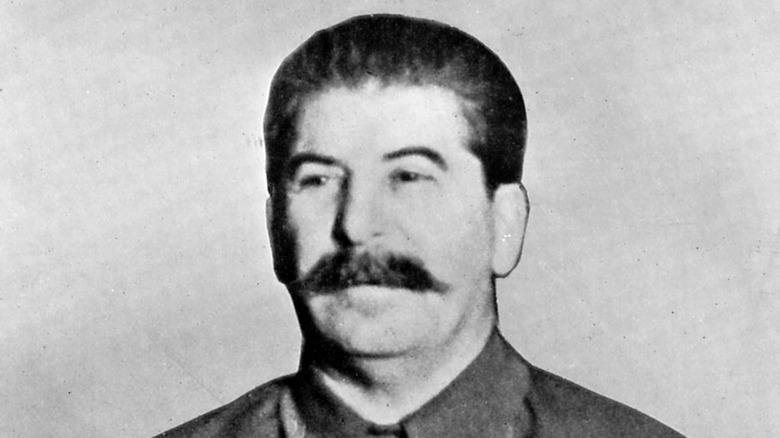

The Tragic 1962 Death Of Joseph Stalin's Son, Vasily Stalin

Though Joseph Stalin is one of the most infamous historical figures of all time, far less known is the story of his son, Vasily. Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the cold and brutal personality of his father, Vasily did not grow up to become a well-adjusted heir apparent to Stalin's dictatorship. Rather, he had an unhappy childhood that resulted in an equally unhappy death at around just 40 years old.

Even from the beginning, Vasily's childhood was filled with trauma and abuse. Vasily's mother, Nadezhda Alliluyeva, had a contentious relationship with Stalin, with multiple allegations of the dictator's emotional and physical abuse. According to Rosamond Richardson's book "The Long Shadow: Inside Stalin's Family," Alliluyeva tried to separate from Stalin, but was ultimately convinced to stay in the marriage. Part of the reason was because of her fondness for her son. Richardson quotes Vasily's sister, Svetlana, as saying that Alliluyeva "adored" him, despite seeing obvious behavioral issues. For example, Vasily would destroy his sister's toys; another source claimed that Vasily would do "strange" things, including hurting animals.

Eventually, the strain in Alliluyeva and Stalin's marriage became too much, and she committed suicide in 1932, per United Press International. Vasily was just 11 years old.

The seeds of a spoiled and debauched life

Vasily continued in his schooling, despite the personal tragedy. According to Rupert Colley, historian and author of "The Savage Years: Tales from the 20th Century," Vasily was a poor student, relying on his famous last name more than his intellect. However, he kept advancing in his career, and at 17 years old, he joined the Myasnikov Aviation School, an admittance that was facilitated by his father's aides. However, even aviation school did not provide the stern guidance that Vasily needed. He continued to receive preferential treatment, both as a matter of course and through his own request. For example, he slept in his own private quarters, versus the everyman's barracks, and ate with the officers.

However, Vasily's actions ended up on the radar of his father, who heartily disapproved of his son's behavior. Stalin even went so far as to deem his son a "spoilt boy of average abilities, a little savage ... and not also truthful." The dictator reportedly requested that instructors be stricter with his son and end all special treatment in a letter to "teacher comrade Martyshin" (via the Library of Mikhail Grachev).

But while Vasily's alleged behavior was undoubtedly petulant and manipulative, some of his actions also suggest some serious mental health issues. For example, Vasily is described as often threatening suicide to get his way — a move indicative of a deeply unhappy person.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

The spiral continues

Despite his underwhelming talents and boorish behavior, Vasily managed both to graduate and rise in the ranks of the air force. According to Rupert Colley, he was drinking heavily at the time and would often fly while inebriated. His sister Svetlana deemed him a full-fledged "alcoholic" by this point in her memoir "Twenty Letters to a Friend" (via The New York Times).

When World War II broke out, he continued to be promoted beyond his talents. "[Vasily] was pushed higher and higher. Those responsible couldn't have cared less about his strengths and weaknesses. Their one thought was to curry favor with my father. Yet he could no longer fly his own plane. My father saw the state he was in," she wrote.

By 1952, Vasily's ineptitude reached a breaking point. He was serving as the Air Force Commander of the Moscow Military District and went against orders to continue a planned air show, despite cloudy weather. According to Svetlana, the result was a total disaster, with many planes coming close to ruining buildings and several pilots crashing due to the poor visibility. It was at this point that Stalin himself removed Vasily from the prestigious post. In despair, Vasily descended deeper into alcohol abuse.

If you or anyone you know needs help with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

The knives come out after Stalin's death

Vasily's behavior during his time in the armed forces unsurprisingly made him a deeply unpopular figure among his men. As a result, Vasily became more and more paranoid about his fate after his father's death. "Khrushchev, Beria, [and] Bulganin'll tear me apart," he reportedly lamented (per City Journal). He was not wrong.

As noted by Smithsonian Magazine, Joseph Stalin died in March 1953, reportedly of a stroke. However, rumors of murder ran rampant, and Vasily believed the conspiracy theories. However, instead of dealing with his doubts quietly, Vasily decided to be vocal about them. He openly discussed how his father might have been poisoned or that the doctors did not administer proper care. "He ranted and raved ... if anyone had megalomania, it was he," Svetlana recalled (via The New York Times).

Due to his public outbursts, he was summoned by the Ministry of Defense. During this meeting, Vasily was allegedly asked to be more discrete about his opinions and was even offered a new military position as a peace offering. However, it was not as prestigious as his role in Moscow, and Vasily turned it down. This was seen as a rejection of a direct order, and Vasily was summarily arrested. The knives were coming out.

Imprisonment and madness

After his arrest, Vasily was put on trial, and the results were not pretty. Vasily was no longer under the (albeit distant) protection of his father; moreover, considering the standards of justice in Soviet Russia at the time, he could not have expected to receive a fair hearing even if he were innocent.

That said, many things that came out during this time were appalling. According to his sister's book, excerpted in The New York Times, several soldiers claimed that he had used physical violence against them. He had relied on "intrigues" that caused both the arrest and even death of innocent men. He was accused of using public funds for private expenses. Even the Minister of Defense testified against him.

At the end of the trial, Vasily was sentenced to eight years in prison. The shock took an even greater toll on his mental health, and he drifted in and out of military hospitals and sanatoriums. He was eventually released one year early, but was unable to turn his life around and remained addicted to alcohol.

Vasily's tragic death

After Vasily's release from prison, he fell in with shady types and had a bender where he "vanished" for five days; his sister later found out that he had been staying with a woman who worked as a railroad switchman (per her book excerpt in The New York Times). Due to his drinking and unstable behavior, he quickly found himself in jail yet again. Though the exact cause was unverified, there are rumors that it was due to a drunk driving accident that killed a woman (via Time).

After this second stint in jail, Vasily was sent far from Moscow to Kazan, the capital of the Tartar Autonomous Republic. According to a local Kazan news source, he was flanked by KGB agents and lived in a modest apartment for around a year. It was then that he suffered from a suspected heart attack, as noted in an archived 1962 article from The New York Times. The heart "ailment" was likely a consequence of his excessive drinking.

Around 300 people showed up to Vasily's funeral, though most were curious spectators from nearby homes rather than mourners. In total, just 400 rubles were spent on the funeral — the rough equivalent (per Historical Currency Converter) of around $765 today. The low cost of his funeral was not the only slight against Vasily in death. His sister, Svetlana, publicly claimed in her book that he was "disgraced" and "[died] a drunkard" as a harsh final farewell to his life.