The Untold Truth Of The Black Death

The Black Death wasn't a singular event, but a plague that decimated entire populations several times. It was described by the Italian poet Giovanni Boccaccio, who wrote (via History), "In men and women alike, at the beginning of the malady, certain swellings, either on the groin or under the armpit... waxed to the bigness of a common apple, others to the size of an egg, some more and some less, and these the vulgar named plague-boils."

The Black Death isn't just fascinating for the devastation it caused, but also for the invaluable look into society it provides: How did people deal with such a terrifying plague that killed a still unagreed-upon number of people? Did it pull communities together, or push them apart? The answer to that is, in some cases, pretty surprising, especially when viewed in the context of a post-COVID world. It's not a far-fetched comparison, especially when it comes to the attempts that were made to control the outbreaks: Two of the best weapons against the plague were quarantine and social distancing.

Did it work? Maybe. Jane Stevens Crawshaw, an Oxford Brookes University lecturer in early modern European history, explained that it wasn't just disease that made the Black Death so dangerous: "There are risks with any sort of epidemic of social breakdown, widespread panic, or complacency, which can be just as dangerous. There are a lot of emotions that need to be acknowledged and preempted and that was part of public health policy 600 years ago as much as it is now."

What exactly happened to people?

How would you feel about going back in time to get away from first-world problems? Pretty good? Medical history might change your mind. According to the World Health Organization, the plague commonly known as the Black Death killed around 50 million people.

The 14th-century plague we're talking about was bubonic plague, which inflames the lymph nodes as it multiplies, turning them first into swollen "buboes" and then into open sores. That's in addition to fever, chills, fatigue, and vomiting. Ole J. Benedictow, a history professor at the University of Oslo (via History Today), estimates this medieval plague outbreak had about an 80 percent kill rate. The one consolation was that victims only lived for around three to five days after developing the first symptoms. Less consoling is the three- to five-day incubation period where a person is infected but asymptomatic, giving them plenty of time to spread it all around.

And just as death waited for victims, so did indignity. A contemporary chronicler from Florence wrote of the dead laid in a pit in the church graveyard, covered with a layer of earth, and then another layer of corpses. He likened it to "just as one makes lasagne with layers of pasta and cheese." Good imagery, bad ending.

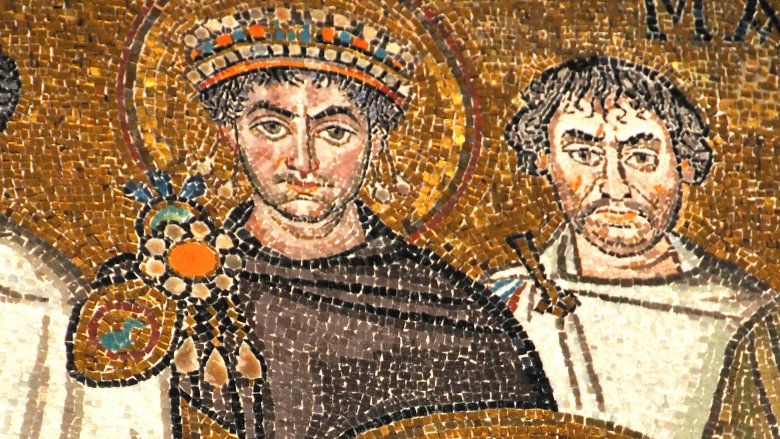

The 14th-century Black Death wasn't the first

The devastating plague outbreak we now call the Black Death swept across Europe between 1346 and 1353. The years before are a little hazy, but we do know this wasn't the first time this happened. The first started in A.D. 542 during the reign of Justinian, and it lasted for at least 225 years.

Well, 542 is when it came to Constantinople, at least. It had been lurking in the shadows of the Byzantine Empire for a while, and was traced from northeast India and China to Egypt, moving along the trade routes.

It was mostly bubonic plague, probably with a little septicemic and pneumonic plague mixed in. The devastation and sickness lasted for centuries because of a weird confluence of factors that started in about A.D. 536 with the first of two volcanic eruptions. The air was filled with debris from the eruptions, and it was made even worse when a piece of Halley's comet collided with Earth and kicked up more dust. The climate cooled, crops failed, and people were vulnerable. The planet became the perfect breeding ground for plague. So the 14th century was bad, but the sixth might have been even worse.

No one is sure when or where it really started

Justinian's plague disappeared in A.D. 750, and there wasn't another large-scale pandemic recorded until the Black Death. It's not entirely clear where the 14th-century outbreak came from, but historians love to argue about it.

There are a couple of predominant theories. We know Europe had only recently opened to Eastern trade in 1346, and while there hadn't been any major outbreaks for centuries, there were pockets of plague. One was in Asia's Lake Issyk-Kul (pictured), where archaeologists have pinpointed a plague dating to 1338 and 1339. It's also been found in China throughout the 1320s. It was in Europe by late 1347, and pilgrims, merchants and caravans, and soldiers carried it to Mecca and Britain in 1349.

One thing we do know is how it entered Europe: through the ports of Messina and Genoa. In October 1347, trade ships made port in Sicily, filled with lovely silks from the Far East and also with dying sailors. At the same time, a Tartar siege on a Genoese trading post ended because of Tartar plague. As a parting gift, they catapulted their dead into the city. By the time trade ships returned to Genoa in January 1348, most of their crews were dead or dying.

It may have been driven by climate change

The plague had another devastating consequence — it pretty much ruined the reputation of rats, in spite of the fact they've been found to be at least as smart as college students at some tasks. We condemn them as harboring plague and being what scientists call "generally icky," but according to research by the University of Oslo (via the Smithsonian), rats weren't responsible for keeping plague dormant before reintroducing it to humans.

Researchers looked at pockets and outbreaks of plague during the Black Death. They found plague corresponded with climate fluctuations, even when it came to temporary lulls in the death tolls. Remember how large-scale climate change seemed to exacerbate the plague in the sixth century? The same factors could have been at work later. When the weather gets warmer and wetter, rat populations decline. That means plague-carrying fleas need to find other homes, and even though they would generally prefer rats, they're forced to migrate to domestic animals and ultimately to humans. As if we didn't have enough to worry about with modern-day climate change, now you'll be thinking about how you're becoming the last resort for plague-loving fleas. Good luck not getting itchy while thinking about it.

It spread to Norway when a ghost ship ran aground near Bergen

You know it's a strange world we live in when The Guardian actually has to run a story with the headline, "Don't worry — a ghost ship crewed by cannibal rats probably isn't about to hit the British Isles." Whether you laughed at the idea or laughed a little nervously, you probably remember hearing the viral stories that circulated in 2014. It turns out the idea isn't that far-fetched, because that's exactly how the plague spread to Norway.

Plague spread fairly slowly, and word reached Scandinavia before sickness did. The northernmost reaches of Europe even thought they might escape the Black Death, until sometime in late 1349 or early 1350. When a ship left England in 1349, it was heading north carrying a hefty cargo of wool and plague. Every single person on the ship succumbed, but the ship kept its course. It ran aground not far from Norway's Bergen harbor (pictured), dumping fleas and rats into the previously untouched country. It's unclear how many died — estimates suggest it was about a third of the country — but we do know it spread from Norway into Sweden and finally Russia. Not so funny now, is it?

The Black Death led to the world's first quarantine laws

We have a weird fascination with the post-apocalyptic today, but these folks were actually living through what must have seemed like the End Times. For many, it absolutely was. It's impossible to imagine being in a position of authority and needing to deal with the outbreak, and according to a piece published in the academic journal Clinical Infectious Diseases, one city's leaders developed a now-familiar way of dealing with plague: quarantine.

The idea of separating someone who's ill from the rest of the population dates back to the Old Testament, when lepers were condemned to a life of exile. But a formal sort of quarantine — and the word itself — goes back to the medieval port city of Ragusa, which today is Dubrovnik, Croatia. In 1377, the city's council passed a series of laws that included a month-long isolation period for newcomers to the city. Anyone who wasn't officially tasked with caring for those in isolation was forbidden from visiting them, or they'd need to serve out a 30-day stint there, too. The idea spread to other cities, and eventually the 30-day period ("trentino") became 40 days ("quarantino"), though no one's sure why. It may have had something to do with the biblical significance of 40 days, or the Greek idea that contagious diseases needed 40 days to show symptoms. Raise your hand if you're thankful for antibiotics.

Doctors tried everything they could think of

It wasn't that long ago that we thought having a uterus and drinking absinthe were causes of madness, so when scores of people started dying, the doctors trying to cure it were in hopelessly over their heads.

They tried all kinds of cures rooted in the most serious beliefs of the time. The Catholic Church's belief that God sent illness to punish the sinners of the world led to people trying to cure themselves by prayer, pilgrimage, and even self-harm. The flagellants whipped themselves to show how sorry they were, but it didn't help.

The medical community was still governed by the ancient Greek idea that illness was caused by an imbalance in the body's humors, so other cures were focused on trying to get everything back in harmony. Doctors tried blood-letting, lancing boils, burning herbs, and bathing in rosewater or vinegar. (No reports of singing lessons for harmony, though it probably wouldn't have worked.) There was even a belief that plague was caused by stiff air, so ringing bells and letting birds fly around was another practice. Doctors tried giving their patients drinks of vinegar, 10-year-old treacle, and minerals such as mercury. Others tried rubbing things on the boils, like pigeon and snake parts, onions, or herbs. Sounds nutty to our modern ears, maybe, but those who stayed to treat their dying patients knew their own chances of survival were poor, and still did the best they could.

That terrifying plague doctor costume was carefully designed

In the 14th century, the plague doctors didn't have that infinitely creepy, bird-like mask we think of today, but they were around. Many doctors realized they were fighting a fight they couldn't win, so they hightailed it out of town. Cities and municipalities hired in others — the plague doctors — to care for the dying. While some were complete frauds and others did it in hopes of swindling devastated families out of everything they owned, they're one of the most iconic symbols of the Black Death.

The creepy costume wasn't designed until the 17th century, and it was the creation of the favorite physician of the Medici family and the French royal court. Charles de Lorme created it in hopes of isolating himself from the plague his patients were carrying, so the entire head-to-toe thing had a waxy coating. Gloves, boots, and the leather hood were tied shut with leather strips, and the eyes were protected by glass domes. Finally, let's talk about that mask. The beak was filled with herbs (usually myrrh, camphor, mint, or cloves) in hopes they would filter the air. The French went a step further, and their herb-filled beaks would be set on fire to produce smoke they thought was even more cleansing.

Most of the time, it didn't work. The plague doctors who didn't die often became outcasts, not to mention the stuff of nightmares.

Plague pits are rarer than you think

Contrary to popular belief, the London Underground doesn't weave around in order to avoid plague pits. (It was a cost measure.) There are no records of construction crews uncovering human remains while digging the Underground, and most of the tunnels are 40 to 80 feet down, much deeper than any plague pit would be. There are a few times the Underground went through cemeteries, but what about the plague pits supposedly peppered all over the country?

University of London historian Vanessa Harding (via the BBC) says that even when plague got really, really bad, most of the victims were still buried in cemeteries and other designated burial grounds. It makes sense, too. As she says, people needed "stability and comfort" during those dark times, and giving their loved ones a proper burial was part of that. Most stories of plague pits are legend and lore, and we even know who is at least partly to blame for popularizing the idea: "Robinson Crusoe" author Daniel Defoe, who listed some fictional plague pits for his drama "Journal of a Plague Year." Real plague pits — like the one in East Smithfield or the one at Lincolnshire's Thornton Abbey — are rare finds, but even those bodies weren't just dumped off the death cart. They were buried carefully, or at least as carefully as they could be by people who were also dying.

It had a strange impact on overall population health

Sure, 50 million people died during the Black Death, but millions more survived the pandemic. When researchers from the University of South Carolina looked at the skeletons of those who had survived, they found that post-Black Death people were generally healthier and lived longer. The number of people living to at least 70, for example, nearly tripled in the years after the pandemic. There were more people living even past 50, and it was a trend that seemed to continue for the next 200 years.

They aren't entirely sure why the trend is there, but there are a few suggestions. It might be as simple as improvements in diet and standards of living, but it might also be because the Black Death took away the weakest section of the population. According to anthropologists from the University at Albany (via LiveScience), the plague didn't kill everyone. When they looked at skeletons of those who had succumbed to the plague, they found the disease was much more likely to kill the weak, the elderly, and those who were already sick. The population rebounded to be even stronger and healthier after they were gone. Sorry, weak links.

The Black Death changed our genetics (a little)

Just in case you were feeling all safe and cozy there behind your computer, know that the plague is still around. It's still mostly the same, too. Researchers analyzed the powdery residue inside the teeth of plague victims of London's East Smithfield Cemetery and were able to map the entire genome of the bacteria that caused the Black Death (via LiveScience). When they compared that to the genome of modern plague, they found only slight differences.

Something else did change during the plague years, though, and it's us. Researchers from the Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center (via LiveScience) found there's a difference in the genes of European and Roma peoples compared to those from India. About 20 genes seem to have evolved simultaneously in Europeans and in the Roma but not in India, where there was no major 14th-century plague outbreak. Several of the genes govern immune function, and one cluster specifically causes a major response to plague bacteria. That suggests the Black Death sped up human adaptation to help some of us survive. At least something's looking out for us.

One English village risked it all to stop the plague from spreading

It was the summer of 1665 when the Black Death arrived in the English village of Eyam, having traveled up from London on pieces of cloth carrying infected fleas. The tailor, his assistant, and their families were among the first to die, and while there was arguably still time for the healthy to flee, that's not what they decided to do at all; if they carried the plague to neighboring villages, they would only spread death. So, they did something incredible: They stayed, they buried their dead, and they waited to die.

Stories from Eyam are chilling, and by the time the plague had run its course, 267 of the village's 344 residents were dead — including the stonemason, which left survivors to etch the names of their loved ones on gravestones themselves. Some buried entire families, like Elizabeth Hancock — she lost and buried her husband and six children over the course of eight days. (Their graves are pictured.) Meanwhile, others erected stones around the village that marked locations for trade. Eyam residents left coins — disinfected with vinegar — in exchange for food.

It was the local rector, William Mompesson, who spearheaded the quarantine movement, and would write of knowing that his wife was soon to join the dead when she reported that to her, the air smelled sweet. That sweet smell? A sign the infection had already begun to spread rot through internal organs. Eyam's sacrifice helped kickstart practices of disinfecting, quarantine, and disease prevention.

It gave rise to the Danse Macabre and Memento Mori motifs

The practice of keeping trinkets — such as locks of hair — from the dead is called memento mori, and the rise in popularity of memento mori is just one of the bizarrely gruesome things that happened during the Victorian era. The idea was around much longer than that, though, and along with the danse macabre motif, it got started during the Black Death.

In a nutshell, both are artistic trends that represent death in a very gruesome way. Memento mori involves realistic death imagery — think of tombs carved with the stone effigies of rotting corpses — while the Danse Macabre was the depiction of death — often as skeletons, sometimes as rotting corpses — walking alongside or dancing with the living. Both developed during the 14th century, when outbreaks of the plague brought entire cities face-to-face with gruesome, painful deaths on a catastrophic scale. While death had previously been viewed as a peaceful end to a mortal life and a transition that would see the soul ushered into a heavenly afterlife, that changed in a big way during the plague. People buried their own loved ones, walked past piles of corpses, and looked for almost inevitable signs of infection in themselves. Death literally moved among them.

Art began to reflect that, and while it's morbid at a glance, it's also a pragmatic reminder that things like social standing and wealth don't mean a thing in the end: Death waits for us all.

Thousands of Jews were slaughtered in an attempt to stop the plague

The Holocaust remains one of the worst genocides in history, but Europe's Jewish population was targeted with widespread slaughter centuries before the Third Reich rose to power. When the Black Death swept across countries and killed wholesale throughout the 14th century, people wanted answers. Rumors started circulating that the plague was a punishment from God, delivered on a population that had allowed Muslims and Jews to continue to live among them. (The real reason Jewish communities had a lower death rate from the plague were their strict religious guidelines regarding hand-washing, bathing, burials, and sanitation.)

As if that wasn't bad enough, some Jewish communities — particularly in Germany and France — were accused of actively trying to spread the plague to Christians, and the idea that conspirators were poisoning wells and other sources of drinking water spread. The fallout was shocking stuff.

Instances of the wholesale slaughter of entire Jewish communities kicked off across Europe. More than 6,000 people died during one conflict in Mainz, and 2,000 Jewish people were burned alive in Strasbourg. Between 1349 and 1350, nearly all Jews were either killed or forced out of England, Germany, and France. Hundreds of Jewish communities were destroyed, and by 1400, the 19,000-strong Jewish population of Frankfurt had been reduced to just 10.

Traveling flagellants sang and practiced self-harm in public to appease God

Desperate times call for desperate measures, and it's difficult to imagine the horror that unfolded as the Black Death spread to become one of the worst outbreaks in history. It's human nature to try to figure out why something happens, and at the time, many believed that people were being killed — horribly and en masse — by a God who was angry about... something. One major movement took to trying to appeal to God for mercy by shedding their own blood, and the flagellants became known for their public displays of self-harm and bloodshed.

They believed their sacrifice was a blood sacrifice akin to Christ's, and that it would surely demonstrate how sorry they were for their failings that had brought this terrible, relentless illness. Flagellants had already been around for some time by the height of the Black Death — the movement was first inspired in 1260 by an Italian hermit who had reportedly gotten directions from the Virgin Mary herself — but it was during the 14th century that communities of flagellants traveled Europe to hold public displays of ritualistic self-flogging and singing.

Flagellants dressed in white robes would strip to the waist, kneel, and beat themselves while others sang songs that became known in Germany as Geisslerlieder, or "flagellant songs." Lyrics included this one from the "Song of the Flagellants During the Time of Plague": "Now here comes the wave of evil; flee from hot hell. Lucifer is an evil companion. Whomever he catches, he smears with pitch. Therefore, we intend to flee him."

The Black Death may have triggered the Little Ice Age

In 1709, Europe was devastated by a deadly frost that remains largely a mystery today. Temperatures plummeted to well below freezing overnight, and it was one particularly devastating incident in a larger, centuries-long period of cold weather that's been dubbed the Little Ice Age. It's sometimes said to be applied to the period between 1500 and 1850, although some researchers add a century or two on the beginning of that. It was marked by lower-than-normal temperatures, freezing rivers — including the Thames — and mass starvation. There's been all kinds of theories about what caused the Little Ice Age, but it seems perhaps most likely that it was a perfect storm of conditions that included volcanic eruptions and the Black Death.

That's the theory put forward by a research team from Utrecht University in the Netherlands (via the BBC). They examined lake-bed sediment to examine the historical records preserved there, and they found that data — particularly that extrapolated from pollen grains and leaves — suggest that around 1347, there was a massive dip in cereal grains. 1347, of course, marks the beginning of the spread of the Black Death, so what's the connection?

They believe that as the Black Death spread, crops went unharvested then unplanted, farms went untended, and agricultural land ultimately returned to nature. Reforestation happened on such a large scale that more carbon dioxide was absorbed from the atmosphere, helping to lower the temperature and kicking off what would become a centuries-long cold spell.

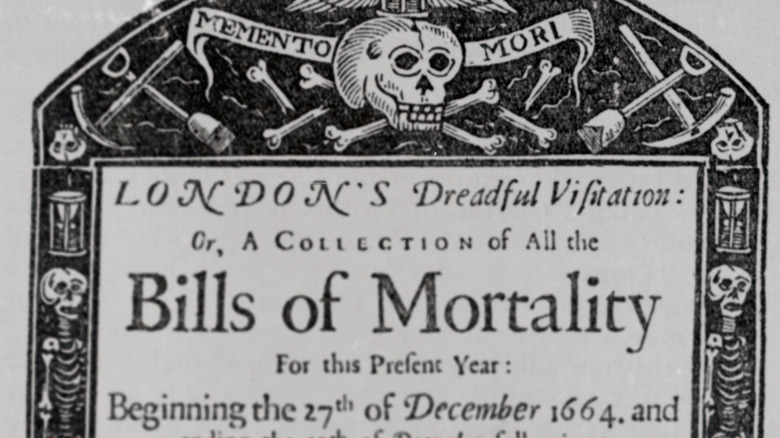

It gave rise to the searchers

When the Black Death reemerged in the mid-17th century, the status quo was shattered into about a million tiny pieces. Take London: Those who could flee, did so. Those who were left had to fend for themselves, even when it came to medical treatment and the recording and reporting of deaths. That still needed to happen, and was more important than ever. The era's Bills of Mortality remain some of the most detailed records of plague deaths in London, and they were made possible by a group of women called the searchers.

The position of searcher was a formal one, and each London parish would essentially employ a pair of women to not only collect the bodies of the dead, but to do an examination and determination of the cause of death. (It's unclear just when the first searchers were hired, but it seems to have been an official profession from about the 1530s.) Eerily, official laws governing the searchers stressed that while they were employed, they were forbidden from other work: There was a likelihood that they would contract the plague themselves. Bribery wasn't uncommon — especially considering that a ruling of plague would result in quarantining entire homes and families.

All the information gathered by the searchers would pass through a few different people and ultimately be published in a weekly record known as the Bills of Mortality. In 1665, at least 70% of the city's recorded deaths were attributed to the plague.

It may have been responsible for the disappearance of Greenland's Viking colonies

It's safe to say that the world is still fascinated by the Vikings, even as we continue to dig up ever-more-disturbing details about their raiding practices. Strangely, it turns out that the Black Death may have played a big part in the downfall of the Vikings.

Greenland was a Viking stronghold for several centuries, starting in around 985. Viking presence there grew to several settlements around 12 churches, and just what happened to them, no one's ever been sure. They started to decline by the end of the 14th century, and by the middle of the 15th, it seems as though everyone was just... gone.

The running theory hinges on two things, and interestingly, the Black Death is involved in both of them. For starters, it seems as though the Little Ice Age changed the area's climate so that, not only were the Vikings unable to raise livestock and farm, but the waters around Greenland also became dangerous. That shut them off from fishing stocks and made it harder to receive and ship goods, including walrus ivory, one of their most lucrative exports. (That said, there wasn't much call for it anymore, since elephant ivory was all the rage.) The Black Death devastated the Norwegian city of Bergen, an important port for ships traveling to and from Greenland, when an English ship carrying the plague ran aground there in 1349. In addition to carrying the Black Death, it effectively severed any ties that may have been able to save Greenland's Viking settlements.

It's been weaponized into germ warfare

Have people made it a point to spread the plague on purpose? Of course they have. In a study published in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases, the University of California, Davis, confirms that the story about the plague initially spreading to Europe after contagious corpses were weaponized and hurled into the Crimean city of Caffa is entirely plausible. Have we learned a very important lesson? Nah.

Fast forward to World War II, and Japan's absolutely terrifying biological warfare project. It was known as Unit 731, and the scientists involved used sites across China in biological warfare experiments. Hundreds of thousands of people sickened by experiments like the one that kicked off in October of 1940. That's when plague-infested rats and fleas were released into Ningbo and Quzhou.

Surely, we learned... right? Nope! During the Cold War, both the U.S. and the USSR experimented with weaponizing the plague. Evidence of the Soviet program still exists in the form of Vozrozhdeniya Island, a place that's so toxic that it should definitely be off-limits for at least the next... forever and a day. It was the site of experiments in biological warfare, and some of those weapons have escaped. In 1972, the plague-infested corpses of two fishermen were recovered from the area, and when the BBC did a deep dive into the shady history of the place, they reported stories of "a living nightmare, where anthrax, smallpox, and the plague hung in great clouds over the land."

Those weird, weird sexually explicit keepsakes from the Middle Ages probably had something to do with the Black Death

Anyone who follows any history pages on social media has probably seen the images of admittedly strange — and X-rated — metal badges depicting human genitalia. Sometimes those genitalia have wings, sometimes they're on boats or on horseback, and sometimes they're being carried on the shoulders of people who seem to be participating in some kind of parade. Weird? Absolutely.

The badges coincided with one of the most brutal outbreaks of the Black Death, and many were made starting around 1350. At the time, saints who were believed to bestow protection against the plague and illness were all the rage, and honored with not only parades and processions, but also pilgrimages and special masses. Badges were likely handed out at such events, and medieval folklorist Malcolm Jones explains (via Atlas Obscura), "by the exposure of the genital icon, whether male or female, they were intended to disarm that ever present yet vague malevolence known as the Evil Eye."

Research done by Lena Mackenzie Gimbel for the University of Louisville supports this theory, and found the phenomenon has been largely uninvestigated and written off as bizarrely vulgar when it was, in fact, the precise opposite. Well into the 17th century, there was a persistent theory that the plague was spread via eye contact, so it makes sense that these badges might have acted as a protective talisman by giving potentially infected people something interesting to look at. Desperate times, as they say.