury Christ Church University points out, she was likely born in 1865 but gave her birth year as 1870 on everything from interviews to her passport application. Clearly, this was a woman who knew the value of a good story — including making herself look younger and therefore spunkier in the eyes of her devoted readership.

When she moved to England in the 1890s after a stint as the secretary to the American ambassador to Peru, according to the Women's Who's Who of America, Banks had absolutely no intention of being just another society girl. She quickly started going undercover to expose the plight of London's poor and gained a reputation for being a master of disguise. The University of British Columbia Press notes her long career as a columnist for some of London's most popular newspapers, where she wrote as "Mary Mortimer Maxwell" or "Enid" and frequently defended the rights of suffragettes. She later wrote about her exploits and the realities of being an American woman in England in a series of books, the most famous of which was her autobiography, The Remaking of an American.

Catherine Hay Thompson, Australia's undercover health reformer

Stunt journalism wasn't just limited to the U.S. In Australia, Catherine Hay Thompson, a dedicated educator and social activist, went undercover to investigate asylum conditions a full year before Nellie Bly made her own asylum stay in New York.

A teacher with a top university education, according to AustLit, Thompson landed a job as an assistant nurse at Melbourne Hospital in 1886, planning to write about conditions at the notoriously mismanaged hospital for The Argus, as the Conversation reports. From there, she headed to the Kew Asylum as a nurse, documenting terrible conditions for both inmates and assistant nurses in "The Female Side of Kew Asylum."

Weekend Notes points out that she leveraged her fame as a reporter to agitate for improvements throughout the health care system, improving nursing training as a way to raise standards for workers and patients alike. For 20 years, she reported on the bleak realities of turn-of-the-century urban life, even going undercover at local brothels to expose "all the things happened that you wanted out of sight."

Always a fierce force for change, Thompson would in 1889 become a co-founder of The Sun, a "crusading feminist journal" based in Melbourne, as detailed by AustLit. Her 1932 obituary hailed her as a "pioneer reformer" who represented Australia's women both at home and abroad.

Female stunt journalists left an amazing legacy

Though their more headline-grabbing antics may have been looked down on by politicians and so-called serious journalists, and though there are questions about how much they reported versus how much they made up in search of a sensational story, as the Columbia Journalism Review points out, there's no question that muckraking female journalists at the turn of the century made waves.

And those waves have had ripples well into our era. As Randall Sumpter points out in American Journalism, by exposing cruel treatment in asylums, unfair laws and regulations that punished women for the flimsiest of reasons (like speaking their own mind, le gasp), and workplace flaws that could kill, these brave and pioneering ladies set the tone for decades of progressive reform. The eight-hour workday is partially thanks to the exposes published by Eva Valesh, as Workday Minnesota highlights, and the legacy of Nellie Bly and Catherine Hay Thompson surely improved the treatment of mental illnesses the world over.

Courage, determination, and a willingness to go where no one else bothered to tread — these were the hallmarks of so-called "girl" reporters at the turn of the century. Clearly, there's nothing like a little condescension to fire up women to get stuff done.