The Tragic Story Of The 16th Street Baptist Church Bombing

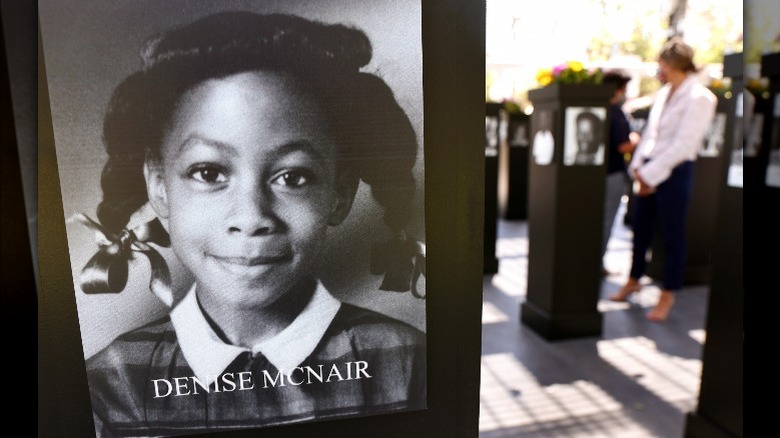

On September 15, 1963, a bomb exploded at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, killing four girls and injuring numerous bystanders. The girls were Addie Mae Collins, 14; Cynthia Wesley, 14; Carol Robertson, 16; and Denise McNair, 11 (per the Birmingham News). The bombing rocked the nation, and the country exploded in anger over the callous murder of four young girls who were attending church. President John F. Kennedy released a statement condemning the violence and immediately promised the services of the FBI. Even the famous segregationist Governor of Alabama, George Wallace, expressed sympathy and vowed to catch the criminals responsible for the explosion, and U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy's top two aides flew into Birmingham that night to start investigating.

The FBI was slow to make any arrests, but by 1965 they had narrowed down their suspects to a select few they were sure were responsible (per the FBI). Eventually, three white men, Robert Chambliss, Thomas Blanton, and Robert Frank Cherry, were convicted of plotting and executing the bombing. They all received life sentences in prison.

America has come a long way in fighting racism over the last 60 years, but nothing can ever heal the wounds that opened that fateful day in late 1963. This is the tragic story of the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing.

The city was a hotbed of racism and bigotry before the bombing

In the 1960s, Birmingham, Alabama, was one of the biggest epicenters of racism in the United States. The city was divided racially and highly segregated (per the National Parks Conservation Association). The city was also incredibly violent, and the police routinely beat Black Americans and civil rights protestors whenever they marched. According to an article in the Birmingham Post-Herald, there had been at least 20 bombings in the city since 1955, and most of them were directed at either churches or Black families moving into the so-called "white section" of town, sarcastically known as "Dynamite Hill" because of the constant explosive attacks. The white supremacists had targeted several Black reverends and bombed at least six churches — some of them more than once.

In January of 1963, Alabama elected notorious segregationist George Wallace to the governorship, who ran on the campaign slogan, "Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever!" (via History). Between his inauguration and the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, at least four other bombs had exploded in the city, including two at the home of prominent Black civil rights attorney Arthur Shores, one of which occurred just two weeks before the bombing at the 16th Street Church. The Church itself was the site of many civil rights protests, including several from the Birmingham Campaign, and that likely made it a target for the bombers (per the National Parks Service).

The anonymous phone call

Just minutes before the bombing, a young Black church-goer, Carolyn Maull McKinstry, was standing in the girls bathroom. It was just before the 11:00 a.m. morning youth service was set to begin, and McKinstry was with four of her friends, Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, Carol Robertson, and Denise McNair, "primping in front of the restroom's large lounge mirror" (per McKinstry's autobiography "While the World Watched"). Collins' sister Sarah was in the bathroom too, but McKinstry could not see her. McKinstry was "best friends" with Wesley, McNair, and Robertson, and she called Addie Mae "a sweet, quiet girl."

Just before 10:30 a.m., McKinstry left the bathroom and headed upstairs to prepare the reports and summary for the upcoming service. As she made her way up the stairs and out of the basement, she heard a phone ringing in the church office. When she answered the phone, before she could even greet the other caller, a cold, male voice said the words "three minutes" before hanging up. Soon after, the bomb exploded under the stairs.

McKinstry had narrowly avoided becoming another casualty by mere seconds, as the explosion went off just after the phone call. The anonymous caller has never been identified since. In an eerily similar incident, Robert Chambliss, who was eventually convicted of the bombing, reportedly told his niece a few days prior, "Just wait until Sunday morning and they'll beg us to let them segregate" (via the National Parks Service).

The conspirators used a lot of explosives

In order to make sure the explosion would be as devastating as possible, the bombers used a lot of dynamite. According to History, they used at least 10 to 15 sticks of the powerful explosive, all of them hidden underneath the stairs at the back of the church. The blast was so devastating that, in addition to knocking out most of the bathroom wall near the stairs, it created a massive crater in the basement. Shrapnel and debris from the exploding building blanketed the area, and a passing motorist was thrown out of his car. The windows of the surrounding buildings were shattered, and any cars parked near the church were completely destroyed. In "Crimes and Trials of the Century," Steve Chermak explains that even people 30 blocks away could hear the explosion and that nearly all of the stained glass windows in the church, except one dramatic piece, were shattered.

After the explosion, people started to stumble out of the church, dazed, and a few of them likely concussed. Immediately, bystanders and civil defense workers started to search the debris for any sign of life, and some of the victims were so covered in glass and blood that they were unrecognizable. According to the Birmingham Post-Herald, none of the previous bombings in Alabama since 1955 had resulted in any deaths, but the 16th Street Baptist Church became the one tragic exception.

The explosion severely disfigured the four dead girls' bodies

All of the girls killed in the explosion were between the ages of 11 and 16, and they were all standing in the basement, near the stairwell where the explosives had been placed. According to Frank Sikora in "Until Justice Rolls Down: The Birmingham Church Bombing Case," the explosion sounded like "a loud crack of thunder, almost ear-splitting." Most of the people in the church that day were left with only minimal scrapes and bruises, but rescuers quickly realized that underneath the rubble, in the basement, there were probably more victims. Bystanders and aid workers carefully extracted each of the four girls from the debris. One helper reported hearing noises from one of the girls as they pulled her out, indicating she had survived the blast but was succumbing to internal injuries. Another girl was buried in the rubble and injured, but she was alive.

All of the children were mutilated and maimed from the explosion. Cynthia Wesley's body was so disfigured that her parents had to identify her based on her clothing and a ring she was wearing. Denise McNair had a skull fracture 2.5 by 1.5 inches and several lacerations on her shoulders and face. McNair's parents gave an interview to NPR in 2008, where they described seeing her with a piece of mortar "mashed in her head."

One of the dead girls' sisters was left permanently blind

There were five girls in the basement bathroom of the 16th Street Church, on the morning of September 15, 1963. Four of them, Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, Carol Robertson, and Denise McNair, were killed in the explosion. The fifth, Sarah Collins (pictured above), Addie Mae's sister, miraculously survived the blast and was pulled out of the rubble alive (per Frank Sikora in "Until Justice Rolls Down"). Sarah remained conscious the entire time and was screaming for her sister, who she thought had escaped the bathroom alive.

When she was finally rescued, paramedics found 21 pieces of glass embedded in her face, which eventually led to her getting a glass eye, and they found many more shards stuck in the rest of her body. She had a deep cut on her right leg and was rushed to the University Hospital immediately. It took her family days to let Sarah know about the fate of the other girls in the bathroom, including her sister Addie Mae. She first found out about their deaths after overhearing it on the radio from her hospital bed (via The Owosso Argus-Press). Collins remained in the hospital for weeks, with her face and eyes covered in bandages most of the time.

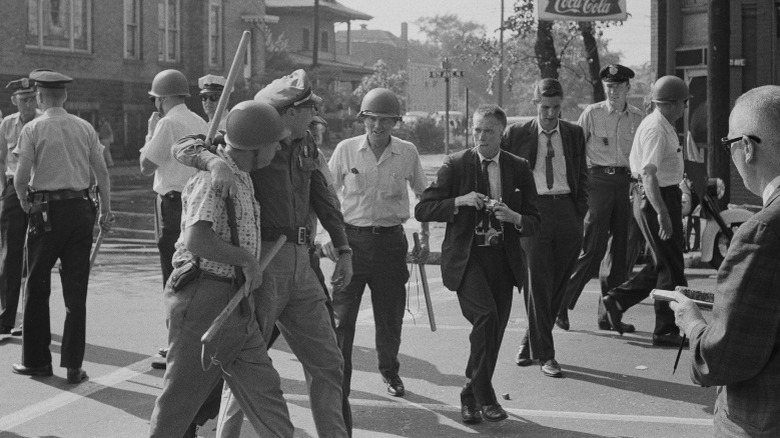

The bombing sparked a wave of racial violence throughout the city

The bombing at the 16th Street Baptist Church ignited an explosion of racial violence throughout the city. According to The Washington Post, several Black-owned businesses were set on fire with gasoline, but luckily they were extinguished before anyone was injured. Reinforced police units were immediately sent to patrol the city, and the National Guard stood dressed for battle, ready to be deployed. Police urged residents, both Black and white, to keep their children inside as random shootings and assaults plagued the city. A group of roughly 2,000 Black community members converged on the church and protested for hours while the white police force fired their rifles in the air and struggled to subdue them.

According to Sara Bullard in "Free At Last: A History of the Civil Rights Movement and Those Who Died in the Struggle," police shot and killed Black teenager Johnny Robinson, who had been part of a group of kids throwing rocks at police. Also, two white teenagers, riding around on a motor scooter emblazoned with confederate stickers, shot and killed a 13-year-old kid named Virgil Ware, who was riding on his brother's bicycle handles. The killer, 16-year-old Larry Joe Sims, was convicted of second-degree manslaughter, not murder, and sentenced to only seven months in jail. He was released by the judge in less than a week.

White supremacists celebrated the attack

While Black families mourned and their community was shaken, callous white supremacists celebrated the bombing and rejoiced. Just a few days after the bombing, Connie Lynch, a vocal white supremacist, made a horrifying speech to a group of KKK followers, praising the bombers (per Wyn Craig Wade in "The Fiery Cross: The Ku Klux Klan in America"). Lynch stated they deserved to be rewarded with medals commemorating their deed and spewed racist garbage about the four victims. He claimed the four girls, Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, Carol Robertson, and Denise McNair, "weren't children" and expressed twisted gratitude for the tragedy.

However, there were also some prominent white voices that condemned the attack. President Kennedy released a statement pledging to bring the perpetrators to justice and expressed "a deep sense of outrage and grief." Just one day after the blast, white lawyer Charles Morgan made a speech at the Birmingham Young Men's Business Club, where he blasted the white community for contributing to the festering racism by their refusal to stand against it (via The Atlantic). "Who did it? Every last one of us is condemned for that crime and the bombing before it and a decade ago. We all did it," he remarked.

The funerals for the slain girls were held separately

The funerals for the victims were held within a week of the bombing, and members of the community flocked to attend and pay their respects. Dr. Martin Luther King was in town to work with civil rights leaders in the aftermath of the bombing and helped plan the funerals. However, Carole Robertson's parents chose to have their daughter's funeral separate from the other three girls for reasons that are somewhat unclear. In "Until Justice Rolls Down," Frank Sikora quotes Robertson's mother Alpha when saying, "We didn't know at first about that [the other funeral], and we had just made our own plans for Carole." Alternatively, in "Carry Me Home: Birmingham, Alabama, and the Climactic Battle of the Civil Rights Revolution," Diane McWhorter suggests that the Robertsons deliberately held a separate funeral for Carole because they wanted to remember her as an individual.

Robertson's funeral was held first at a local church on September 17, and an estimated 4,500 people attended (per the Baltimore Afro-American). The following day, the joint funeral for Denise McNair, Addie Mae Collins, and Cynthia Wesley was held at another church, with Dr. King presiding. Dr. King gave a powerful eulogy and spoke to the crowd about the tragedy and its impact on the civil rights movement (via the Ocala Star-Banner).

Did J. Edgar Hoover try to prevent the prosecution of the bombers?

Due to the slow nature of investigations into the Baptist Street Church bombing and the lack of criminal charges brought in the 1960s, many people have suspected that former FBI director J. Edgar Hoover (above middle) purposefully withheld evidence and blocked the prosecution of the conspirators. However, no concrete evidence has ever emerged proving Hoover deliberately did anything illegal. On their website dedicated to the bombing, the FBI insists that Hoover never tried to withhold evidence or block any prosecutions, but rather he was concerned with preventing leaks and did not think he had enough evidence to get a conviction.

Regardless, evidence has also shown that Hoover repeatedly refused to work with local police. In ""Until Justice Rolls Down," Frank Sikora notes that Alabama Attorney General William Baxley battled with Hoover for over five years trying to get access to the FBI case files. In "The Fiery Cross: The Ku Klux Klan in America," Wyn Craig Wade argues that three eyewitnesses identified Robert Chambliss, and several other Klansmen, at the site of the bombing hours before the explosion, but Hoover brushed them off. Five months later, Hoover again blocked FBI agents in Birmingham from presenting evidence to the U.S. Atty. Gen. Robert Kennedy (above right), reportedly because he was worried about it energizing the civil rights movement. In 1980, it emerged that Hoover purposefully stopped testimony from being given to civil rights prosecutors (via The Washington Post).

One of the murderers was initially only fined and given a suspended sentence

In the immediate aftermath of the bombing, local authorities tried in vain to get information about the perpetrators. The city had been the site of constant bombings for the past decade, and in the month prior, Birmingham Mayor Albert Boutwell and the Birmingham City Council started a fund that was intended to entice potential witnesses to come forward (via Frank Sikora in "Until Justice Rolls Down"). After the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, people from throughout the country started to donate to the fund in hopes of securing information and, eventually, convictions. Within days the fund had reached $76,000, up from the initial goal of $50,000, but there was still no significant information by the end of the following year.

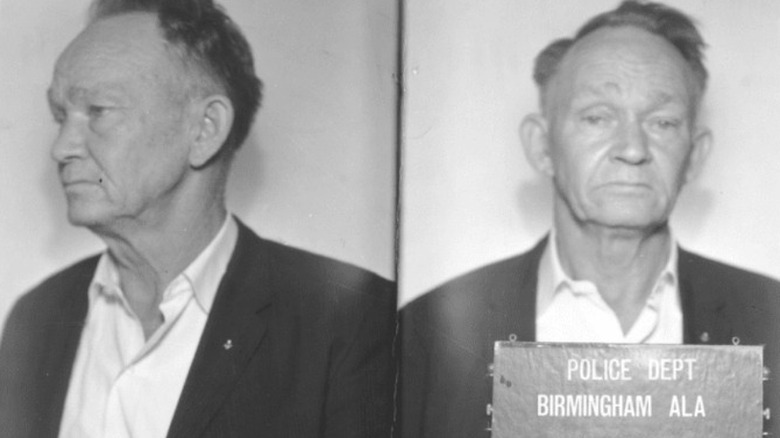

Meanwhile, the FBI had immediately started to pursue and investigate Ku Klux Klan members in the area. On September 30, two weeks after the bombing, the Alabama Department of Public Safety announced the arrest of three men, including Robert Chambliss (pictured above), who was eventually sentenced to life in prison in 1977 for his role in the bombing. Initially, however, they were not charged with murder, or even as conspirators in a plot to bomb the church; instead, they were charged with a misdemeanor, possession of dynamite. They were fined $1,000 and given suspended sentences of six months each. Robert Chambliss would remain free until his arrest and trial in 1977, over a decade later.

The first murder trial did not take place until 1977

In 1970, Alabama elected 28-year-old William Baxley (pictured above) to be the state's new Attorney General. Baxley was attending law school at the University of Alabama in 1963 at the time of the bombing, and he became obsessed with securing a conviction. When he took office in 1971, the 16th Street Baptist Church case was one of the first he reopened (via The Day). Baxley zeroed in on Robert Chambliss, one of the men long suspected of being involved in the bombing and one of the four listed as possible suspects on the FBI's 1965 list. Chambliss was indicted on first-degree murder charges in 1977, convicted that November, and given a life sentence. Baxley's powerful closing argument was a key point in the trial, bringing several members of the jury to tears with his fiery passion.

During the trial, one of the witnesses, Elizabeth Cobb, testified to the severe racism that had infected Chambliss (via "Until Justice Rolls Down"). She stated that Chambliss routinely used racial epithets when speaking about Black people and that he joined the KKK "in order to fight to maintain segregation." She also shockingly stated that Chambliss had told her the bomb "wasn't meant to hurt anybody. It didn't go off when it was supposed to." Chambliss died in prison in 1985, at age 81, from a heart attack (per the LA Times).

Two of the bombers were not sentenced to life in prison until nearly four decades later

While Robert Chambliss was convicted of first-degree murder in 1977 and sentenced to life in prison, he was the only suspect prosecuted for the case in the 20th century. It was not until 2001 to 2002 that two of the other bombers, Thomas Blanton and Bobby Frank Cherry, were convicted and sentenced to life behind bars (per the American Bar Foundation).

In 1993, the agent in charge of Birmingham's FBI office, Rob Langford, had reopened the case after meetings with several civil rights leaders. The new prosecutions were predicated on newfound evidence, including recently discovered surveillance tapes from the 1960s and the willingness of former friends and acquaintances to finally testify publicly. Blanton's trial lasted only a week, and it took the jury all of two-and-a-half hours to convict him on all four counts of first-degree murder. Cherry tried to get his trial thrown out, arguing he was not competent to stand trial due to his advanced age and diagnosis of dementia. However, this effort failed, and Cherry, too, was eventually convicted of first-degree murder. Both defendants were given life sentences.

Cherry died of cancer in 2004 while in prison at the Kilby Correctional Facility near Montgomery, Alabama (per The New York Times). Blanton died in 2020 while incarcerated at Donaldson prison near Birmingham (via Associated Press).

One likely conspirator was never charged

Though Robert Chambliss, Thomas Blanton, and Bobby Frank Cherry were all eventually convicted of first-degree murder, and sentenced to life in prison for their roles in the bombing, one longtime suspect, unfortunately, evaded prosecution. From the beginning, the FBI suspected Birmingham KKK member Herman Frank Cash (and his brother Jack Cash) as another of the bombers (per "Until Justice Rolls Down"). According to T.K. Thorne in "Last Chance for Justice: How Relentless Investigators Uncovered New Evidence Convicting the Birmingham Church Bombers," witnesses had identified Cash, along with Blanton and Chambliss, in front of the church on the morning of the bombing. Cash and Cherry had reportedly been the ones to place the bomb on the steps of the church.

By May of 1965, the FBI had narrowed down the list of suspects from hundreds to just five, which included Cherry, Blanton, Chambliss, and Cash, along with Troy Ingram, who was "probably" involved. However, none of them were arrested on murder charges at the time, as the FBI deemed there to be insufficient evidence for a conviction. According to the FBI, Cash died in 1994, before any charges were ever brought against him.

Was an FBI informant involved in the bombing?

While the FBI only acknowledges four official suspects in the case, Robert Chambliss, Thomas Blanton, Herman Frank Cash, and Bobby Frank Cherry, some people think that there is a possible fifth suspect who is not on that list.

In the early 1960s, the racial violence in Birmingham, Alabama, was so intense that the FBI had placed an undercover informant in the KKK, Gary Thomas Rowe (pictured above testifying, with his face covered to obscure his identity). According to Diane McWhorter in "Carry Me Home," Rowe was an eighth-grade dropout from Savannah, Georgia, who had previously been fined for impersonating a police officer in 1956. However, he was accepted as an FBI informant and used to infiltrate the KKK because of his alleged connections.

Rowe's history with the agency is incredibly controversial. Per the Ocala Star-Banner, Rowe was suspected by many to have been involved in not monitoring the KKK but in helping them plan multiple bombings. He admitted to killing a Black man during a riot at around the same time, and he failed multiple polygraph tests about his role in the bombings. Captain Jack LeGrand of the Birmingham Police Department was one of the original investigators on the case, and he was convinced that Rowe was involved in the bombings (per Frank Sikora in "Until Justice Rolls Down"). Rowe died of a heart attack in 1998, after living most of his life in witness protection (per The New York Times).

If you or a loved one has experienced a hate crime, contact the VictimConnect Hotline by phone at 1-855-4-VICTIM or by chat for more information or assistance in locating services to help. If you or a loved one are in immediate danger, call 911.