TRAPPIST-1: The Galaxy's Tiniest Known Planetary System

In February 2017, NASA unveiled one of the most fascinating astronomical discoveries ever made. As always, the announcement of a NASA press conference filled social media with excitement, speculation, and the usual jokes about aliens. The reality, however, was even more outlandish than many of the rumors. The discovery was a planetary system that had been given the name of TRAPPIST-1. A tiny red dwarf star with an entourage of seven Earth-sized planets, like a miniature version of our own Solar System.

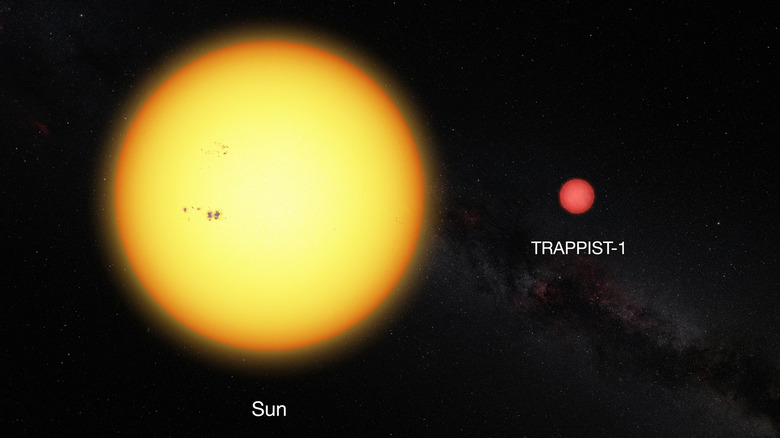

The name TRAPPIST-1 (named for the survey which discovered it) is actually the name of the star itself, and it truly is tiny. In size, as ESO shows, it's barely bigger than the planet Jupiter, here in our Solar System. It has far more mass than Jupiter but, compared to the blazing light of other stars, TRAPPIST-1 is barely an ember. Known as an ultra-cool red dwarf, stars like these are barely massive enough to shine at all, with only just enough mass to burn hydrogen in the process of nuclear fusion.

At a distance of roughly 12 parsecs (or 40 light-years), this little collection of worlds is right in our cosmic backyard. As NASA Exoplanet Exploration explains, it's such a fascinating little place that, within just a few years of its discovery, it had already become one of the most studied planetary systems in the galaxy. Like all the most interesting things in the night sky, the more it's studied, the more fascinating it becomes.

Under alien skies

From the surface of one of the worlds of TRAPPIST-1, other planets would be visible in the sky as clearly as the Moon is from the surface of Earth. The view from these worlds would truly look like something from science fiction. The reason, explained by NASA Exoplanet Exploration, is that the entire TRAPPIST-1 system is so tiny that it could fit within the orbit of Mercury.

Next to the Sun, Mercury is a scorching hot ball of iron and rock, slowly baking for 4 billion years, but a tiny star like TRAPPIST-1 only puts out a fraction of the Sun's heat. The result is that, even so close to their star, some of TRAPPIST-1's planets are found in the "habitable zone" – receiving just enough warmth from the dim starlight that liquid water can exist on their surfaces. Surface water means the skies of these worlds may even be full of clouds. Though, as New Atlas reports, some may not have such an appealing view, being likely wrapped in dense Venus-like atmospheres.

Orbiting such a dim star, the planets of TRAPPIST-1 are lit in eternal sunset, illuminated by what Space.com describes as "a salmon-colored light." As Science Reporter magazine explains, daytime on these worlds would never be any brighter than sunset here on Earth. A red dwarf like TRAPPIST-1 emits most of its light as infrared, invisible to human eyes.

Earth-sized worlds

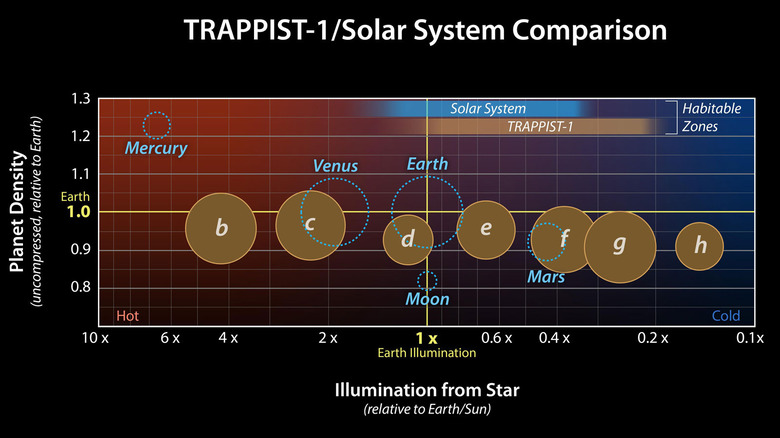

One of the most exciting things about the TRAPPIST-1 system is that all of its worlds are terrestrial planets: rocky worlds like Earth, with solid surfaces. For a long time, most of the exoplanets discovered in the galaxy were gas giants, like Jupiter and Saturn. As NASA explains, the first confirmed exoplanet discoveries were gas giants, mostly because they're easier to find, being so large and massive. TRAPPIST-1 is also remarkable for having a total of seven terrestrial planets. As NASA JPL notes, it's the largest group of Earth-sized planets ever discovered in a single star system.

A paper in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics examined the early data and found that, while two of the planets are largely made of rock, five of them likely have oceans, thick atmospheres, or blankets of ice. It's likely that these planets are less than 5% water. This may not sound like a lot, but it's a substantial amount. As a page from Michigan Tech mentions, only 0.02% of Earth's mass is water!

More recently, a study published in the Planetary Sciences Journal found that the TRAPPIST-1 planets are all quite similar to each other, and likely have a very similar composition to Earth in most ways but one: Earth is much denser. It could be that Earth contains more iron, or it could be that the TRAPPIST-1 planets contain more light elements, possibly in the form of layers of watery ocean.

An angry red sun

Red dwarfs can be unpredictable little things, occasionally throwing violent tantrums. Despite their small size, they can be prone to massive stellar flares, often earning the name of "flare stars," as a paper in The Astrophysical Journal discusses. These flares can emit a tremendous amount of X-rays and, as Space.com explains, this has led to many astronomers being doubtful that life could exist on the planets orbiting red dwarfs. The surfaces of these planets may be periodically blasted by radiation, meaning that life, if it can exist at all on worlds like these, may be confined to the oceans.

TRAPPIST-1 certainly seems to be no exception to this, showing frequent flares. A different study in The Astrophysical Journal even concluded that the planets in the TRAPPIST-1 system may be unsuitable for life, because of how these flares would continuously alter their atmospheres. But it isn't all doom and gloom. Renowned astronomer Phil Plait, in his blog at SyFy Wire, writes that even though the superflares that red dwarfs sometimes throw out may be up to 10,000 times as strong as anything the Sun can muster, they might not affect planets too severely. Planets tend to orbit around a star's equator, while the strongest flares are usually thrown out by the star's poles, meaning that any orbiting planets may not feel the brunt of a red dwarf's angry outbursts.

In the face of a star

All of TRAPPIST-1's planets are packed very close to their parent star. In their tight orbits, they lie deep within the magnetic field generated by convection currents within the star itself. So close, in fact, that an Astrophysical Journal study found that at least four of them are completely inside the star's corona.

Like with the Sun, a star's corona is essentially the star's extended upper atmosphere, stretching far out into space. It is a thin but extremely hot plasma, constantly streaming away into space in the form of a stellar wind. The same thing is constantly happening around the Sun and, as Space.com explains, the solar wind it emits gets caught in Earth's magnetic field, causing the vibrant aurorae which can often be seen near Earth's poles. Little is known about the corona of TRAPPIST-1, but it could be a potentially rather extreme environment for a planet. Constantly immersed in the stellar wind, any planet protected by a strong enough magnetic field may have brilliant aurorae illuminating its skies, as well as dim pink starlight.

Another slightly less comfortable possibility is that the star's magnetic fields could cause heating inside the planets themselves. A study in Nature Astronomy suggests that as a planet orbits inside TRAPPIST-1's magnetic field, it could undergo induction heating like a cooking pot on a hot stove. The result is that the innermost of these planets could be mostly molten, wracked by volcanoes, or even hiding subsurface oceans of magma.

Caught in a tidal grip

Being so close to their parent star also means that TRAPPIST-1's planets feel powerful tidal forces from the gravity of the star itself. The most extreme result of this, as a paper in Astrophysical Journal Letters describes, is that the planets could be tidally locked to the star, with one side constantly in daylight and the other trapped in a perpetual winter night.

Tidal locking, as Phys.org explains, is why the same side of the Moon constantly faces Earth, with the so-called dark side of the moon never visible from Earth's surface. A National Geographic documentary called "Extraterrestrial" explores how life might exist on such a world, confined to a habitable ring of the planet's surface, between the perpetual storms of the dayside and the deep-frozen night side.

It's not certain the planets will be locked, however. A study in Space Science Reviews suggests that they may simply rotate slowly, similar to Mercury in our Solar System. This same study also suggests that the tidal forces pulling on the planets may also be a major source of internal heating for the innermost TRAPPIST-1 planets, as the star's gravity causes them to flex while they orbit. As Space.com explains, this same tidal heating process is the reason why Jupiter's moon Io is the most volcanically active object in the Solar System.

Planets jostling for space

The planets of TRAPPIST-1 are in such tight orbits that their years last for only a matter of days. A NASA press release notes that even the outermost of these worlds has a year that lasts only 19 Earth days. It's a great place to live for anyone who enjoys New Year's celebrations. Science Reporter also makes the interesting observation that these planets are close enough together that they will feel each other's gravitational pull, tugging and jostling with each orbit. The result is that it's not easy to calculate the exact time each orbit takes. Depending on where the other planets are in the system, each year might be a slightly different length.

The planets are close enough together that a study in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society suggests their day lengths may even vary. This study explains that, while these planets are often assumed to be tidally locked, the way they interact with each other could make their rotation chaotic and unpredictable. These chaotic spin states mean that the day lengths of the TRAPPIST-1 planets may not be fixed. A day could remain the same length for thousands of years before suddenly changing, completely without warning!

Old worlds

There may be a lot about TRAPPIST-1's planets which is chaotic and unpredictable, but there's one thing that is quite certain. Their orbits are extremely tidy. A study published in the Planetary Sciences Journal found that all the planets of the TRAPPIST-1 system have very low eccentricities. In other words, they're almost perfectly circular and all in the same flat plane. This all means that the system is extremely stable. And, logically, it has to be this way. If the system was even slightly more disordered, it could throw everything catastrophically out of balance.

Everything suggests that this tiny planetary system has been there for a long, long time. TRAPPIST-1 is a very old star. According to a press release from UC San Diego, the star and its planets were born an estimated 7.6 billion years ago. This is substantially older than the Sun's age of 4.6 billion years (via Space.com). Before the Sun even began to form, these planets were already billions of years old, bathing in pink starlight.

Strange homeworlds

Whether or not TRAPPIST-1's planets may be able to host life is an ongoing debate among astronomers and astrobiologists. There are all kinds of pros and cons to weigh. Some studies have constructed detailed climate models to try and assess the habitability of the system. One study, in particular, published in Astrophysical Journal Letters shortly after TRAPPIST-1's discovery, found that it's likely that the inner three planets may have undergone a runaway greenhouse effect, leaving them hot and dry like Venus, while the outer three might be snowball planets wrapped in permafrost. The middle planet, however, could possibly have water oceans.

Another study published in The Astrophysical Journal seems rather more optimistic, noting that three, possibly four, of the TRAPPIST-1 planets receive the right amount of starlight to have liquid water on their surfaces. If this study is correct, it increases the chances that at least one of these planets could potentially be habitable. Still more studies have suggested that the worlds of TRAPPIST-1 could be brimming with liquid water. One report, described by Space.com, suggests that some of them could contain over 250 times as much liquid water as all of Earth's oceans combined, giving plenty of swimming space for prospective alien leviathans.

Life in red sunlight?

In astrobiology, the most promising targets in the search for extraterrestrial life are Earth-sized planets with liquid water on their surfaces, as noted by a paper published in Physics-Uspekhi. Earth is, so far, the only place in the universe known to harbor life, and Earth life cannot exist without water. This is why, as National Geographic explains, astrobiologists look for water in hopes of finding extraterrestrial life. It's important to look for what's proven to exist before considering other possibilities.

Based on climate models, as an Astrophysical Journal Letters study suggests, at least one of the TRAPPIST-1 planets may have liquid water, suggesting that at least one of these worlds may possibly be home to some kind of life. But the word "possibly" is carrying a lot of weight in that statement. Other astrobiologists, however, have pointed out that surface water isn't everything. Jupiter's moon Europa has oceans below a thick surface layer of ice and, as Universe Today discusses, some astrobiologists have even considered the possibility that life may not require water at all. This suggests that even the cold outer planets of TRAPPIST-1 may still be places where, as the saying goes, life could find a way.

The TRAPPIST project

TRAPPIST-1 may seem like an odd name for a star. The name comes from the TRAPPIST project which first discovered it. Standing for TRAnsiting Planets and PlanetesImals Small Telescope, the project runs a pair of robotic telescopes based at ESO's La Silla Observatory in the Atacama desert of Chile, and at the Oukaïmeden Observatory in Morocco's Atlas Mountains. The TRAPPIST project is an ongoing dedicated planet-hunting survey, and one of its main aims is to discover and characterize exoplanets. The project originated in Belgium, led by the University of Liège, and, yes, the name is inspired by the world-famous Belgian Trappist beers.

TRAPPIST is just one of the 21st century's numerous planet-hunting missions which have been dutifully surveying the skies. As of April 2022, the NASA Exoplanet Archive has recorded over 5,000 confirmed planets in orbit around other stars, with thousands of other sightings still waiting for official confirmation (it takes a lot of time and patience to be an exoplanet astronomer). The discovery of TRAPPIST-1 had an important role to play, however. It inspired many planet hunters to look more seriously for worlds orbiting red dwarfs. As a conference paper at the 14th Europlanet Science Congress notes, another ultra-cool red dwarf, known as Teegarden's Star, has since been found to possibly have a couple of planets too.

Billions of tiny ruby suns

A lot of astrobiology studies, as Astrobiology at NASA explains, look for yellow stars like the Sun. It's a captivating idea, that somewhere there may be another star much like ours, and a planet that could potentially be a second Earth. But some astrobiologists have considered that red dwarfs like TRAPPIST-1 may actually be better places to look.

What red dwarfs lack in size, they more than make up for in numbers. According to ESO, around 80% of the stars in the galaxy are red dwarfs, and it's estimated that they're carrying tens of billions of planets in tow. Another point in the favour of red dwarfs is that they're incredibly long-lived. As Britannica mentions, red dwarfs can keep shining for trillions of years. In other words, no red dwarf has ever died in our universe, because the universe itself isn't old enough yet.

Of course, not everyone agrees on whether it's even possible for life to exist in orbit around a red dwarf star. A paper in the Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics, for example, concluded that red dwarf planets aren't likely to host life. But then, statistically speaking, maybe it doesn't need to be likely. Maybe it only needs to be possible. Buying enough lottery tickets makes it possible to win any lottery – and with the overwhelming number and lifespan of red dwarfs in the galaxy, this is one lottery the universe might eventually win.