The World's First Black Fighter Pilot Was More Important Than You Realize

The period immediately after the Civil War, known as Reconstruction, wasn't an easy time in the United States, much less in the war-ravaged American South. In an attempt to totally reboot Southern society, folks tried a whole bunch of things in order to figure out how to better integrate newly freed Black people into daily life... or at least, that's what they claimed.

In reality, American society remained highly racist and segregated in the aftermath of the war, limiting the potential and opportunities for Black and mixed-race people born at the end of the 19th century. Yet being smart, determined, and resourceful has always been a path to success no matter what your race, nationality, or creed. Young Eugene Bullard was living proof of that. Born October 9, 1894, in Columbus, Georgia, to William Octave and Joyakee, a French-Caribbean freedman and a local Creek woman, Bullard became the first Black person — and first mixed-race person, too — to officially serve as a fighter pilot, as Aviation History relates. He would ultimately serve with valor in World War I and inspire other aviators like Bessie Coleman to take to the skies in pursuit of their own dreams.

Eugene Bullard escaped a life of poverty and racism

Rural Georgia at the turn of the 20th century was a brutal place for a young Black man with dreams of adventure. After his father narrowly escaped a lynching for standing up to a white bully at the railyard where he worked, as AFS Global notes, young Bullard feared for his family. So, Bullard ran away in 1906 at the tender age of 11 in pursuit of a better life. According to The Bitter Southerner, he made the right decision when the horror of violent racism touched his own family — his older brother Hector, who was studying to become an agricultural manager, was later lynched for trying to take administrative control of a peach orchard that belonged to their mother's family.

On his own in the deep South, Bullard took up with a band of Romani people he met in Georgia, known as the Stanley Clan according to Mental Floss. With them, Bullard learned aspects of Romani culture, groomed and raced horses, and heard tales of life in Europe, many of which must have echoed the stories of France he'd heard from his French-Caribbean dad. To young Bullard, it seemed like France was the place to be at the dawn of the 20th century, especially if you had great aspirations and energy but were held back elsewhere by the color of your skin.

Bullard stowed away on a ship crossing the Atlantic

Between his father's stories and the tales of the Romani he fell in with during his adventures in the American South, Bullard became convinced that the only place he would experience freedom and equality was Europe. In 1912, he stowed away on a ship bound for Europe. Thus, as Georgia Humanities recounts, he stowed away on the transatlantic freight liner Marta Russ and headed for his next adventure.

And what an adventure! Turns out, the Marta Russ was a German ship headed for Aberdeen, Scotland, and not the French ship that he may have hoped it was. Bullard was quickly found by the crew, but rather than shove him overboard as the captain initially threatened, they allowed him to work for his passage by helping to maintain the ship's all-important coal furnaces, says Encyclopedia.com. At the journey's end, they deposited him safely in Scotland, where he worked a series of odd jobs — including acting as a lookout for a gambling bookie — before starting to train and fight with a local boxing gym. Aviation History points out that he quickly became a bantamweight champ.

Eugene Bullard became a champion boxer and performer

With his unmistakable prowess in the boxing ring, quick wit, and knack for languages, Bullard quickly became a fan favorite. In addition to his boxing, he joined a vaudeville troupe and began touring as both a lightweight champ and a deft comedy performer. As part of Belle Davis's Freedman Pickaninnies, an African-American touring vaudeville troupe, he left England and finally made it to France in 1913, where he decided to stay, as the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum recounts. As he wrote in his autobiography quoted by the Smithsonian, "it seemed to me that French democracy influenced the minds of both black and white Americans there and helped us all act like brothers."

Bullard would continue to tour, according to Black Past, while building his knowledge of French and his love for the country, over the next year or so. Learning French customs and life, establishing himself as a noted performer, and making connections all came easily to the charming young Black man from rural Georgia. It seemed he'd finally found both the adventure and the safe, free life he craved. That is, until World War I broke out.

In 1914, Bullard enlisted in the French Foreign Legion

Almost the instant hostilities broke out in 1914, Bullard enlisted in the famous French Foreign Legion to defend his adopted homeland, as Black Past relates. He was just 19 when he shipped off to Morocco as an infantryman, having promptly enlisted on his birthday. Bullard quickly proved that his bravery didn't end in the boxing ring, as he was willing to keep on fighting when most folks would have given up.

According to Black Books Matter, he fought through grievous injuries at a number of battles. Bullard worked his way up from foot soldier to machine gunner, losing most of his teeth (but gaining a spiffy set of dentures) and taking a crazy amount of shrapnel to his thigh during the course of battles like the Battle of Champagne and the Battle of the Somme. As a biography by historian Robert Vanderpool, writing for Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson, notes, he had a knack for getting into hot water. Ultimately, Bullard fought at some of the bloodiest battles in the first half of World War I and kept coming back for more.

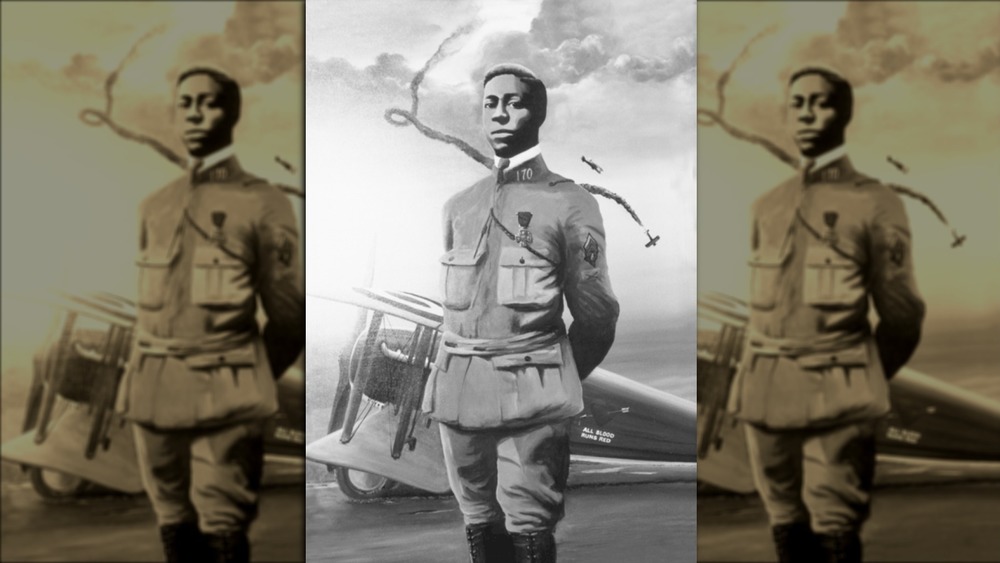

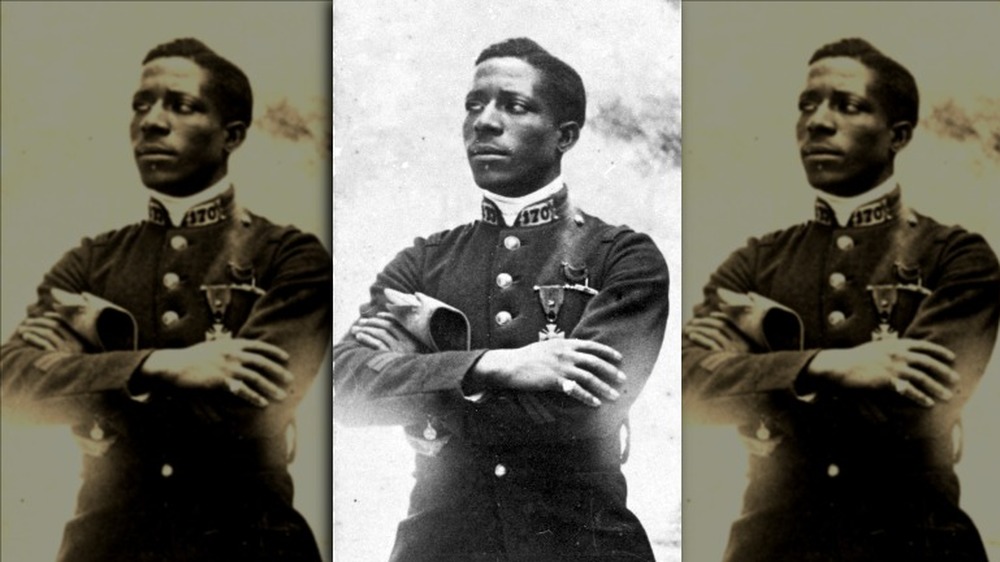

Already a decorated war hero, Eugene Bullard took to the air

Though his wounds had never kept him from surging back quickly, Bullard's luck could only hold for so long. He was seriously wounded at the Battle of Verdun on March 5, 1916, as Find A Grave notes. After this, Bullard was sent to a military hospital in Lyon to recover, according to the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. He was awarded a series of medals for bravery and combat service by the French government, including some of the highest military honors available in France, such as the Légion d'honneur, the Médaille Militaire, and the Croix de Guerre, as Military History Now reports.

Unfortunately, this time around, Bullard's wounds were enough to keep him out of the action and the horrific trenches of World War I. Historian Robert Vanderpool notes, via Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson, that the military hospital declared his leg wound bad enough to prevent him from returning to field service. Well, as an infantryman or ground gunner, that is. But there were other exciting new options open to a tremendously brave man, including service in the newly established air corps. Now a decorated war hero and still eager for action, Bullard didn't hesitate in finding a new path forward.

Eugene Bullard became a pilot on a bet

Though flying had fascinated him for years, Bullard never really thought of becoming a pilot until he witnessed the aerial aces of World War I. While in Lyon recovering from his wounds, he was told that he'd be on desk duty, as the injuries he had sustained were simply too bad for him to return to the field. Drinking away his woes in a local tavern, according to Aviation History, he got into a conversation with other soldiers. Bullard wound up taking a $2,000 bet that he couldn't become a pilot.

He won, obviously.

Via Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson, historian Robert Vanderpool notes that Bullard's eclectic previous life paid off here, as the air corps wasn't open to just anybody, no matter the color of your skin. Therefore, getting in took a little doing. But because Bullard had hobnobbed with some pretty important people as a boxing champ and during his vaudeville days, he was able to call in some favors from friends who were high up in the French government and military. So, in November 1916, Bullard joined the Aéronautique Militaire, as the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum recounts. He collected the money from that bet a few months later when, according to Military History Now, Eugene Bullard became the 6,950th French military pilot to earn his wings. Bullard was also then the first African-American to become a qualified fighter pilot anywhere in the world.

Racism kept Eugene Bullard from fighting for America

As the newest member of the French air corps, Bullard was assigned to the Layfayette Flying Corps, a group of American Legionnaires who regularly flew with their French counterparts. He also managed to get an extra salary to compensate for the incredibly risky new job, says Aviation History. Within three days, Bullard was taking short flights and learning the ropes with the rickety French training planes.

But something felt off. Bullard was only around French pilots and never other Americans. Even after graduating from training school, he kept getting assigned to ground duty. Newer pilots took to the air and Bullard was still grounded. He traveled to Paris for a physical, looking to join the increasing number of Americans fighting in the area now that the United States had joined the war, and was told he was fit for duty and nothing more, according to Aviation History. But he was still on the ground. What was the problem?

As it turns out, despite white soldiers being transferred from the French Foreign Legion when American entered World War I, Bullard was prohibited from serving with his countrymen because of his race. Historian Brenda Mandt, writing for The Museum of Flight, notes that the officer in charge of integrating the U.S. and French forces at the time was a virulent racist who denied Bullard entrance simply because of his skin.

Eugene Bullard fought at least 20 aerial dogfights

Despite the systemic racism and frustration he encountered, Eugene Bullard didn't stop. He kept practicing and training and was so eager when he was finally assigned an air patrol that his commander had to remind him to chill out, as Aviation History points out. On September 8, 1917, he got his chance to serve in the skies and engaged the enemy on his second-ever patrol round.

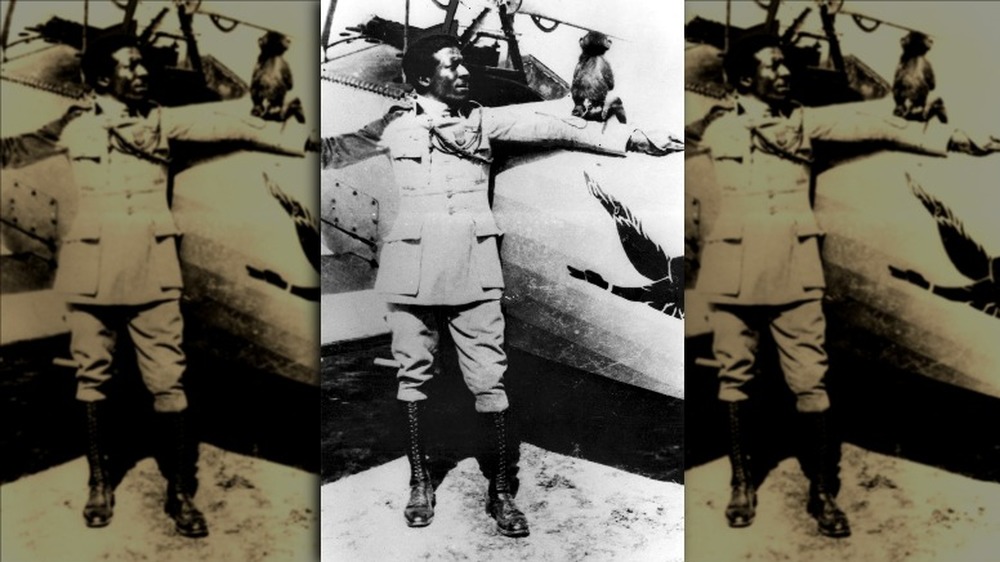

Bullard was fearless in the air, if not the most skilled pilot in the corps. In an aerial dogfight a month later, he took more than 90 bullets to his plane and made a kill on a German biplane before managing to return to French lines and crash landings (via Aviation History). But the kill couldn't be confirmed by witnesses on the ground, so Bullard wasn't quite an "ace" yet. Still, he repainted his plane, added a graphic of a bleeding heart pierced with a dagger, and named his ride "Tout sang que coule est rouge" ("All blood runs red"), as Historic America reports. He eventually made at least 20 sorties and had either two unconfirmed or one confirmed and one unconfirmed kill according to different sources, says historian Richard Vanderpool via Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson.

Eugene Bullard became a celebrity nightclub owner

Despite his heroism and uncanny ability to shoot the heck out of the enemy whether on the ground or in the air, Bullard was drummed out of the military by racist policies of the time. According to The Museum of Flight, Bullard got into a fight with a white French superior officer who was reportedly racist. Bullard was transferred back to his old infantry unit after cold-cocking the guy. Because of his leg injury, he had to ride out the waning days of World War I in a support capacity.

After the war, with 17 new military medals to his name, Bullard turned to his old entertainment contacts and started performing around Paris, according to Explore the Archive. As The Lawton Constitution recounts, he would eventually marry a French woman, have two daughters, and become a staple of the Paris social scene by the early 1920s. He hung around with Louis Armstrong and Josephine Baker and opened a series of super-successful clubs in Paris. Find a Grave notes that he also opened an athletic club, teaching others how to emulate his boxing success.

Eugene Bullard spied on the Nazis

Even after the war, things weren't peaceful in Paris and Eugene Bullard was always ready for action. As tensions ramped up towards the outbreak of World War II, Bullard used his linguistic skills and status as a celebrity club owner to spy on local German sympathizers and pass information to the French resistance and his military contacts.

Historian Richard Vanderpool recounts that plenty of German officers wanted to hobnob with celebs and experience the decadence of French life in Paris, and that they often didn't consider the gracious and charming Black host a threat (via Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson). But, as biographer Phil Keith notes at Sag Harbor Express, he was perfectly fluent in German and knew how to use free Champagne to get folks talking. Bullard may have been the first to find out that the Nazis planned to invade Poland and passed that information on to his military contacts and the French Resistance. However, he was ignored, because it was considered simply too outrageous an act even for the ambitious German forces. Sadly, he'd later be proven correct.

When war broke out, Bullard promptly rejoined the military and served as a machine gunner defending the city of Orleans in 1940, as The Lawton Constitution recounts. Unfortunately, he suffered yet another injury and decided that it was time to end his military career.

Bullard worked odd jobs in New York at the end of his life

With his war wounds and young daughters to think about, Bullard let his friends convince him that he needed to get the heck out of Europe, as the Nazis didn't take kindly to fierce Black folks. He returned to the United States for the first time in 30 years to recover and rebuild.

According to Explore the Archive, he was able to use reparations from the French government over the destruction of his Paris club to buy an apartment in Harlem. But in the U.S., he was shut out from the social scene and celebrity he'd had in Paris, and doubly held back by still very prevalent American racism. No longer known as a self-confident war hero, raconteur, and general man-about-town, Bullard ended up working odd jobs as a longshoreman, elevator operator, and perfume salesman, according to The Lawton Constitution.

Bullard even had a brief stint as an interpreter for Louis Armstrong at various gigs, but ultimately spent most of his later years alone. His grown daughters had married and moved out, and most of those who knew him in the United States had no idea that they were talking to the "Swallow of Death," one of the bravest and most decorated French Legion soldiers of World War I and the inspiration for stories ranging from Ernest Hemingway's "The Sun Also Rises" to Dooley Wilson's piano-playing character in the movie Casablanca, as Sag Harbor Express notes.

Bullard is finally getting the honors he earned

Though he was cast into obscurity in his home country, in France, Bullard was still remembered and honored. According to Aviation History, French President Charles de Gaulle himself invited Bullard to return to France in 1954 to help rekindle the flame at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier under Paris' Arc de Triomphe, not far from the Eiffel Tower. A few years later, he was made a Chevalier de la Légion d'Honneur to reward his service.

Still, in the U.S., Bullard was largely unknown. There, he lived a quiet life operating the elevator at Rockefeller Center. His uniform was covered with his medals, which sparked a conversation with the first host of the Today Show, according to Sag Harbor Express. He was invited onto the show in the late 1950s to talk about his adventures.

Eugene Bullard died of cancer in 1961 at the age of 66. He was buried with full French military honors in the French section of Flushing Cemetery in New York, as Find a Grave notes.

Today, Bullard is finally starting to receive the honor he deserves in his native country, not just in France. CNN reports that the unveiling of his statue at the Museum of Aviation in Georgia was attended by several living descendants. Georgia Humanities further points out that he was finally recognized by the U.S. military in 1994 when he was posthumously commissioned as a lieutenant in the United States Air Force.