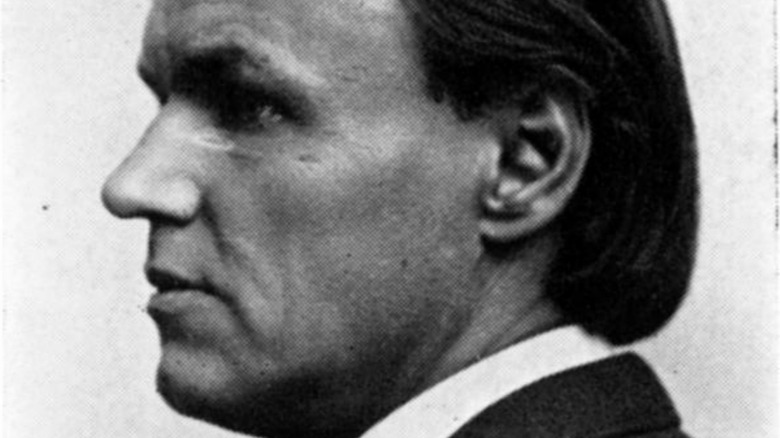

The Untold Truth Of Clarence Darrow

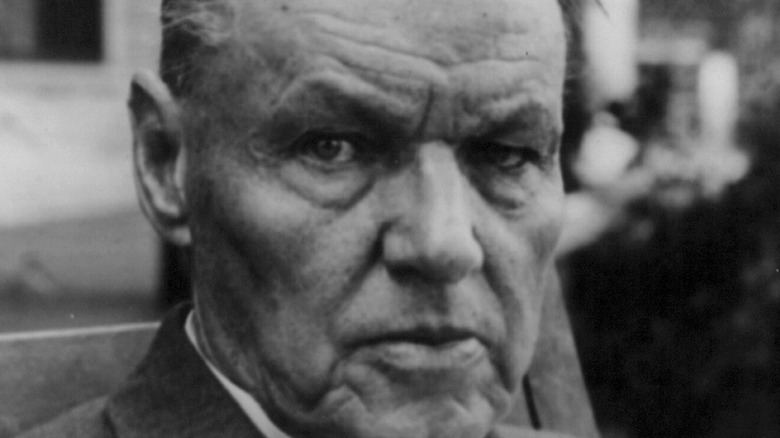

Clarence Darrow is one of the most famous lawyers in American history. The Philadelphia Inquirer has called him "the defender of the underdog." Others referred to him as the "attorney for the damned" (via University of California). Whatever people called him, though, it was clear that Clarence Darrow was a towering figure during his lifetime. In trials where he demonstrated his skills of oratory, he represented labor leaders, murderers, seditionists, and evolutionists (per Britannica). As described by Middle Tennessee State University, he fearlessly took on cases that were unpopular, taking on a mythical status in law, while making perhaps just as many enemies and admirers. He had a "passion for lost causes," The New York Times printed in 1925.

As the Chicago Reader describes him, he was both cynical and an idealist. He rejected dogmatic religions and embraced doubt as central to human progress. He had a steady, but unique rise from a simple country lawyer to a man being discussed in every newspaper across the nation. He was, in many ways, a man who was never complacent and always critical of himself and the world in which he lived. Here's his untold truth.

He grew up in a rural Ohio village of 400

Clarence Seward Darrow was born on April 18, 1857 to Amirus and Emily Darrow, the fifth of eight children (per New York Times). He grew up in Kinsman, Ohio, a small, rural village of 400 only a few miles from the Pennsylvania border. According to "The Story of My Life," Darrow's memoir, it was a tranquil and scenic place to grow up and his first fifteen years consisted almost entirely of school and playing outdoors. As described in "Clarence Darrow: American Iconoclast," the Darrow family never had much money and he wasn't particularly close to his parents or his siblings, the latter of which he would argue and fight with often.

The family lived in a unique octagon-shaped house — which is still standing today, one of 25 still in existence in Ohio, according to Business Journal Daily. It was while living here, according to his memoir, that he spent so much time reading, playing, and organizing baseball matches against children from neighboring towns. He loved baseball so much, and was so loyal to his Kinsman team, that he was shocked when he heard that there were professional players who played for money, not devotion, and would even leave to play for a rival team if it meant more money. "No Kinsman boy would any more give aid and comfort to a rival town than would a loyal soldier open a gate in the wall to let an enemy march in," Darrow recalled.

His father was the town infidel

Clarence often cited his parents as a significant influence in his life. Despite Amirus Darrow initially wanting to become a Methodist minister, by the time Clarence was born, his extremely well-read parents had both become freethinkers and rejected organized religion, which would have an important role in shaping the way in which Clarence viewed the world (per New York Times). As described in John A. Farrell's "Clarence Darrow: Attorney for the Damned," Amirus considered himself an intellectual, someone who thought in the same realm as Thomas Jefferson or Thomas Paine.

Clarence describes in his memoir how his father, who proudly became known as Kinsman's "village infidel," always had his head in the clouds (or face in a book), whereas his mother Emily was more pragmatic, had much better sense, and kept the house as well — as her husband's carpentry business — organized and operating smoothly.

Both of his parents were strongly against slavery, strongly in favor of women's rights and suffrage, and both were very gentle in their parenting, although not at all affectionate (per New York Times). Sadly, Emily Darrow succumbed to cancer while Clarence was still a teenager. He later wrote how, of his two parents, she was the more significant influence on him and, although he had forgotten much about her, he recalled her "mastering personality" and that her endless kindness and compassion for others were always guiding forces for him.

He dropped out of college twice before passing the bar

Darrow liked learning, but didn't much care for his schooling in Kinsman overall. Despite this, after his mother passed away, he enrolled at Allegheny College in Meadville, Pennsylvania, although he lasted only a year due to financial concerns (per Allegheny College). According to The New Yorker, he then secured a teaching job back home for three years while studying law on the side. Eventually, he followed his father's wishes and enrolled in law school at the University of Michigan for one year, but again left after a year and returned home due to financial concerns (per University of Minnesota Law Library). So, he took a job in a nearby law office where he could learn from a practicing lawyer, studied on his own, and eventually passed the bar exam, being admitted to the Ohio bar in 1879.

According to an interview that Darrow gave to The Harvard Crimson, even college he had found frustrating, saying that while it was certainly helpful for some people, considering the time one spent there, most people didn't get much out of it. In "The Story of My Life," he wrote how he was "appalled" by all of the wasted time in school, how he didn't find learning arithmetic useful in his adult life, found grammar rules to be inconsistent, and could never remember anything that he had been taught in his history classes. "Schools probably became general and popular because parents did not want their children about the house all day," he quipped. School had value, but needed more individualization, he believed.

He started off as a small-time Ohio lawyer

After being admitted to the Ohio bar, Darrow decided to stay close to home initially. As he describes in "The Story of My Life," he was completely broke and didn't really know too many people in law who could assist him, so he opened a practice ten miles away from Kinsman in the small community of Andover, Ohio. "I did not succeed at first," he wrote, saying that much of his lawyering during this time was related to grudges, debts, fraud, and the occasional crime. He also argued numerous cases at the Ashtabula County Common Pleas Court and even helped Andover in its quest to be recognized by the county as an official village (per Star Beacon).

In 1880, he married a neighbor and family friend named Jessie Ohl and together they had a son named Paul. Soon, they relocated to the more populated Ashtabula on the shores of Lake Erie, where he found more success. Darrow even dabbled in politics there, getting elected as the city solicitor while still practicing law (per University of Minnesota Law Library). In his memoir, he recounts how he gained valuable experience during these years in Ashtabula, as he began to improve his public speaking abilities during trials that he described as "filled with color and life and wits." He went as far as saying country lawyers, while never worth much money, were as intelligent and good of lawyers as the ones making millions of dollars in the city. By his own admission, he was quite content, but soon a city would be calling his name.

He was a corporate lawyer in Chicago before representing labor

In 1897, Darrow and his wife divorced, which he explain in "The Story of My Life" was "without any bitterness" between the two. In a later essay for Vanity Fair on divorce, Darrow would state that marriages were simply contracts and that most married couples entered into these contracts while they were very young and inexperienced in the world.

"[H]uman beings are rarely the same at forty as they were at twenty," he wrote, adding that people's emotions change as they age. As a result, Emily and Paul Darrow moved to Chicago and Clarence moved his practice there to stay close to his son.

According to PBS, Darrow secured a job as the lawyer for the powerful and profitable Chicago and Northwestern Railway. This made him a lot of money, but he felt unfulfilled, and when railroad workers went on strike, he left his cushy corporate job to represent the striking workers and union leaders. Darrow helped take the case all of the way to the Supreme Court and while the case was lost there, it put Darrow on the map as a labor lawyer (per Britannica). As described by PBS, he spent the next decade representing labor leaders and striking workers.

A scandal nearly ended his career in law

In 1912, Clarence Darrow's career as a lawyer almost came to an end due to a scandal. Darrow had been brought on to defend laborers accused of detonating a bomb near the anti-union Los Angeles Times building that killed 21 people (per University of California Library). According to the University of Minnesota Law Library, Darrow entered guilty pleas on their behalf, but as he began to recognize their guilt, he attempted to get his clients to accept a plea deal, which might be their only chance of avoiding a death sentence.

Long story short, there were bribery attempts involving the jury. According to Smithsonian, while early biographers defended Darrow against such allegations, some historians today have argued that Darrow was almost certainly involved. Esteemed biographer John A. Farrell has contended that it may never be fully known if Darrow had been involved in the briberies or not, but that ultimately, humans are complex and Darrow has to be accepted for his good and his bad. Whatever the case, Darrow was found not guilty and, according to the Los Angeles Times, a relieved Darrow promised to spend the rest of his life helping those in need.

He shifted to criminal law after the scandal

Although Darrow was acquitted of the bribery charges, organized labor wanted to avoid being associated with the scandal and distanced themselves from him. As a result, Darrow transitioned to criminal law, often representing desperate clients who were facing the death penalty. He spoke out against the death penalty often, even participating in public debates on the issue. In 1924, during one of these debates, he argued that it was the government permitting capital punishment that taught people to kill (via University of Minnesota Law School). "If a State wishes its citizens respect human life," he declared, "then the State should stop killing. It can be done in no other way."

Darrow was already relatively well-known, but one case skyrocketed him to national fame. Two teenagers named Richard Loeb and Nathan Leopold were on trial for the thrill killing of another Chicago teenager and were likely going to receive the death penalty (per Britannica). As described by PBS, Darrow knew that the evidence was already there to convict them (Leopold had lost his glasses at the crime scene), so his personal goal was simply to save the accused from death. The two were found guilty and received life sentences, but as Darrow hoped, he saved them from a death sentence. "The lives of Loeb and Leopold were saved," he wrote in his memoir. "But there was nothing before them, to the end, but stark, blank stone walls."

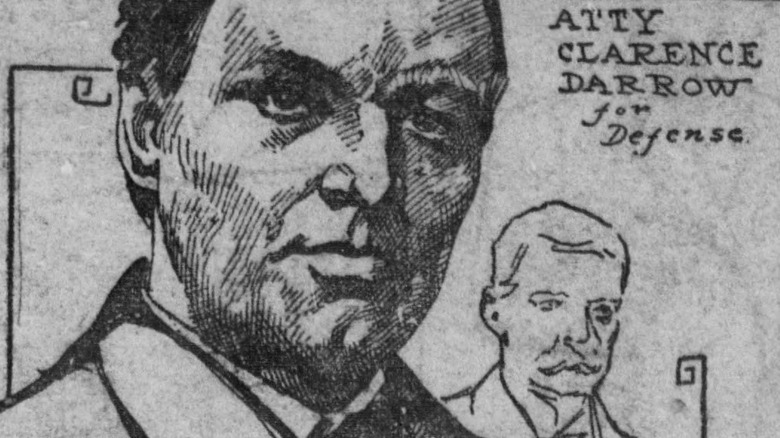

The Scopes trial made him the most famous lawyer in America

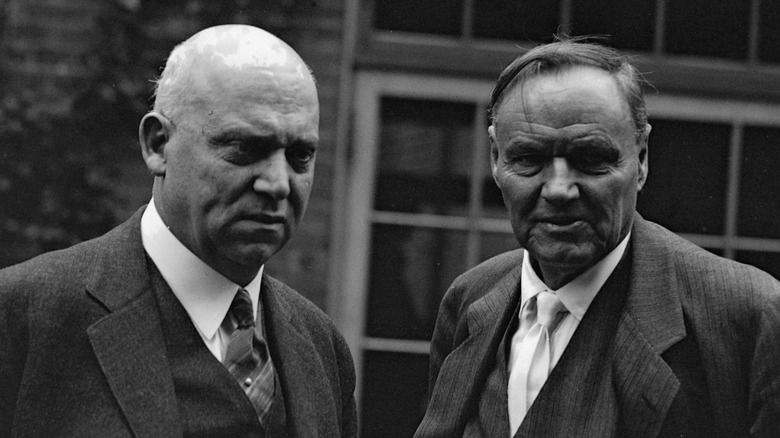

Perhaps Darrow's most famous case is what is often referred to as the "Scopes Monkey Trial." This took place in July 1925 in Dayton, Tennessee and Darrow represented a teacher named John T. Scopes who had been charged with the crime of teaching evolution to his high school students (per Britannica). Like his parents, Darrow considered himself a freethinker and identified himself as an agnostic. He also understood the challenge of taking this case in a courtroom that, according to PBS, opened with a prayer by the judge every day.

Predictably, the trial turned into a show and newspapers all across the nation covered each day's proceedings in detail. To packed courtrooms, Darrow gave long and passionate speeches as a part of his defense, declaring that such a law was a violation of the freedom of religion guaranteed by the First Amendment (per NPR). On a day that was particularly hot, the judge moved the trial outside and in front of a crowd of thousands, where Darrow questioned the prosecuting attorney William Jennings Bryan as his only witness, embarrassing him greatly as Darrow swiss-cheesed his arguments in front of rowdy spectators (via History.com). Darrow lost the case. Scopes was found guilty. Yet, this skyrocketed Darrow's superstar into the most well-known lawyer in the United States of America.

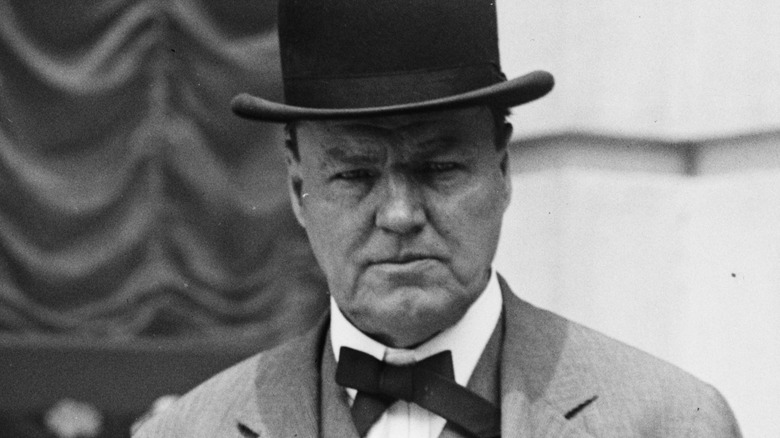

He and William Jennings Bryan had a long and complicated history

Interestingly, Clarence Darrow and William Jennings Bryan had a complicated history going back years before they went toe-to-toe in the Scopes Monkey Trial. In 1896, Bryan had run for president as a populist candidate for the Democratic Party and Darrow had publicly supported him, although even then he privately criticized him for his strict religious beliefs, according to PBS. In "The Story of My Life," Darrow recollected meeting Bryan during this time and how, despite their religious differences, he found he agreed with him on many issues and he would go on to support him again in his 1900 campaign. After being asked by Bryan to help him campaign again for his third run in 1908 though, Darrow took a vacation instead. Bryan lost again.

That history was clear when they met again at trial. Darrow alleged in his memoir that Bryan wasn't there to represent the actual case, but to represent Christianity. While Bryan lost the case, he had lost, in some eyes, the court of public opinion after Darrow's humiliating questioning. Five days after the Scopes verdict, William Bryan Jennings went to sleep. He suffered a stroke and never woke up (per History.com). As described by PBS, some even accused Darrow of murdering Bryan due to the cruelty of his questioning during the trial.

The Ossian Sweet case made Darrow a civil rights hero

Race relations were extremely volatile throughout the United States during the 1920s. Somewhere between two and five million white Americans were in the Ku Klux Klan (per The Atlantic). As detailed by the NAACP, lynchings of Black Americans, particularly in southern states, were still common. In most places, segregation was still the rule, not the exception. It was in the midst of this that Clarence Darrow took on one of his other most famous cases: the defense of Dr. Ossian Sweet and his family. As described by the Detroit Historical Society, Sweet was a distinguished and well-known Black doctor who bought a house in an otherwise all-white community in Detroit. This led to a white mob of hundreds outside of his house. When someone within the house fired a gun into the crowd, killing one and injuring another, every person in the household was arrested and charged with murder.

In "Clarence Darrow: American Iconoclast," author Andrew E. Kersten explains that the NAACP pursued Darrow for the defense partially due to his fame: it'd help bring national attention to the case. Darrow was initially reluctant as he was leaning towards retirement, but took on the case anyway. He was described as brilliant during the trial, particularly the cross-examinations. In his own recollection, it revealed the hypocrisy of white northerners who went to church every Sunday, yet couldn't practice what was preached. It resulted in a mistrial. The second trial resulted in an acquittal. Darrow wrote that this was one of the cases for which he was most proud and stated that he was not resentful against the white community, only the racism that they had been taught.

He was a staunch agnostic

Clarence Darrow was not shy about sharing his views on religion. He was agnostic and viewed organized religion quite negatively. He wrote about it, he debated it, he talked about it publicly. In a lecture titled "Why I Am Agnostic," Darrow argued that to be agnostic simply meant that one had doubt and to be doubtful and skeptical was how humans progressed. He criticized all religions, but often pointed to Christianity specifically being the dominant religion in the United States. He'd offend audiences by mocking the Bible, pointing out its contradictions and inconsistencies. "Strictly speaking, there is no such book [as the Bible]," he told the audience. "These [sixty-six] books were written by many people at different times."

He didn't shy away from these beliefs in "The Story of My Life" either. He wrote an entire chapter on why he was agnostic called "Questions Without Answers," where he works through a series of dozens of questions that he deemed impossible to answer by man. "When we abandon the thought of immortality we at least have cast out fear," he maintained, adding that there was self-respect gained by recognizing the life one lived was likely all there was. In a letter to a friend, he stated that he wasn't an outright atheist, but that he couldn't believe something without evidence and he had never been presented with any that had convinced him.

The Great Depression crushed his finances

One of the reasons that Darrow continued to write, speak, and lecture, even after retiring from law was that the Great Depression had crushed his finances. According to biographer John A. Farrell, he had lost almost his entire life savings in the stock market crash after finally being financially secure for the first time in his life (per Boston.com). According to the University of Minnesota Law School, Darrow and his son Paul's stocks were estimated to be $300,000 before the crash ... only to fall in value to $10,000 afterwards. "Clarence Darrow: American Iconoclast" details how Darrow had actually predicted the crash was coming, but Paul had been the one who held onto them too long and, indeed, Clarence did blame his son for the loss.

In his memoir (which was actually written during this financially difficult time), Darrow explained that this is also why he took on some of the more unlikely cases in his later law career. He simply needed the money. In a private letter, he insisted to a friend that he wasn't broke, but that he didn't want to end up dependent on anyone.

He wrote numerous books throughout his life

Besides "The Story of My Life," his memoir first published in 1932, Darrow wrote quite a few books over the course of his lifetime. In 1904, he published his first book: a semi-autobiographical novel called "Farmington" from the perspective of a character named John Smith. The book was published the year that his father died and the father played a major role in the opening chapters of the book. The character of John was quite clearly based on Clarence himself. According to "Clarence Darrow: Attorney for the Damned," the book was based on growing up in Kinsman and was actually a critique of the values held by so many in small towns. Another book, published in 1905, was a work of fiction titled "An Eye for an Eye." It followed a character named Jim Jackson and traces his story to how he ended up on death row. They weren't commercially successful books, but they put him in good literary company. He ended up forming an organization called the Intercollegiate Socialist Society with authors Jack London and Upton Sinclair (per University of Michigan).

Darrow otherwise stuck mostly to essays and nonfiction. In 1902, he published a critique of the U.S. prison system and capital punishment with "Resist Not Evil." Most of everything else he published was also related to crime, justice, law, and the criminal justice system.

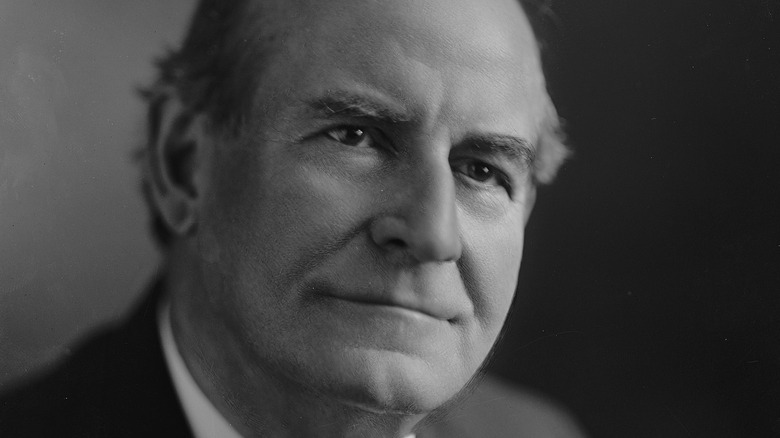

Nearing death he doubted his entire career

Pessimism was increasingly a driving force of Darrow's worldview as he aged, so it should come as no surprise that near the end of his life, he openly doubted that he had accomplished much of anything worthwhile throughout his eight decades of living. Approaching his seventies, he published an essay based on a lecture of his titled "Facing Life Fearlessly: The Pessimistic Versus the Optimistic View of Life." In it, he maintained the pessimists had better and more realistic views of the world and were better equipped to handle adversity. "I wouldn't want to be an optimist because when I fell I would fall such a terribly long way," he wrote. "The wise man trains for ill and not for good." He argued that was life was pleasant sometimes, it was filled with tragedy and the pessimist was better prepared.

He wrote in his memoir that he didn't necessarily have regrets, as he felt that those were vain, but he questioned if he had done enough over his life. He noted that he appreciated the simply pleasures of life each day that he awoke, but he wondered whether there was any point to it all. "It is possible that no life is of much value," he considered, "and that every death is little loss to a world that seems bent on its way." Darrow died on March 13, 1938. He was 80 years old. In his New York Times obituary, they described him as "one who thoroughly understood human nature yet loved his fellow-man." Perhaps for someone like Darrow, there could be no better compliment.