Things You Get Wrong About The Last Supper

It's easy to debate the historicity of Jesus and the Disciples as well as the veracity of biblical accounts concerning the Last Supper, that last convening of Jesus and his 12 closest followers. And indeed, people have spent years doing so, but there are still a number of common misconceptions about the Last Supper itself. Because whether you're a diehard Christian, avowed atheist, Zoroastrian, or anything else, you probably have a few ideas about what took place at the Last Supper — whether you take it as fact or legend or a blending of the two — and chances are several things you think about this famed, fateful meal are wrong.

What can be said for certain about the Last Supper is that certain basic facts are hard to come by. For example, according to Live Science, while scholars are fairly certain the event took place in early April, it's a little harder to pin down the year: it may have happened any year between 26 and 36 A.D., based on the known tenure of Pontius Pilate as Roman procurator of Judea. There's also the question of where this most famous meal took place. Many Christians believe it took place at a holy site in Jerusalem, called the Cenacle, above what's believed to be the burial place of King David, but according to Bible History Daily, no concrete archeological evidence has ever been found to back this up. So 2,000 years later, everyone is left to wonder about it.

The Last Supper was a seder

According to Britannica, here's the definition of a seder: "a religious meal served in Jewish homes on the 15th and 16th of the month of Nisan to commence the festival of Passover (Pesaḥ)." Given that Jesus and his followers had come to Jerusalem to celebrate Passover, according to The Wall Street Journal, and given the fact that Passover, Good Friday, and Easter are always close together on our modern calendars, it's entirely understandable why most people assume the Last Supper, which is also often called the Lord's Supper, was a traditional Passover seder.

It's more likely, though, that the timing of the Last Supper ended up being coincidental relative to Passover, according to The Washington Post. While Passover was of course already observed by the time of Jesus and his disciples, its celebration usually involved little more than eating a single sacrificed lamb, not having a larger and ritualized meal. The seder such as it's known today was unlikely to have been practiced at the time of Jesus' death, so it's much more likely that the Last Supper was just a meal, the significance of which would come later and would resonate for Christians, not for practitioners of Judaism.

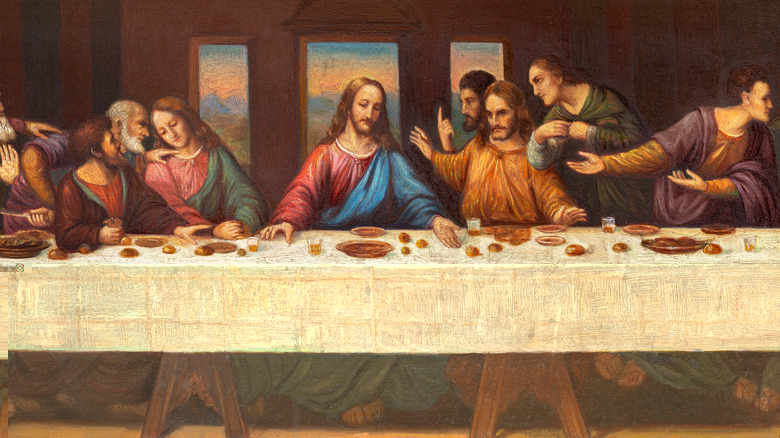

There would have been a table at the Last Supper

In almost every depiction of the Lord's Supper, from that most famous work by Leonardo Da Vinci to a sketch in the Mel Brooks movie "History of the World," Christ and his followers are shown sitting around a large table as they eat their final fabled meal. But it's almost a certainty that a meal of this kind would not have been eaten at a table such as is always shown. According to reporting in Live Science, meals such as the Last Supper would have been eaten seated on cushions on the floor.

This was how meals were eaten at the time in Palestine, not to mention the way meals were eaten throughout much of the larger Roman world as well. While it's possible there would have been a low table around which those assembled could have gathered, there would certainly not have been a "table height" piece of furniture surrounded by chairs or benches; the floor still would have been the seat, with a cushion or carpet used for seating. And it's much more likely that each man would have sat on his own cushion and eaten off of stone plates. Certainly there would not have been a large wooden table complete with a table cloth, as is so common in paintings of the meal and so oft recreated on altars in churches the world over.

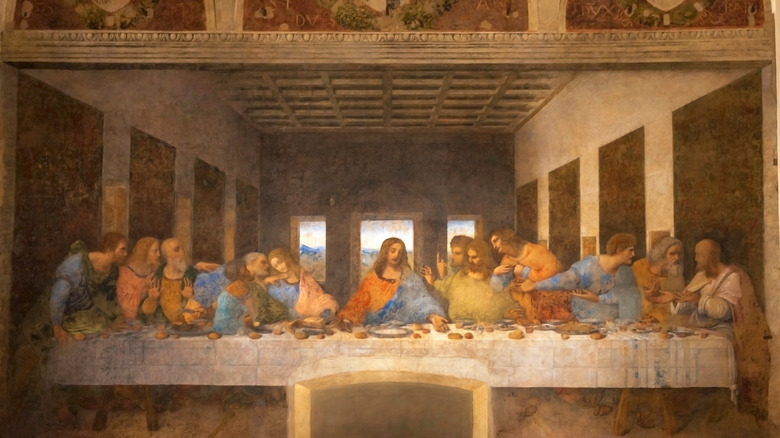

Da Vinci's painting is a true fresco

As it turns out, simply applying paint to a plaster wall does not a fresco make. In the case of arguably Leonardo Da Vinci's second most famous painting (the diminutive and enigmatic Mona Lisa being his most well known work, according to Art Hive), "The Last Supper," is no fresco at all. Why? Because according to the art experts from My Modern Met, a true "buon fresco" involves the use of paints applied to wet plaster. This fresco painting technique ensures the lasting quality of the artwork as the paints seep into the wall material, bonding closely with the plaster and ensuring lasting looks.

But for "The Last Supper," Da Vinci went with the "secco fresco" method of painting, which involved painting with tempera paints onto dry plaster. The secco technique afforded Da Vinci two advantages: one, he could work at his own pace on his own schedule, not harried by the drying plaster — it's well-known Da Vinci was a habitual procrastinator, so it makes sense he would be taken with the added flexibility of a secco fresco approach. Second, as he was not rushed by a drying wall, Da Vinci could do something else for which he is also known: he could carefully, masterfully apply the style and detail that set his work above almost all else from his or any era. In "The Last Supper," Da Vinci used chiaroscuro and sfumato painting techniques to enhance the contrast and color, and he used a nail and strings (via "Best of Italy") to help him master the perspective and vanishing point that anchors it.

Mary Magdalene was present at the Last Supper

There is a common misconception, oft repeated, that Mary Magdalene was present at the Last Supper, but as far as we know, it was only Jesus and his 12 disciples. According to TIME, Mary Magdalene is not mentioned as being present at the Lord's Supper (and indeed a reading of the gospel accounts of the event supports this, per ThoughtCo). So why do so many people think this controversial biblical figure — remember, by varying accounts Magdalene was a sex worker, the wife of Jesus, a faithful disciple, or somewhere in between — was there at the table? (Not that there was a table at all.)

The confusion can be traced primarily to the most famous rendition of the Last Supper, Da Vinci's secco fresco painted on the wall of the dining room in the Santa Maria della Grazie convent, per the Milan Museum. The figure immediately at the right hand of Jesus (meaning to the left when you're looking at the painting) is often thought to be a woman, and to be Mary Magdalene specifically. But according to My Modern Met, that is in fact the Apostle John. Shown without a beard, with the long hair common on men at the time, and indeed with an effeminate look, the misinterpretation is understandable, but that's John, not Mary or any other woman, none of which were likely present.

The painting you see today is by Da Vinci

When you visit the former convent called Santa Maria della Grazie today and look up at the magisterial 29-foot-wide, 15-foot-tall painting of "The Last Supper" by Leonardo Da Vinci, you are not really looking at a painting by Da Vinci at all, in a certain sense. According to My Modern Met, that same secco fresco technique the master artist used that allowed him to take his time and ply his techniques also destined his painting to damage. This type of fresco painting is terribly delicate, and within less than two decades after the completion of the painting in 1498, pieces of paint were already flaking away and the quality of the image was failing.

"The Last Supper" has undergone so many restorations over the years that it's not likely it features more than a precious few of the Da Vinci's own original strokes of the brush (via The Art Newspaper). So what we see today is more like the work of other artists doing their best not to undo the work of the Renaissance master, but not his own actual painting. Still, the composition, the perspective, the scale, and the spirit of the painting are all Leonardo's, if not the actual top layer of paint these days. And indeed even in the time of Leonardo and the other Renaissance masters, it was not uncommon for many people to work on large pieces of art without getting credit.

The Gospels are the Bible's first mention of the Last Supper

According to Britannica, there are 27 books that make up the New Testament of the Bible, the first four being the Gospels (according to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John), then the Acts of the Apostles, the Letter of Paul to the Romans, then, seventh, the first Letter of Paul to the Corinthians. Given that the gospels are positioned first in the book and that they are the story of Jesus, it makes sense to assume that they are the first — and potentially the only — source material we have on the Last Supper.

But that's not the case. Per Bible Gateway's text of the King James Bible, in 1 Corinthians 11, verses 23 through 26, Paul wrote: "For I have received of the Lord that which also I delivered unto you, that the Lord Jesus the same night in which he was betrayed took bread. And when he had given thanks, he brake it, and said, 'Take, eat: this is my body, which is broken for you: this do in remembrance of me.' After the same manner also he took the cup, when he had supped, saying, 'This cup is the new testament in my blood: this do ye, as oft as ye drink it, in remembrance of me.'"

Now, why is that of special note? Because according to PBS, the first of the Gospels, that of Mark, was written in about the year 70 A.D. But the first letter to the Corinthians was written nearly two decades earlier, per Britannica, likely in 53 or 54 A.D.

The story of the Last Supper is the same in all the Gospels

There are four accepted gospels in the Christian Bible, though others remain outside official church canon, such as the Gospel of Thomas, according to PBS Frontline. Given that the Bible includes the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John and that these books all tell the same story, namely of the life and acts of Jesus Christ, it's natural to assume that they are all on the same page, as it were, when it comes to the details of the Last Supper. But they're not. As is often the case among the Gospels, the books of Matthew, Mark, and Luke differ markedly from the Gospel of John when it comes to the Lord's Supper. Those first three books, often known as the Synoptic Gospels per Britannica, contain details that are quite similar and often use matching language in their accounts.

As shared in a Frontline penned by an expert in classics and religious studies, one of the largest discrepancies between the Gospel of John (the Spiritual Gospel, as it is often called) and the Synoptic Gospels is the very date of the Last Supper. Whereas Matthew, Mark, and Luke place the meal during Passover, John places the Last Supper before the start of Passover, lending further credence to the unlikelihood of it having been a seder (via the Washington Post). And further, this places the day of Jesus' execution on the same day as lambs would have been slaughtered all around Jerusalem, which forces us to equate his crucifixion with the sacrifice of thousands of innocent animals.

The Last Supper was a reverent occasion

Hardly the staid, reverent occasion one might expect from having seen a communion ceremony performed in a church, the Last Supper was anything but a calm and peaceable affair, and this can be sourced right to the Holy Bible itself. In fact, the revered, seemingly blameless disciples (soon to be Christian saints) at the dinner argued with one another over which of them was the greatest, according to Bible.org. Reading the Gospel of Luke in particular reveals how the dinner devolved into an argument, with one verse reading: "However, there also arose a heated dispute among them over which one of them was considered to be the greatest" (via the official Jehovah's Witness site).

And then later, even though Jesus had asked his disciples to stay up and stay vigilant as he went out into a garden near the room where they all had dined, his followers end up falling asleep. The Gospel of Luke says: "When [Jesus] rose from prayer and went to the disciples, he found them slumbering, exhausted from grief." Or were they possibly exhausted from heavy eating and drinking? Either way, Jesus remonstrates his disciples and tells them to wake up and keep praying, as the fateful hour is close at hand.

Jesus was asking for his disciples to remember him

There is a common and potentially major misconception as to the meaning of some of Christ's most famous words of all time, according to Core Christianity. Those words are: "Do this in remembrance of me." A casual reading of the biblical text or participation in a Eucharist ritual would make one think Jesus was telling his followers to break bread and drink wine to help them remember him, their messiah. But that's not what he meant — not likely, anyway, when you take into account many instances in the Old Testament in which offerings and rituals and sacrifices and such were actually intended to help the faithful be remembered by their god.

When Jesus tells his disciples to begin practicing the Eucharist, what he is telling them to do is perform an act that will help them present themselves before god, not an act that will help them remember Jesus. Ultimately, it's a totally different message, and one that rather makes sense: A mere mortal human needs to put in the effort in to show themselves worthy and faithful before God, and if blowing trumpets and making burnt offerings was the go-to pre-Jesus, bread and wine are the go-to post.

Only da Vinci depicted the Last Supper

If you close your eyes and picture a painting of the Last Supper, it's an almost sure bet you'll be seeing that fresco (well, fresco secco) painted by Leonardo Da Vinci in the late 1490s in the Santa Maria della Grazie convent. But Da Vinci's Last Supper rendition was hardly the first or the last major work to capture this major event. Forerunner to the high Renaissance artwork that would come, Giotto painted a Last Supper scene in the early 14th century, likely in 1304 or 1305 according to The History of Art. His painting, which predates Da Vinci's by nearly 200 years, depicts the 12 apostles and Jesus around a table without food visible.

About 650 years later, Salvador Dalí painted an ethereal, haunting take on the scene titled "The Sacrament of the Last Supper," according to the National Gallery of Art. His 1955 work of oil on canvas depicts a simple table, with only wine and bread served, and with a figure floating above the scene, arms outstretched, calling the mind to the coming crucifixion. Between Giotto and Dalí, there are plenty of other notable works depicting the scene, including those by famed artists like Fra Angelico, Jacopo Bassano, and others.