The Untold Truth Of Britain's WWI Internment Camps

World War I ushered in many firsts, from widespread use of poison gas to trench warfare (via Imperial War Museums). As the earliest war waged on land, air, and sea, it also brought with it the newfangled threat of aviation attacks on British civilians, with nearly 4,800 wounded or killed during German air raids.

The so-called "War to End All Wars" saw Great Britain's first mandated military service with the passing of the 1916 Military Service Bill. And it's easy to see why men felt apprehensive about serving, especially after the initial excitement wore off. World War I marked the introduction of gas masks, flamethrowers, submarines, and tanks into mainstream battle — even as cannons, sabers, and horses persisted. The rules of warfare changed in real-time with devastating consequences for all involved. And the emergence of new technologies and weapons revamped the rules of how humans killed each other, turning the entire globe into potential theaters of war and civilians as targets.

The Great War also meant the worldwide imprisonment of those termed "enemy aliens," according to the International Encyclopedia of the First World War. For example, more than 400,000 immigrants lived in European prison camps for years on end. And roughly 32,000 Austro-Hungarians and Germans faced incarceration in the British Isles between 1914 and 1919. Ethnicity-based incarceration underscored the xenophobia running rampant because of the bloody conflict. Here's what you need to know about the untold truth of Britain's WWI internment camps and their aftermath.

Great Britain led the charge for mass internment of civilians

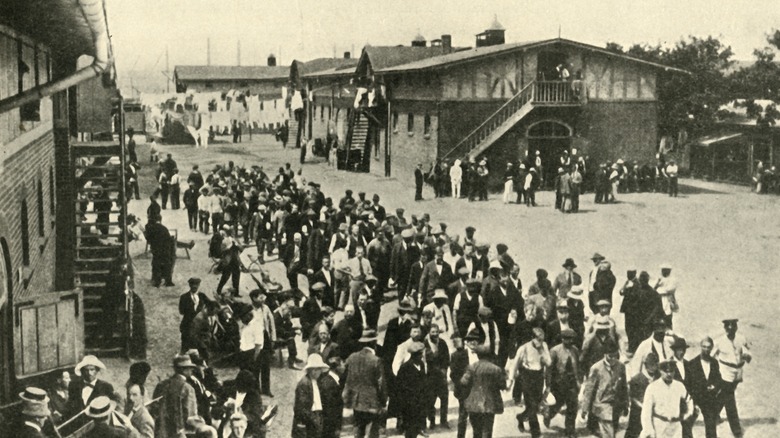

As early as 1914, Great Britain led the charge to incarcerate foreign-born civilians, according to The Conversation. Yet, despite Great Britain's pioneering of internment camps, a dearth of academic information on the subject exists (per Reviews in History). Nevertheless, Britain's treatment of enemy aliens marked one of the first attempts at mass imprisonment of non-combatants in the 20th century, as reported by Jacobin.

German immigrants, in particular, had flocked to Great Britain starting in the 19th and early 20th centuries (via Our Migration Story). They left Germany for various reasons, including the chance to escape prevalent intolerance in their homeland. Some hoped to avoid the competition for resources resulting from a German population boom. To streamline their immigration experience, individuals established networks in the British Isles to support one another. As an increasing number of Germans made Great Britain their home, they paved the way for fellow ex-pats.

Although new arrivals dispersed throughout the nation, a large concentration settled in London. By 1911, they numbered more than 53,000, with about 50 percent living in the East and West End of London. With the onset of World War I, control of these immigrant populations became the name of the game, and that's where concentration camps came into play. Over the course of the war, many Austrians, Germans, Turks, and Bulgarians living, working, or visiting the British Isles faced incarceration. Enemy aliens in other nations dealt with similar situations.

The British Isles focused on male immigrants

Although the British Isles pioneered interning enemy aliens, the practice soon became a worldwide phenomenon, as reported by the International Encyclopedia of the First World War. Soon, every corner of the world housed a camp where immigrants from enemy nations moldered away waiting for an end to the conflict.

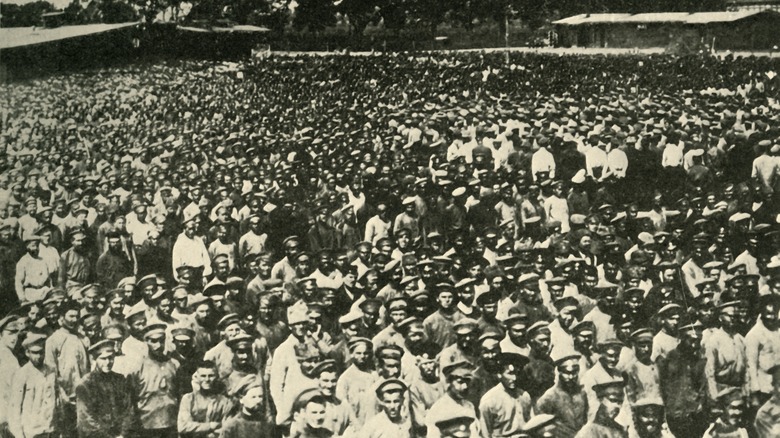

While targeted demographics might vary slightly, the British went after males between the age of 17 and 55 years old (via Our Migration Story). Even neutral nations, such as the Netherlands, got in on the imprisonment fury. Roughly 800,000 European civilians spent time in internment camps during or after the Great War.

In Great Britain, tens of thousands of immigrant men were relocated to the Isle of Man or near the Scottish Borders. Other parts of the Commonwealth followed the example set by the mainland. (More on this later.) Yet, despite the predominance of these camps, it seems that the stories of internees have largely been lost to British history, according to The Conversation. While faint memories about the internment camps exist in some communities within the UK, the phenomenon barely receives a footnote in many books about the Great War.

Media propaganda bolstered public opinion

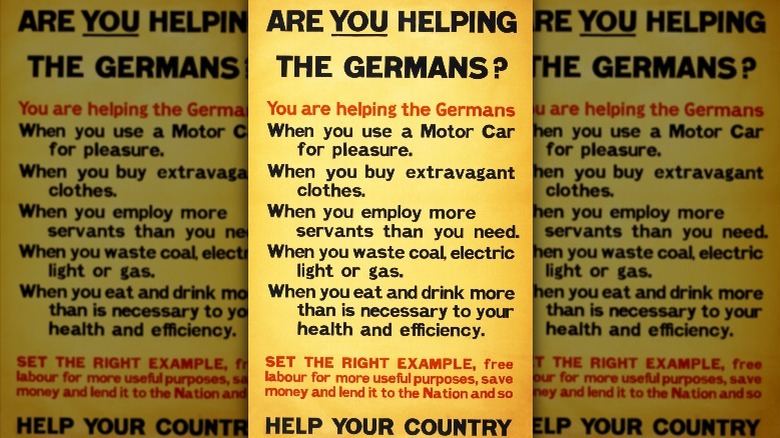

To support the British government's push to imprison those deemed potential threats to national security, the media got busy (via The Conversation). They whipped up stories strategically designed to fuel hatred and fear of immigrants from enemy nations.

Headlines spewed vitriol about potential threats from alien residents and travelers. Journalists relied on demonizing wording such as the "German octopus" and the "lowest type of Hun" to describe Germans and German Jews. According to the British Library, newspapers and magazines used hefty doses of atrocity propaganda to paint enemy combatants as war criminals. This wasn't a difficult task since the Great War marked history's first widespread application of total war. Over the course of the conflict, civilians died in the millions, per the British Library. And it's no coincidence that the first genocide happened during World War I, too, the widespread extermination of Armenians living in the Ottoman Empire (via History).

These journalists employed emotion-laden rhetoric to justify their nation's actions, stir up fear of the enemy, fortify the support of allied nations, and ensure the cooperation of neutral nations. Sensational stories also fomented the desire to place alleged enemy aliens in government custody.

Waves of incarceration coincided with violence

As soon as WWI began, the British government limited German immigrant movement with the Aliens Restriction Act (via Our Migration Story). This act forced immigrants to register with local law enforcement, and it kept them within a five-mile radius. What's more, it prohibited all German clubs and newspapers. But the pain felt by immigrants in the British Isles didn't end there. The government enacted measures allowing for the confiscation of immigrant property without compensation and the closure of all German-owned businesses. These rules made life impossible for those deemed enemy aliens and their families.

The targeting of immigrants culminated with the incarceration of non-residents and foreign-born immigrants in the British Isles. But imprisonment didn't prove consistent, especially at the beginning of the war. Rather, it waxed and waned with instances of xenophobia and violence against those deemed foreign, according to the International Encyclopedia of the First World War. October 1914 and May 1915 marked especially violent episodes against immigrants and visitors in towns and cities across the nation.

Due to the violence, those targeted were sometimes imprisoned for their own safety. Nevertheless, the British government gave a one-dimensional justification for the imprisonment of immigrants, arguing it was an effort to satisfy the "strong feeling against Germans roused by the atrocities ... in Belgium." Incarceration based on the barometer of public opinion meant immigrants led uncertain existences that changed rapidly based on capricious public opinion — and all of this was fermented by media propaganda.

The first prisoners were quietly released

Prisoners taken between November 1914 and February 1915 faced a different fate than those brought in later, according to the International Encyclopedia of the First World War. Most got released without fanfare during periods when xenophobia waned, and their public safety no longer appeared threatened. Unfortunately, waves of public violence proved hard to predict and could get nasty. This sometimes included the looting and damage of immigrant-owned establishments.

As the media continued to foment Germanophobia and xenophobia in general, immigrants suffered. Newspapers portrayed members of the Central Powers as financial rivals and insufferable brutes. As a consequence, people from those national origins had figurative targets painted on their backs. In other words, prisoners released by the government navigated dangerous waters that changed daily based on the latest news from the Front.

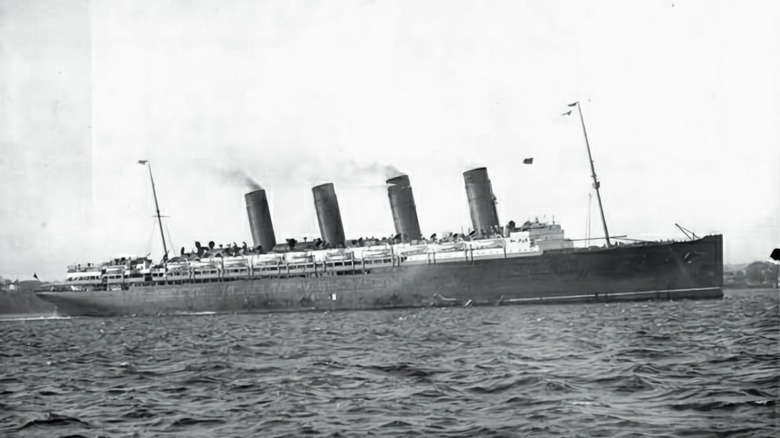

What didn't change was the general suspicion that enemy aliens represented dangerous outsiders who might act as spies. The same went for their demonization in the press and among members of the public. No wonder the British government acted quietly when liberating these immigrants. Officials understood just how tenuous the position was for Germans, Bulgarians, Austro-Hungarians, and Turks in World War I Great Britain. But then everything changed forever with a catalyst that brought America into the war and made Germany look very, very bad in the world's eyes: the sinking of the Lusitania.

The sinking of the Lusitania ramped up imprisonment

The pattern of incarceration and release in Great Britain stopped on May 7, 1915, with the destruction of the Lusitania (via History). The luxury steamer sank in 15 minutes after a German U-boat shot two torpedoes into it. All told, 1,195 civilians perished in the tragedy, including 128 American citizens. To say that the sinking strained German and American relations to the breaking point is an understatement. In the aftermath, the United States entered the war on the side of the British and French.

But Americans weren't the only people enraged by the event. Brits took to the streets during the "Lusitania riots," according to the International Encyclopedia of the First World War. Across the nation, violence broke out against Germans, causing a serious public threat, per the National Archives. The Lusitania also marked a turning point when it came to the mass incarceration of male enemy aliens by the British. It marked the death knell of quiet releases.

As a result of this change in policy, prisoner numbers swelled from 12,871 in May 1915 to 32,400 by November of that year. To oversee these incarcerations, officials created the Aliens Advisory Committee for England and Wales, and Scotland had a separate committee. Despite the design of these committees, there was little transparency in their decisions and actions. Meetings occurred behind closed doors, and the records they kept didn't make it to the present.

Daily life for internees

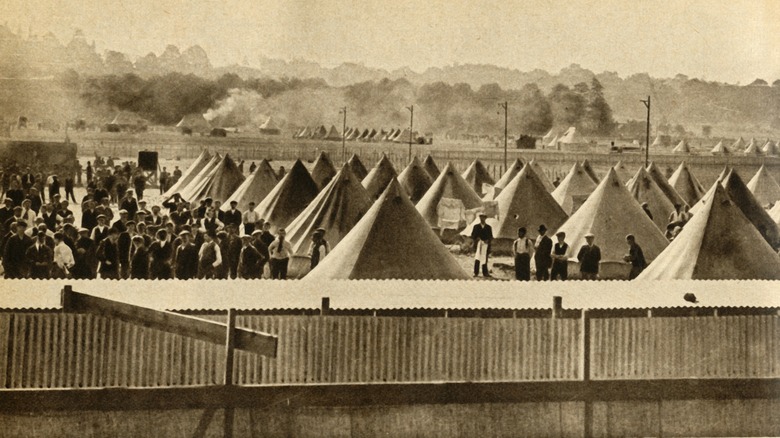

Many of those incarcerated as blowback for WWI faced indefinite relocation away from the British mainland, according to The Conversation. Tens of thousands were transported to the Isle of Man where they took up forced residence at Knockaloe Camp. They lived in huts built for 60 men apiece like military barracks (via Richard Dove's "Totally Un-English?: Britain's Internment of 'Enemy Aliens' in Two World Wars"), and visitors can still see the concrete platforms where these open-plan wooden structures stood.

Although the British Isles housed at least 16 internment camps, Knockaloe Camp represented the largest. It contained approximately 20,000 inmates locked up for years behind barbed wire fences. Knockaloe boasted its own post office and railway line, and it included four camps divided into 23 compounds. Boredom proved chronic, but the most inventive internees stayed busy by continuing their occupations or providing services to those within the camp. As a result, the camp contained active shoemakers, hairdressers, and tailors. Prisoners took classes, and clubs and organizations sprang up catering to drama, sports, and music.

Despite the industrious nature of the prisoners, boredom, uncertainty, and depression haunted them. Dr. Vischer, a Swiss camp inspector, referred to this admixture of ennui and emotion as "barbed-wire disease." This so-called disease not only dogged inmates during their incarceration but followed them for the rests of their lives in the form of permanent psychological scarring.

Prisoner treatment reflected national image concerns

Despite the decision to mass incarcerate enemy aliens, Great Britain also wished to maintain a favorable public image, according to the International Encyclopedia of the First World War. It was a tough line to walk. Especially when imprisoning innocent people for an undisclosed amount of time based solely on their country of origin. To make the situation as humane and PR-friendly as possible, prisoners enjoyed relatively decent treatment within the camps.

What's more, the nation made it clear that factors such as class distinction would be respected in the camps. This meant constructing "gentlemen's camps" reserved for members of the upper crust. Privileged facilities existed at Lofthouse Park near Wakefield and on the Isle of Man at Douglas. One internee of Lofthouse Park described it as a "true Beamtenstaat" or "bureaucratic state" where everyone took pleasure in exercising an official position.

The British judiciously and meticulously followed international law to ensure the preservation of their national image as highly civilized. After all, British media wished to continue labeling the Germans as barbaric, which meant they needed to provide an exemplary contrast. In essence, the wealthiest members of camp society enjoyed an extended, involuntary vacation behind the barbed wires of their camps. But even the most impoverished internees received the humane treatment guaranteed by international law.

How international law shaped the internment experience

Great Britain waged both physical and reputational warfare against Germany and its allies (via the International Encyclopedia of the First World War). This involved allegations that Germany had acted barbarically in Belgium and violated international law. To play the most effective foil to its Teutonic counterpart, Great Britain positioned itself as a highly civilized nation that wouldn't give in to cruelty and vindictiveness even in the face of brutal, total war.

There were many ways the nation managed a positive image despite incarcerating tens of thousands. Great Britain adhered strictly to international law obligations as set forth at the Hague Convention of 1899, according to Richard Dove's "Totally Un-English?: Britain's Internment of 'Enemy Aliens' in Two World Wars." Internees never faced forced labor, and women and children remained free throughout the war (although their movements were limited and monitored). Inspections from neutral embassy officials, including the Swiss and the Americans, ensured nothing cruel or unusual happened behind closed doors.

During a 1914 visit from the American embassy, officials noted, "Their quarters are comfortably furnished but without luxury" (via "Totally Un-English?"). While intentional physical harm proved unlikely in internment camps, the devastating psychological experience of being imprisoned for years with no end in sight persisted. Yes, accommodations felt comfortable and food rations fair. But internees faced years without seeing family members, unwarranted scrutiny, and alienation from British society at large.

The British used enemy aliens as bargaining chips

By March 1917, Great Britain held 10 times as many German civilian prisoners (36,000) and 50 times as many Austro-Hungarians (11,000) as British citizens incarcerated in Germany and Austria-Hungary, per the International Encyclopedia of the First World War. The vast number of prisoners in Great Britain represented powerful bargaining chips used to ensure the safety and well-being of British prisoners.

When calls came through from Germany of a proposed "all for all" internee exchange, Great Britain wanted no part of it. Rather, the British government adopted a policy of exchanging prisoners on a one-to-one basis, maintaining a huge advantage over enemy nations. Britain's policy regarding civilian prisoners meant very few inmate exchanges took place during the war. Among those successfully swapped were individuals deemed unfit for military service, handfuls of internees from prominent families, and some individuals aged 45 and older.

While very limited prisoner exchanges occurred between Great Britain and Germany, enemy aliens from the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria simply ran out of luck thanks to geography. Exchange agreements never came to fruition because of the difficulties associated with arranging prisoner transportation by sea or land. That said, less than 100 prisoners from these nations remained in the British Isles during the war, which also meant they proved far from a priority for either side.

Enemy aliens in the Commonwealth also faced incarceration

Britain's dominions and colonies also got in on the imprisonment of foreigners, according to the International Encyclopedia of the First World War. These policies had especially devastating repercussions for residents of Australia. Down under, 4,500 Austro-Hungarians and 6,890 Germans faced internment based on the justification of "strengthen[ing] ... the British identity of the country." This policy involved the exclusion of all those deemed non-British, including approximately 700 German-born Australians who had become naturalized citizens in the decades leading up to World War I.

The same fate faced Germans living in other British colonies worldwide. Individuals from Southeast Asia were transported to camps in Australia for holding. Soon, the British Commonwealth redefined its social hierarchies in terms of ethnicity, national origin, and race, placing "white Britishers first, next Black Britishers, [and] last of all aliens." The relocations didn't end there.

German communities in British East Africa faced forcible relocation to India. And German missionaries serving in Palestine (then a British holding) got exiled to Egypt. Forced migrations were justified under the larger banner of "military security." But by the war's end, Germany saw things differently. In 1918, the British held 300 Germans in Egypt, 1,200 in India, 194 in the Caribbean, 1,323 in Malta, and 2,300 in South Africa. Germany contended this compelled German diaspora marked a calculated move on the part of the Allied nations to cleanse their homelands of Germans. But Great Britain and the Allies refuted such claims.

Daily life for enemy aliens felt like prison

Treatment of non-incarcerated enemy aliens also felt reminiscent of prison, per the International Encyclopedia of the First World War. Men over 55, women, and children had to abide by regulations like local curfews, registering their names with the police, and keeping clear of "prohibited areas." These rules fell under the 1914 Aliens Restriction Act and the later Orders in Council. Inevitably, they impacted nearly every aspect of life.

Those deemed enemy aliens couldn't own automobiles, cameras, motorcycles, homing pigeons, or military maps due to widespread espionage fears. They also had to avoid visiting areas deemed restricted. According to the National Archives, these laws applied not only to immigrants but also British-born women who married non-British men. In other words, had Queen Victoria and Prince Albert lived a few decades later, they would have fallen into the enemy alien category, too.

Enemy aliens who were not incarcerated wrestled with the constant threat of violence from the public. They also dealt with negative press that continued to whip up xenophobic hysteria and paint them as villains. Coupled with the incarceration of all male family members of military age, life proved anything but pleasant. Families remained broken for years, with most losing their bread-earners indefinitely. Enemy alien businesses closed, and immigrants (and the women who married them) lost their ability to travel freely. This scary and extended experience left many anxious about their futures and the outcome of the war.

From internment camps to deportation

Adding to the charges of a compulsory German diaspora were troubling figures, as reported by the International Encyclopedia of the First World War. Between 1914 and 1919, the German population in Britain dwindled from 57,500 to 22,254, and 6,150 Germans "left" Australia by 1919. During the war years, once flourishing communities of Germans disappeared in places like Bradford, Leeds, London, Manchester, Glasgow, and Liverpool.

The same happened overseas, causing great upheaval for immigrants-turned-refugees. Germany's former colonies in Africa were seized, and German settlers could no longer ascertain residency permits in most cases. Prejudice toward German immigrants was viciously wielded throughout the colonies, leaving many with no place to go. Although WWI officially ended in 1918, policies targeting enemy aliens continued with the Aliens Restriction (Amendment) Act 1919 (via the National Archives). This act imposed restrictions on employing aliens, and deportation proved commonplace once internees left prison camps.

Interestingly, as enemy aliens lost rights, other groups gained them. For example, officials extended the right to vote to groups previously excluded, including women over the age of 30 and lower-class military veterans. The result was a strange march toward democracy for some during the simultaneous disenfranchisement of others as colonial racism and anti-immigration sentiments endured. For many, this meant jumping out of the frying pan and into the fire as they transitioned from years of incarceration to deportation back to homelands crippled by war debt and guilt.