The Untold Truth Of Japan's Kamikaze Pilots

When it comes to the Pacific front of World War II — the fight between the Allied forces and Japan — it's not all that hard to end up thinking of the Kamikaze pilots. You know, the Japanese pilots who would dive bomb their planes into Allied ships on insane suicide missions.

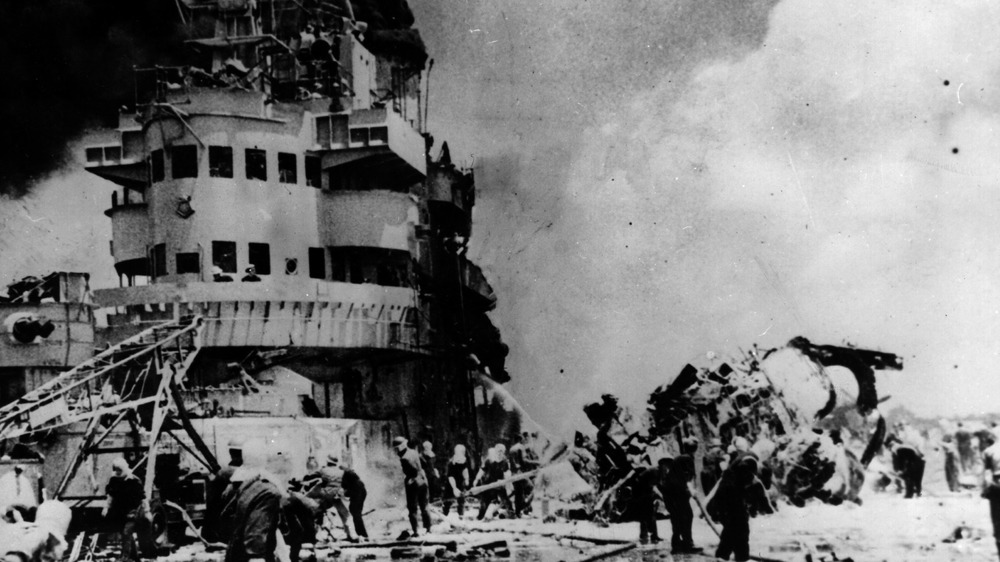

The exact stats around these missions are sort of hazy, to put it blatantly. Best people can tell, somewhere between 3,000-4,000 pilots were involved in these missions, crashing their planes into Allied vessels. That was probably a bit over 2,000 planes that actually took off, with only a fraction of them hitting their targets, sinking somewhere between 50 and a 100 ships but damaging a few hundred more.

And in the time since World War II, the Kamikaze pilots have been portrayed in various different ways, some positive and some negative. But it's not as easy as saying one of those portrayals is exactly right or exactly wrong. The reality is a little more complicated than that. The story as it's widely known is simplified, and the truth is quite a bit more complicated and tragic at the same time.

Japan was losing the war

By the last few years of World War II, things weren't going Japan's way. CMH Online says that the Japanese military was wildly outmatched compared to the Allied forces. Their air force wasn't what it used to be, and they'd lost a lot of their skilled pilots over the course of the war. Combined with the higher quality training and funding given to American pilots, and the more powerful aircraft used by the Allied forces, Japan knew they couldn't keep up. It didn't take long for those disparities to really rear their ugly head. According to an interview with former pilot Atsushi Takatsuka, the Japanese military was losing more and more battles.

Military leaders started increasing their recruitment, drafting university students into the war who had previously been exempt (via Kamikaze Images), but it wasn't enough. Discussions began around fall 1943 about new tactics, but when Japan couldn't stop the Allied forces' march across the Pacific in 1944, they had to do something.

Enter the Tokkotai (or "special attack" units). These were the units intended to carry out suicide missions, and it just showed how desperate the situation truly was. The Japanese military was trying to overcome their handicaps at any and all cost, landing on one last effective defense against the Allies, which they would use through to the last stages of the war.

Kamikaze pilots weren't the only suicide attackers

The Kamikaze pilots became one of the more recognizable units of the Japanese military, but their suicide tactic wasn't unique. Really, they were only one of the units under the umbrella of "Special Attack" forces.

CMH Online lists a ground force in 1942 as a precursor to the Special Attack forces. They weren't exactly suicide missions but were small groups sent out at night, meant to decimate enemy bases with hit-and-run tactics. At least some of the men were expected to survive, though the mentality was the same — maximum damage with the least resources.

But there were other official Special Attack forces, too. Atsushi Takatsuka mentions the Kaiten — human torpedoes. They were manned suicide torpedo missions. One man would be seated inside the torpedo and drive it into the side of an enemy ship, exploding on contact. In the same vein, there were also suicide crash boats and tiny submarines that served similar purposes.

By the very end of the war, that desperation really cranked up, as did the suicide missions. Sometimes, individual soldiers would put on scuba gear and hide just off the coast, armed with explosives on bamboo sticks, destroying ships that passed over them. Or there were their land counterparts — soldiers who strapped bombs to their bodies and hid in pits, blowing up tanks that rolled over them.

There were special vehicles

The Special Attack forces were created with a straightforward goal in mind — the most destructive effect with the lowest cost, in terms of both materials and people (via CMH Online). And so there were new vehicles designed just to service this end.

Atshushi Takatsuka explained how that worked. The little suicide crash boats, meant to sink ships just off the coast, were made almost entirely of wood. Only one person navigated it, and it just ran on an old Toyota motor. All of that extra space and money went toward loading the boat up with explosives. And when it came to the Kamikaze pilots, they got specific planes, called the "Ohka." These were basically little gliders with a bunch of explosives shoved into the nose. They didn't have anything unnecessary — they were even hooked onto the bottom of a larger plane, rather than taking off on their own — with parts made out of wood instead of metal. It didn't need to be strong, after all. They weren't all that fast or even maneuverable, but they got the job done.

That said, not all of the planes were specially made for suicide missions. The Guardian mentions that, by the end of the war, desperation had gotten bad enough that any old planes were also being used, stripped of radio equipment and weapons and loaded with explosives.

The Kamikaze pilots had special training

One of the myths out there surrounding the Kamikaze pilots is that they were untrained, and Japan just needed bodies to fly planes into ships. To be entirely fair, there is a little bit of truth behind it. Atshushi Takatsuka said in an interview that, yes, the military was beginning to pull Kamikaze pilots from those who were only partially done with their training. Again, desperation. (By 1945, they'd cut the second part of the aviation training course entirely). CMH Online adds that, compared to other tactics, and with enemy anti-aircraft technology existing, suicide missions took relatively little instruction or experience.

But they didn't get nothing. They just got different, more practical training. After all, flying in a Kamikaze mission is really different from flying, well, any other kind of mission. They had to know how to deal with weird problems like the gravity when they would be dropped off the bottom of another plane. That's not exactly a normal situation. And since they were dive bombing at other craft, they had to be able to deal with that sort of piloting. According to National News, sometimes that training involved piloting straight towards the ground, then turning upward at the last moment (just a little terrifying, no?) Other times, apparently it included being launched from a catapult (a little stranger, but just as terrifying).

Participation as a Kamikaze pilot was voluntary (but not really)

Even though Japan was deeply desperate for more manpower, it wasn't like they just forced people to become Kamikaze pilots. There was a whole questionnaire and everything! They had a choice. Except, did they really?

So, yes, there were actually questionnaires handed out regarding recruitment as a Kamikaze pilot — that's true. Stories collected by The Guardian and National News from pilots trained for Kamikaze missions refer to some similar circumstances. A slip of paper with three options — "I passionately wish to join," "I wish to join," and "I don't wish to join." (The wording varies slightly by account, but the gist is the same.) Atsushi Takatsuka mentions the same sort of thing. They were taken into a room and given five minutes to decide if they would volunteer, decline, or let their commander decide. Another story reported on by the BBC mentions that pilots were sometimes corralled into a big group and asked to volunteer.

On the surface, it does sound democratic, and, full disclosure, it did start that way. But later, there was just the appearance of choice. The use of big groups peer pressured everyone into volunteering, and even when three choices were given, most of the men knew there was only one "right" answer. It was a scary thought to refuse, and sometimes, even those who dared to would supposedly be brought back and told to pick the "right" answer.

Some of the Kamikaze pilots were eager

Even though volunteering for becoming a Kamikaze pilot was a little less than democratic, that didn't mean that all of the men were unwilling. A number of them were actually eager.

Osamu Yamada told the BBC that, when the call came for Kamikaze pilots, he joined willingly. He was single at the time and had nothing holding him back. The ideology of the Kamikaze pilots felt pure — a genuine love of country and a willingness to die in defense of it.

The Guardian talked to Hisao Horiyama, who made a pretty similar statement. At one point, Emperor Hirohito personally visited his unit. From then on, he felt like he had no choice but to die for him. It was a worthy cause, and even then, it wasn't like he thought much about dying. It was just his duty, but also, he saw it as a path toward glory — a way to finally prove himself to his father.

That glory is something Atsushi Takatsuka mentioned, too. Most of the Kamikaze pilots were young — 17 or 18 years old. And they wanted to make a name for themselves, as teenagers do. That was just compounded with the competitive nature of the military. Volunteering to be a Kamikaze pilot not only gave them posthumous honors but also let them feel recognized, feel like they'd somehow left all their peers in the dust.

Most of the Kamikaze pilots were just scared

There's kind of been a tendency to paint the Kamikaze pilots as hyper-patriotic and reckless, willing to die without a second thought. But for as well as that might fit in a movie, the truth is a lot darker. A majority of the pilots probably didn't think that way. They didn't want to die.

Takehiko Ena told The Guardian that he remembered the moment he found out he'd been chosen. He'd been a university student, and at the news, he "felt the blood drain from [his] face." He remembered everyone congratulating each other and then telling himself that he'd been chosen for this, but deep down? He realized that there was nothing to celebrate, and he was just scared. A lot of them were.

Keiichi Kuwahara has a similar tale. As reported by the BBC, he was only 17 when he felt like his fate had been sealed. He didn't feel any of that patriotic fervor. He could just think of his family, of his mother and sister whom he was sending money to. The last thing he wanted to do was leave them alone, and he just wasn't ready to die.

Both men were glad they didn't have to. Kuwahara's engines malfunctioned, and he felt fear turn to relief when he had to return, and Ena recalled feeling glad that the war was over. It was a chance to look forward and rebuild instead.

Kamikaze pilots accepted the inevitability of death

All of the Kamikaze pilots had to come face to face with an almost-certain truth — they were going to die. Some were willing, some weren't, and some only did it for each other, so that their friends might not have to make the sacrifice (via National News). But the same sad truth awaited almost all of them.

Their last few days and hours were fittingly somber. Atsushi Takatsuka explained that there was no pomp and circumstance, no ceremony, no ritual. What they did was really just up to the pilots. Some would bury locks of their hair behind shrines. Others would drink their anxieties and fears away. Sometimes, they got a few days vacation to go back home and see their families one last time. Then, on the day of the mission, their last few minutes were spent aimed at an enemy craft, with the instruction to send one last morse code message — just a long, uninterrupted signal. And on the receiving end, if that long signal just ended with sudden silence, then the mission was successful.

The Kamikaze pilots have since been associated with the Japanese cherry blossom and for really poignant reasons. In a way, the cherry blossom signifies a detachment to life, says Takatsuka — it's simple and beautiful but impermanent. It won't last forever, but there was something beautiful in that.

Post-war antagonism

The post-war period wasn't kind to the pilots. The Allies occupied Japan for about seven years following the end of the war, and they had it in mind to ruin the reputation of the Kamikaze pilots (via BBC). The pilots weren't heroes. They were insane fanatics, too reckless for their own good, according to Atsuhis Takatsuka. The new government really wanted to push that, and eventually, the public treated them with indifference at best, or contempt at worst (via Kamikaze Images).

Suddenly, it was hard for them to find jobs or even apply to schools. A stigma had emerged about them, and the "Special Attack Syndrome" seemed to imply that they couldn't return to normal lives. They'd been obsessed with dying with honor and couldn't find a new purpose.

But that was based in very little fact. Yes, that adjustment was hard for some of them, but can you really blame them? They'd trained themselves to accept death — it's an extreme mindset to come back from.

Sadly though, those assumptions haven't really gone away. Some younger generations in Japan — who grew up with a pacifist constitution — see them as idiotic, and the views from other countries, like America, are even worse. The view that they were suicidal fanatics who loved death is still around (via Kamikaze Images), and using "kamikaze" as slang for "reckless and insane" really plays into that negative view, even if passively.

Comparisons between terrorists and the Kamikaze pilots

In the post-war period in Japan, the Kamikaze pilots were already dealing with some level of antagonism, but in much more recent times, there's been a potentially worse comparison that's been drawn to them. Namely, terrorist attacks, especially in the direct aftermath of the September 11 attack on the World Trade Center. And that's not just some lazy speculation. A news release from Stanford specifically described the attacks as something between "a kamikaze aircraft on one hand and a hijacked aircraft on the other."

Atshushi Takatsuka does admit to some similarities. He references a belief in self-destruction common between both, and they both would carry out their missions in service of something bigger (at the time, most of Japan viewed the emperor as someone godly).

But he's also insistent that it's not the same thing, and the differences are really important to note. Terrorists tend to go after civilian targets. The Kamikaze pilots (and all the Special Attack forces) were only sent after military targets. The BBC also includes the fact that the pilots only did what they had to because it was a war, and they really had little choice. It's a different set of circumstances, and implying they're the same is more than a little unfair.

Nationalism and heroism

During the war, Japanese nationalism saw to it that the Kamikaze pilots were seen widely as heroes. Atshushi Takatsuka explained that the air force had once been the place for rejects from the Imperial Naval Academy, but suddenly, it became a viable and respected career. Advertising shot through the roof, too, with posters saying to "Move Forward, One Hundred Million! You Are Fireballs." It was all an ideological ploy so that the public would look up to the Kamikaze pilots.

After the war, that sentiment completely fell apart, but in the decades after, it came back. According to the BBC, as early as 1952, nationalists wanted to rewrite the antagonistic narrative the Allies had left. The pilots' actions weren't shameful and weren't a crime by any means. They really pushed this view through the 1970s, 80s, and 90s, to little resistance. The pilots became seen as heroes again.

And that's largely been the case in Japan through to this day. Kamikaze Images says that the Japanese people will often remember the pilots with tears in their eyes. They weren't nameless, faceless masses, but individual people, a lot of them really young and well educated. But above all, they were brave. There's a purity in being able to do the brave thing, even in the face of absolutely hopeless odds. But that's what the pilots did, and they deserve honor for that.

A tragic tale

Above everything else, though, the story of the Kamikaze pilots is a tragic one. Documents and pictures have been collected in the years since the war in memory of the pilots who gave their lives, and they really do speak for themselves.

Kamikaze Images mentions that a lot of the pilots were university students, and their last writings show how they loved learning and delved into philosophical thoughts, coming to see texts in a new light now that they were facing death. Another photo shows a group of young pilots all standing together and smiling, the pilot in the middle cuddling a small puppy. Even with death at the door, they managed to look cheerful.

National News has a couple of other letters, too, addressed to loved ones of the pilots. One pilot wrote about the way the rain fell, the soft sound of the radio, everything he was still hearing because the rain had delayed his mission. Another pilot wrote to his parents, apologizing for not being the best son, but that he would die with a smile on his face and wait for them on the other side. And a third wrote to his fiancee, begging her to marry him in the next life, and the next, and in every one after that.

They're all universally heart-wrenching and really deserve a read. Summary doesn't nearly do them justice.