Details About The Golden Age Of Rap That Didn't Happen Like You Think

Before rap rose to become a dominant form of popular music, the genre had just a few kinks to work out. For example, while the whole Hip-Hop scene really started cooking in the early '70s, rap didn't exist as a recorded form until 1979. Early tracks were basically disco songs with dudes rapping over them. Some of the brightest early stars of the genre quickly faded away while bit players rose to prominence, and when rap started to snowball in popularity, it stubbornly refused to become the throwaway fad that practically every music journalist proclaimed it to be.

This is to say that, unless you happened to be around at the time, you may have a slight misconception of just how the musical genre that the kids call "Hip-Hop" became the force that it is. (Side note: Hip-Hop is actually an entire culture. Rap is the music of that culture. We didn't make the rules, but we do obey them.) Well, we are what the kids call "geeks," meaning that we know a lot of stuff — and we're here to fill in some of the key details about rap's early days that didn't happen quite like you think.

The first rap song wasn't Rapper's Delight

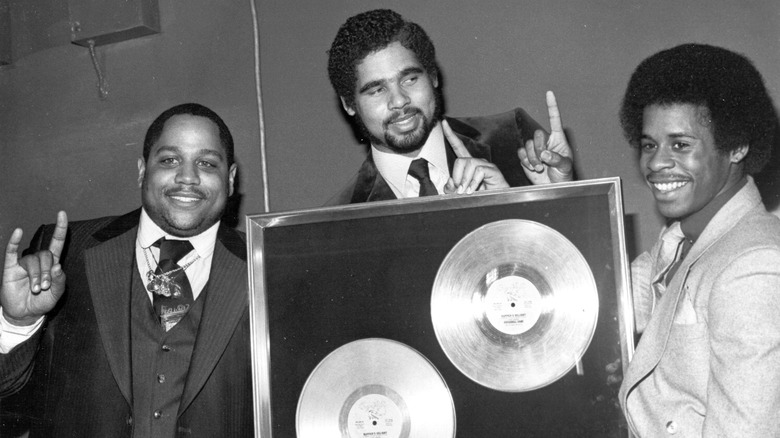

Ask any rap-head — as they preferred to be called — what the first rap record was, and you'll get the same answer ninety-nine times out of a hundred: "Rapper's Delight" by the Sugarhill Gang. A bunch of interlopers from New Jersey who were assembled specifically for the purpose by Sugarhill Records founder Sylvia Robinson, the Gang — Michael "Wonder Mike" Wright, Guy "Master Gee" O'Brien, and Henry "Big Bank Hank" Jackson — blew Hip-Hoppers' minds with the release, but caught plenty of flak from their fellow rappers. Specifically, they were... well, outsiders from New Jersey that nobody had ever heard of, and Hank cribbed all of his rhymes from his friend Grandmaster Caz of the Cold Crush Brothers, a well-respected crew who were actually from New York.

The Cold Crush, along with such stars as Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five (via the Guardian), were among many who had been kicking around the idea of making an actual record for a while — too long, as it turned out, for Sugarhill beat them all to the punch. Well, almost. Practically lost to history is the fact that popular funk outfit The Fatback Band, accompanied by radio DJ Tim Washington on vocals, had actually beaten "Rapper's Delight" to record store shelves by a full six months with their tune "King Tim III (Personality Jock)," as reported by the Fayetteville Observer. The track was released as the B-Side to the band's single "You're My Candy Sweet," because their label just didn't think this rapping stuff was going to catch on with listeners, which allowed the Sugarhill Gang to grab credit where it wasn't exactly due. Flash and others would quickly follow, and it wasn't long before major labels began to take notice.

The first artist signed to a major label isn't who you think

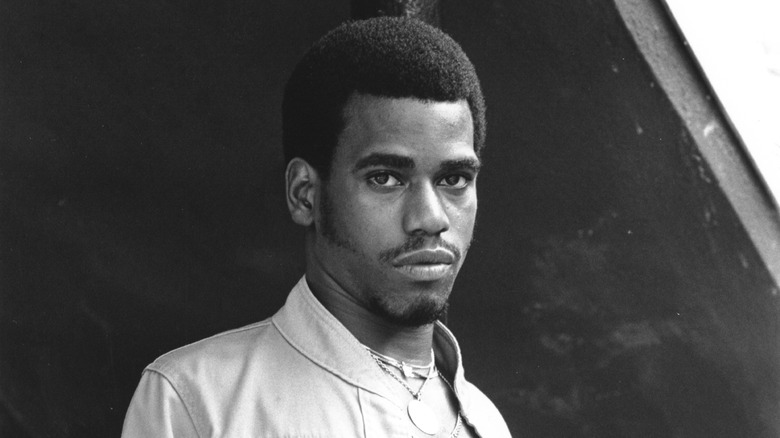

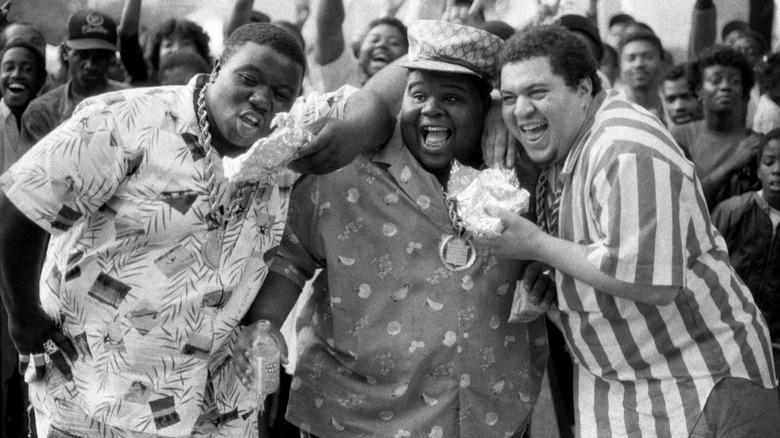

It wasn't Flash, Caz, or any of those fellas who were the first to get one of those majors into a signin' mood, however — nor was it the Beastie Boys or Run-D.M.C., whom you may think of as being the first truly popular rap artists. Rather, it was Kurtis Walker, professionally known as Kurtis Blow, a charismatic and talented MC who made his bones in Hip-Hop as a breakdancer and DJ in the early '70s, according to Billboard. At the suggestion of future mogul Russell Simmons, the golden-voiced Walker adopted his stage moniker and became a full-time rapper in 1977, often accompanied by Simmons' younger brother Joseph, who at the time went by the stage name "DJ Runnin' Things." Such was Walker's musical acumen (he could play piano, and showed a natural affinity for the recording studio) that he was signed to Mercury in 1979 at the age of 20 — a partnership that proved fruitful, and led to a string of firsts for rap.

Not only was Walker the genre's first major-label signing, but he also fielded its first gold single ("The Breaks," 1980), embarked on its first national tour, signed its first endorsement deal, and became the first MC to perform at New York's iconic Madison Square Garden, opening for the Commodores and Bob Marley in 1980 (via Tennessee Tribune). He would go on to produce records for the likes of the Fat Boys and legendary MC Lovebug Starski — and his mentorship proved especially beneficial to Joseph Simmons. After deciding to become an MC himself, young Joe briefly adopted the stage name "Son of Kurtis Blow" before settling on a shortened version of his initial moniker, "DJ Run," and forming the aforementioned Queens trio Run-D.M.C.

Rap battles weren't always so personal

When most people think of rap battles, they think of Eminem ridiculing rivals in exceedingly clever fashion until they just go home. But in rap's early days, "battles" were more like contests to see who could pump up the crowd the most. However, that went out the window one infamous night in 1981 at the Harlem World nightclub, when MC Kool Moe Dee of the Treacherous Three, a razor-tongued rapper with a voice and vocabulary to match, decided that the reigning champ had gotten too big for his britches.

Moe Dee's victim that night was his friend, MC "Chief Rocker" Busy Bee, whose call-and-response routines and funky scatting never failed to hype up the crowd. As related by the MCs themselves in the rap documentary "Beef," Moe Dee was actually hosting that evening's MC contest, but he became a little peeved when Busy Bee entered the venue already running his mouth about how whoever was running this joint ought to just give him the trophy. Indeed, by all accounts, he rocked the crowd and would have won — if Moe Dee had not put himself on the list to follow the "champ." On the bootleg tapes that would eventually be heard bumping out of cars and boom boxes across the five boroughs, jaws could be heard hitting the floor from the moment Moe Dee uttered his first rhymes: "Now come on Busy Bee, I don't mean to be bold / But put that bomp-bitty-bomp bulls*** on hold / We gonna get right down to the nitty-grit / I'mma tell you a little something why you ain't s***." Moe's verbal assault was overwhelming — and when those tapes hit the street, every rapper in New York realized that their craft had changed drastically in that one night.

The Beastie Boys didn't start as a rap group

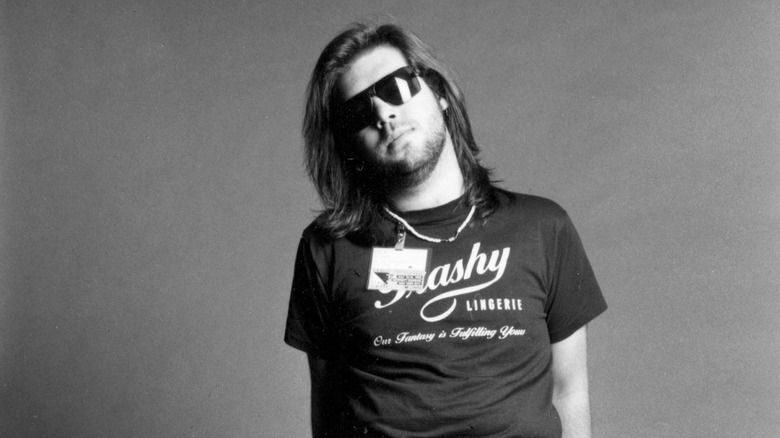

One could be forgiven for thinking that the Beastie Boys (Michael "Mike D" Diamond, Adam "MCA" Yauch, and Adam "King Ad Rock" Horovitz) must have come out of the womb spouting weird rhymes over killer tracks. Although their massive 1986 debut album "Licensed to Ill" wasn't exactly lyrically mind-blowing, it was sonically interesting, and the Beasties' later work — particularly 1989's groundbreaking sample-fest "Paul's Boutique" — would rather improbably cement them as one of the more creative, artistic groups in all of rap. Before all of that, the Boys' musical ambitions had nothing to do with art rap, or rap in general; they began as a hardcore punk band called the Young Aborigines, with Diamond on drums and Yauch on bass (via Exclaim).

The band eventually poached guitarist Horovitz from fellow punk band The Young and the Useless, and the three began incorporating elements of rap into their music after discovering they had a shared love of the Furious Five and Sugarhill Gang. In 1984, their mutual pal Rick Rubin — who had begun serving as a DJ at the newly-christened Beasties' shows — started a small record label out of his NYU dorm and was soon joined by Russell Simmons, with Simmons bringing little brother Joe's Run-D.M.C. to the table, and Rubin bringing the Beastie Boys. Now, we wouldn't ordinarily recommend signing your life away to a shaggy-haired college kid who spends all day calling up record shops from the top bunk of his sweaty dorm room, but in the Beasties' case, it worked out pretty well.

One of rap's biggest labels didn't start that way

That small, crappy label: Def Jam Recordings, which would go on to become a rap powerhouse in a ridiculously short amount of time. After first releasing a little-heard EP from Rubin's punk band Hose, the label began to focus on rap singles. According to an interview with Sirius XM, it was Ad Rock who, while sifting through a pile of demos Rubin had received that same year, happened upon a submission from a 16-year old kid by the name of James Todd Smith. Rubin promptly signed the dynamic youngster, .and a reworked version of the demo tune became Def Jam's first rap twelve-inch: "I Need a Beat," by the newly-christened LL Cool J.

More singles followed, including the classic "It's Yours" by New York rap duo T La Rock and Jazzy Jay, and "Rock Hard," the Beasties' first recording with the label, in 1984. While Run-D.M.C. had amicably departed for Profile Records, the massive success of LL's 1985 debut album "Radio" ensured that they weren't missed too much — and their short time at Def Jam resulted in a close association with the Beastie Boys that would last through both bands' most fruitful periods. Run and D contributed two songs ("Slow and Low" and "Paul Revere") to "Licensed to Ill," and in 1987, the bands embarked on a worldwide tour together while at the height of their respective powers.

The term Hip-Hop didn't come out of nowhere

While the phrase "Hip-Hop" appeared within the first line of "Rapper's Delight," it didn't just tumble out of Wonder Mike's mouth. Up until a certain point, the movement that had been brewing for years in the clubs and parks of New York hadn't really had a name; people would head out to go to the "jam," or the "get down." That changed in one night, with one party, at which one MC came up with a novel way to make fun of his friend Billy.

In an interview with noted Hip-Hop historian Steven Hager, Busy Bee, who was present at the party, described how the whole shindig was thrown in honor of his buddy Billy, who was about to leave to join the Army. The dude also happened to be friends with Grandmaster Flash and his (at the time) three MCs, and as Flash spun that night, MC duties were mainly being handled by the late, great Keith "Cowboy" Wiggins. According to Busy Bee, Cowboy would periodically get on the mic to shout out Billy, throwing in a rhythmic chant mocking the cadence of marching soldiers: "Left... right... left... right... hip... hop... you don't stop!" This must have struck a major chord with the crowd, because the next day, everybody was referring to the party as a "Hip-Hop jam," and the phrase just stuck from then on.

It wasn't Rick Rubin's idea to fuse rap with rock

By the early-to-mid '80s, Disco had pretty much ceased to be a factor in pop music. While some of the crews were clinging to uptempo, funky party tracks in their recordings, a contingent of youngsters were doing things a bit differently — and leading this pack was Run-D.M.C. Their 1983 single "It's Like That/Sucker M.C.s" featured the group's two rappers trading near-shouted rhymes over huge, sparse drum beats, and by the time their self-titled debut album dropped the following year, another interesting element had been added: electric guitars.

Of course,the group would later drop-kick rap into the mainstream with their landmark Aerosmith collaboration "Walk This Way," and one could be forgiven for thinking that the tune's co-producer Rick Rubin was also responsible for their early rock-rap missives such as "Rock Box" and "King of Rock." That credit actually belongs entirely to Larry Smith, an old-school session musician who got his foot in the Hip-Hop door playing bass on Kurtis Blow's "Christmas Rappin'." According to an in-depth piece by music journalist Robbie Ettelson for Medium, Blow helped steer Smith toward production, a role in which Smith pioneered the application of big, booming, rock-style drum sounds to rap. Smith produced two albums apiece for Run-D.M.C. and legendary group Whodini, applying an R&B sheen to the latter and a hard rock edge to the former, with sterling results in the form of two gold and two platinum platters. Smith, unfortunately, passed away in 2014, and while he's not exactly a household name today, he's an icon in the world of rap.

The invention of beat boxing wasn't exactly collaborative

Ever since there have been babies, people have been making percussive sounds with their mouths. But the art of beat boxing — so named because its first practitioners vocally imitated the sounds of early drum machines, or "beat boxes" — has always gone a bit beyond blowing raspberries. Today's beat boxers can perform multi-part compositions, leaving spectators in awe of the level of control they have over what must be seven or eight sets of vocal cords. Howver, in the early '80s, the technique's innovators blew crowds' minds simply by laying down hot drums with their pieholes — and those innovators, who gave birth to the form as we know it, numbered all of two.

They were: Douglas "Doug E. Fresh" Davis, a brilliant MC who billed himself as "The Original Human Beat Box" and claims to have invented the technique due to his background as a trumpet player (via Okayplayer), and Fat Boys DJ Darren "DJ Doc Nice" Wembley, who billed himself simply as "The Human Beat Box" (via the Los Angeles Times). As one might imagine, there was a bit of a rivalry between the two, and their styles were quite different. Wembley's was more aggressive and heavy while Davis' had a bit more complexity and finesse, a difference which Davis hilariously pointed out on Doug E. Fresh and the Get Fresh Crew's massive 1985 single "The Show." Their combined innovations inspired countless beat boxers to push the form ever further, beginning with such greats as former Roots member Rahzel, who can somehow rap and beat box simultaneously.

The evolution of the modern rap flow happened more quickly than you think

It may seem like during the '90s, rap flows just got trickier and more complex year after year, from groups like the Pharcyde early in the decade, on through to tongue-twisting maestros like OutKast and Eminem in its later years. While this isn't wholly inaccurate, all of those artists followed a blueprint that came into existence quite suddenly thanks to ... well, basically, a couple of dudes who thought they were better than all the rest of the MCs. As it turned out, they were right.

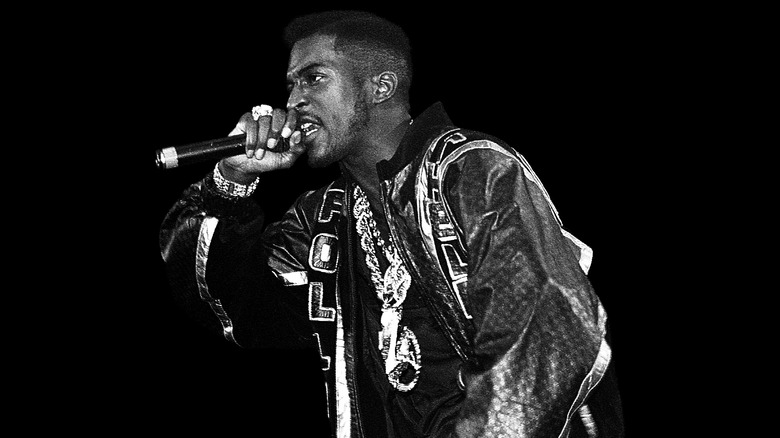

Before 1986, rap flow was very simple rhythmically and poetically, with monosyllabic rhymes dropped on or about the final downbeat of every measure. That came to a crashing halt with the release of two records that year: "Criminal Minded," the debut album from Bronx crew Boogie Down Productions and its prodigiously gifted MC KRS-One, and the single "My Melody/Eric B. is President" by Eric B. and Rakim. Rappers and listeners alike had never heard anything quite like the rapid-fire, machine-gun flow of BDP's album opener "Poetry," nor the complex, internal and multisyllabic rhyme schemes of Rakim, which he delivered with a disarmingly relaxed flow that many critics have noted resembles a jazz saxophonist (via Complex). In the years immediately following, rappers like Juice Crew members Kool G Rap and Big Daddy Kane would follow their lead, in turn influencing all of those wordsmiths of the mid-to-late '90s. But, as Kane himself made clear in an interview with radio station Power 105.1, the "top three rappers" of his era were KRS, Rakim — and himself, of course.

The evolution of scratching also happened rapidly

Yes, 1986 was a banner year for the modern style of MCing, and the following year, it was the DJ's turn. Before 1987, scratching tended to sound a bit clunky, due to the fact that the crossfaders — switches built into DJ mixers that allow the performer to switch between turntables, or play both at the same time — which were in use during that time just didn't sound terribly clean. A new technique emerged that year, one which substituted a simple momentary button for a fader; the turntable would be muted when the button was out, and would play when the button was pushed. Rhythmically tapping the button while moving the record produced a crisp, mind-bending sound reminiscent of, say, Optimus Prime turning from a truck into a robot — hence, the technique came to be known as the "transform scratch."

According to Philadelphia Magazine, the great DJ Jazzy Jeff pioneered the technique, debuting it on the song "The Magnificent Jazzy Jeff" from the 1987 Jazzy Jeff and the Fresh Prince album "Rock the House." While he certainly deserves credit, two other legends were parsing out the technique during roughly the same period: wickedly skilled DJ Mixmaster Ice of UTFO, who used the transform on that group's 1987 album "Lethal," and none other than Grandmaster Flash, who employed it on the 1988 Furious Five reunion album "On the Strength." Flash even partnered with audio hardware company Gemini to produce a commercial device called the FlashFormer, but it didn't take off — likely because the innovation represented by the transform scratch was so profound that DJ mixer manufacturers almost immediately began retooling their fader designs to make them capable of mimicking momentary buttons.

The genre's first genius producer isn't who you think

While producers like Larry Brown and Rick Rubin were using their musical influences to open up rap's sonic template, and Queens producer Marley Marl was innovating with his use of sampled drums, a true wunderkind of rap production was laboring away in his bedroom at his mother's house, mastering a piece of equipment that would soon become a vital tool of the trade. Paul McKasty, who was drawn to rap after a short stint in pop/rock group Mandolindley Road Show, had a notion that one might beef up the sound of the rap tracks he was hearing by incorporating more organic sounds. To this end, he began studying the E-mu SP-12 sampler, one of the cheapest, most accessible devices of its kind.

According to a retrospective by Gino Sorcinelli for Medium, Paul's deep musical knowledge combined with his understanding of the E-mu device and its strengths and limitations made even his early efforts at rap production sound like nothing that had come before them — gritty, jittery, and textured. Those early bedroom studio tracks caught the attention of local rappers the Clientele Brothers, who in turn introduced Paul to rapper Mikey D, who extended an invitation for Paul to join his group the L.A. Posse. After taking up residence at Queens recording studio 1212, Paul would share his knowledge of the sampler with such future luminaries as Main Source MC and producer Large Professor and Ced Gee of Ultramagnetic MCs, who would benefit from Paul's production on their landmark album "Critical Beatdown." Unfortunately, he would never get the credit he deserved. After an all-night studio session with rap group Almighty RSO one summer night in 1989, Paul was shot to death in his mother's home at the age of 24. The murder has never been solved.

Gangsta rap didn't originate how you think it did

Rap started to get all gangster-y around 1988, with the advent of crews such as N.W.A. and Above the Law. It took one record to basically set the aesthetic for the entire genre of gangsta rap: Ice-T's "6 'N The Mornin'," from 1987, on which the rapper spun an epic street narrative spanning roughly a decade over the most sparse and rugged of beats. The song is rightly credited with giving birth to gangsta rap near-fully formed, and on his 1991 song "O.G. Original Gangsta," Ice described how it came to him in a burst of inspiration when he realized that rhyming about rocking the party wasn't really getting him anywhere on the L.A. rap scene. What Ice failed to mention on that track, though, was that said burst probably would never have happened if not for an earlier record: "PSK, What Does It Mean?" by Philadelphia MC Schoolly D.

To Ice's credit, it's not like he hasn't acknowledged the influence in the intervening years. In an interview with Canada's Props Magazine (via Hip-Hop in America: A Regional Guide), Ice said, "The vocal delivery was the same... 'PSK is makin' that green,' 'Six in the mornin' police at my door.' When I heard that record I was like 'Oh, s***!' And call it a bite or what you will, but I dug that record." In a 2015 Billboard interview, Schoolly related how Ice called him up to get his blessing before releasing "6 'N The Mornin'," which Ice secured by playing his song over the phone and blowing Schoolly's mind.

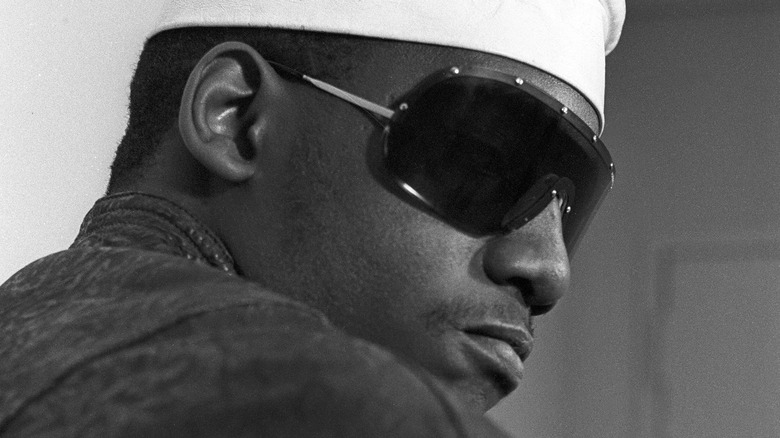

Rap's domination of pop music didn't start with Snoop Dogg, Dr. Dre, or Eminem

While hardcore rap artists were selling truckloads of records throughout the late '80s and early '90s, radio stubbornly refused to play pretty much anything but the soft stuff until 1993. Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg made a dent in the pop charts with "Nuthin' But a G Thang" from Dre's classic album "The Chronic" early that year, but its smooth, laid-back sound wasn't exactly hard on the ears of your average radio listener. In order for hardcore rap to start getting radio play, someone had to kick down the door — and it wasn't Dre or Snoop who did the kicking. That honor belonged to Onyx, an ultra-rugged four-man outfit from New York which assaulted the ears of listeners.

According to NPR, Rick Cummings, program director at L.A.'s Power 106, precipitated the shift when his station experienced a serious dip in ratings in the early '90s. Realizing that the hardcore rap crowd represented a vast untapped market, Cummings began experimenting with adding rap to the rotation. So well-received was the switch that Cummings soon completely retooled the station's format, and by 1993, other stations were taking notice. At precisely the right moment came "Slam," the lead single from Onyx's debut album "Bacdaf*cup" — a raucous, abrasive piece of hardcore rap helped along by a performance video bursting with so much energy that it could have been shot at a Slayer concert. "Slam" improbably peaked at #4 on the Billboard pop chart, instantly redefining what could be considered radio-friendly — and in a nice bit of serendipity, the song was co-produced by the legendary DJ Jam Master Jay of Run-D.M.C., the group that helped to prove rap's commercial viability in the first place.