The Messed Up Truth Of The British Empire

Once upon a time, the British Empire, which began cementing its global footing during the 16th century, ruled as the world's greatest imperial power. After the handover of Hong Kong in July 1997, the once ever-present superpower became a fixture restrained to the pages of history, with much of these pages ornately highlighting the heroic and "civilized" missions it undertook across the world at the zenith of its power. The truth is more complicated. Yes, the British Empire abolished slavery before certain rivals like the newly formed United States, but only while making sure over 40,000 slave owners were financially compensated. Yes, in 1829, British authorities outlawed the Hindu practice of sati – the burning of widows as they sit atop their husbands' funeral pyres — in India, all while draining the region of precious resources for the benefit of the crown and leaving it vulnerable to the horrific famine of 1876-1878 that killed millions.

The pervasive myth of a genial British Empire that carried with it a benevolent nature wherever it sailed must always be scrutinized and dispelled. Like any other imperial conqueror that ever existed, it was a ruthless and colossal force, as its long and bloody history proved century after century. From utilizing brutal tactics to crush countless revolts across its colonies, to venomously targeting a population's very cultural identity, to doing little to alleviate the famines that occurred in the regions they occupied, the history of the British Empire is simply messed up.

The suppression of the Irish language under British rule

The Irish language is one of the world's oldest languages, with a history that traces back to at least the fifth century. Unfortunately, the number of fluent speakers is dwindling today; the 2022 Irish census reported that out of nearly 2 million Irish speakers — Ireland has a population of over 5 million — only 10% felt comfortable claiming fluency in the language.

The tragic downward trajectory of such an ancient language can be unequivocally attributed to British occupation of the Emerald Isle. While English rule over Ireland may have officially been cemented in 1541, systematic suppression of the Irish language began centuries earlier. In 1366, Prince Lionel, the son of Edward III, put into law the infamous Statute of Kilkenny, which banned Anglo settlers from speaking the Irish language and imposed a host of other rulings that treated every single facet of Irish culture as a disease that needed to be contained. Four hundred years later, as Britain became the center of the world, the Administration of Justice (Language) Act was passed in Ireland, which outlawed any language but English spoken in the courtroom.

By the early 1900s, the mere funding of efforts to teach the Irish language in schools was often considered a nationalistic affront to unionist ideals. After the failed Easter Rising in 1916, when Eoin MacNeill, the chief of staff of the Irish Volunteers and a scholar whose life and career was largely dedicated to the Irish language, faced a series of arrests, British authorities made it a point to confiscate his linguistic and historical research. Simply put, throughout its existence, the British Empire always viewed the Irish language as a threat, and the results can be plainly seen today.

The British Empire failed to properly alleviate the suffering caused by the Irish Potato Famine

The Irish Potato Famine, which saw a mold (Phytophthora infestans) absolutely ravage the region's most utilized crop, lasted from 1845 to 1852. Around 1 million people died from the resulting disease and starvation; millions more fled. While the British Empire was not directly responsible for the blight that devastated the land, imperial policies did little, if anything, to halt the suffering of the Irish people.

Even as a horrific scourge swept through Ireland, appalling amounts of food and grain were still being shipped out to England. Further adding oil to an inferno of a crisis was the way Irish society was set up at the time, courtesy of the British. The land-owning elite in Ireland were mainly Anglo-Irish landlords who managed their properties from afar and rarely paid heed to their estates. This led to a bureaucratic nightmare as countless people starved; whose responsibility was it to help the Irish people — negligent landlords or the British Parliament?

At the helm of this petty British bureaucracy stood Sir Charles Trevelyan, the official in charge of government relief efforts in Ireland during the famine. Trevelyan's beliefs, which were seemingly layered with the credence that the famine was some sort of divine punishment on the Irish people and rooted in the power of free enterprise, did little to halt the mass starvation. His appointment was nothing more than a dagger to Irish hope.

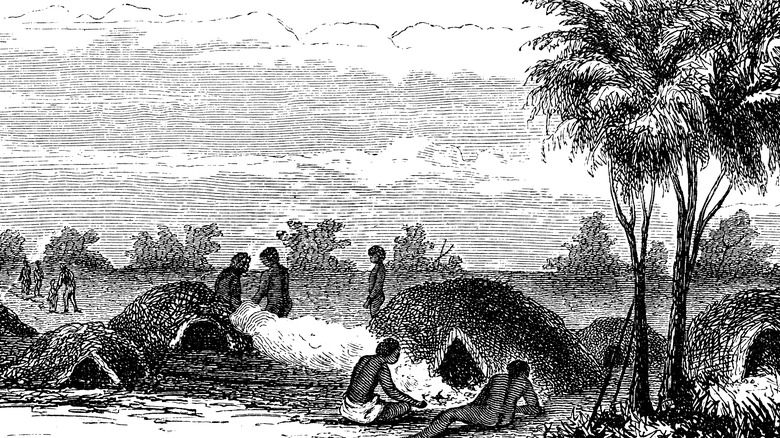

British expansionism and Australia's Aboriginal peoples

The countless mass killings of Australia's native Aboriginal people serves as one of the many dark chapters strewn across the British Empire's scarlet history.

The British defeat during the American Revolution helped exacerbate a serious problem back in the land of King George III — the country's prisons were severely overcrowded, and the empire no longer had access to the additional space that their former colony offered. This led to a frantic search for another location that could house a significant portion of the British prison population. Thus, imperial expansionism into Australia, at the harrowing cost of the continent's native Aboriginal population, started. Colonial settlement first began in January 1788, with Captain Arthur Phillip at the helm of a modest fleet transporting the first batch of prisoners.

Large-scale massacres of Indigenous people began a few years later. By 1794, British troops began carrying out the first wave of mass killings before eventually relying on the combined and localized might of colonial settlers and regional police, whom often operated with governmental support. Such attacks on the Aboriginal people continued with legal impunity until the 1920s. (The Myall Creek massacre, which saw the murder of at least 28 Wirrayaraay people in June 1838, is famous due to it being the sole instance of British settlers being tried and found guilty for killing Aboriginal people.) From 1794 to 1928, it's estimated that over 400 massacres occurred on the Australian Colonial Frontier. During this period, from these calculated and government-sponsored offensives alone, Aboriginal casualties reached over 10,000.

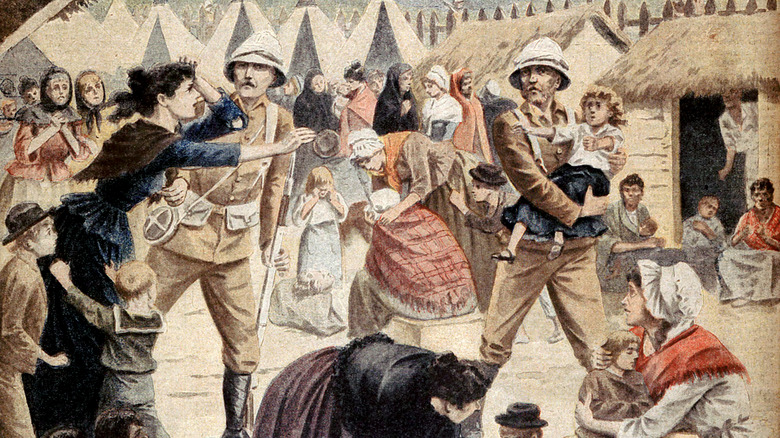

The British Empire's concentration camps during the Second Anglo-Boer War

The British Empire implemented what some refer to as the first modern concentration camps during the Second Boer War in South Africa. The conflict, which lasted from 1899 to 1902, saw British troops enact drastic measures against Boer (descendants of Dutch colonists) guerilla movements. By 1900, imperial forces relocated over 200,000 civilians, most of whom were women and children, into camps.

The horrid conditions of the camps, which were marked with severe starvation and widespread disease, were famously described by English anti-war activist Emily Hobhouse. "There are nearly 2,000 people in this one camp ... over 900 children ... Imagine the heat outside the tents and the suffocation inside! We sat on their khaki blankets ... the sun blazed through the single canvas and the flies lay thick and black on everything; no chair, no table, nor any room for such" (per The Guardian).

By the war's end, at least 28,000 Boers perished in the camps, with the majority of the casualties being children. While extensive records were not kept regarding the deaths of Black prisoners detained in separate camps, it's believed over 20,000 died.

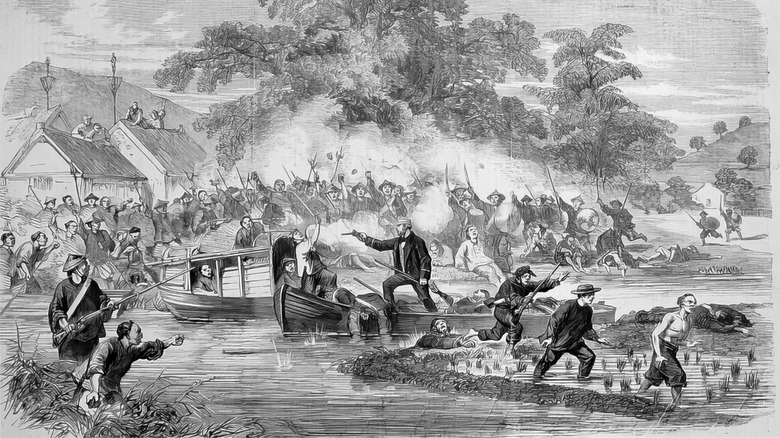

The British Empire's forgotten role in the Opium Wars

The Opium Wars of the 1800s helped illustrate just how far the West, especially Great Britain, would go when it came to securing what it deemed invaluable trade.

During the 19th century, the British Empire was involved in lucrative trade with China. Valuable Chinese goods such as porcelain, silk, and tea flowed into Britain. However, the Western power faced a pair of glaring issues when it came to their Eastern trading partner. For starters, British vessels were restricted solely to Canton (modern-day Guangzhou). Chinese merchants also continuously expressed disinterest in British goods and only demanded silver in return. For the British Empire, this created a panic as it found itself constantly tapping into its silver reserves. The imperial response to this issue? Illegally smuggle Indian opium into China and sell it for silver. Opium had been banned in China since 1796. Decades later, opium addiction in the country reached alarming levels, getting to the point where British smugglers were bringing in over 1,000 tons of the drug into China every year.

China found itself embroiled in a pair of wars with Britain (with the latter being joined by the United States, Russia, and France in the second conflict) after it attempted to push back and implement safeguards against illegal opium importation. Those conflicts would see China lose large amounts of territory, global standing, and control of its own markets.

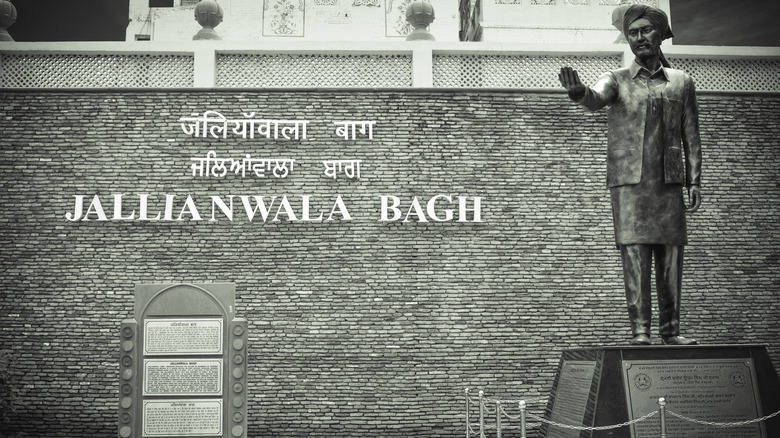

The Jallianwala Bagh Massacre

In April 1919, the British Empire committed an atrocious act that would fundamentally change its rule over India and put the country on the path to independence. The Jallianwala Bagh massacre, or the Amritsar massacre, as it's also known, occurred when a group of Indian nationalists rallied in the holy city of Amritsar at the Jallianwala Bagh park to protest British rule, specifically, the Empire's forced conscription of Indian troops and the heavy taxes it consistently levied from the people. (It's important to note that during this time, there was also mass outrage toward the Rowlatt Act, legislation that gave imperial authorities the right to conduct trials without juries and imprison suspects without them first pleading their cases in court.)

Prior to the massacre, amid rising tensions in the Punjab region, British Brigadier General Reginald Dyer took command of Amritsar. With martial law in effect, freedom of assembly was banned. However, on April 13, 1919, thousands traveled to the city for the Baisakhi festival, a traditional Sikh harvest celebration, and happened to join the demonstrators at Jallianwala Bagh. This resulted in Dyer leading his troops to the park and surrounding it, where they then began firing on the unarmed crowd until over 1,600 rounds of ammunition had been spent. Afterward, official British sources maintained a death toll of 379. However, the number is likely higher, with hundreds more wounded from the massacre.

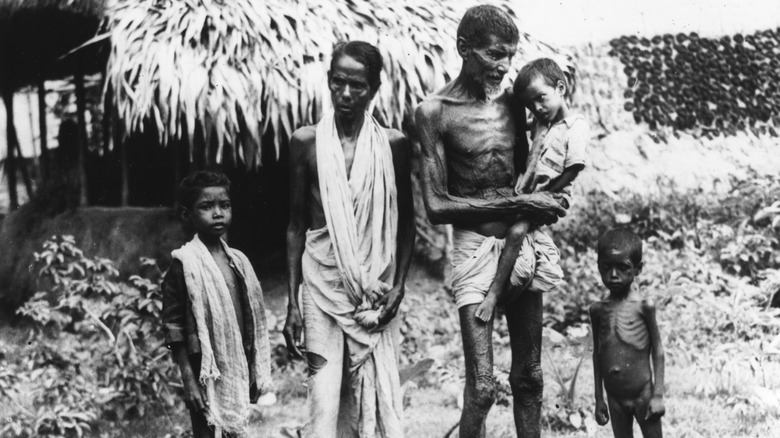

The Bengal Famine of 1943

In 1943, while the nightmare of World War II engulfed the globe, one of the biggest famines in world history occurred in eastern India, taking the lives of over 3 million people. Unlike the Great Potato Famine in Ireland, the direct causes for the Bengal Famine of 1943 are primarily considered to be more economic and political in nature, with wartime pressure seeing the British Empire divert massive amounts of food (such as rice, an item that suddenly became gold after the Japanese invasion of Burma) to various warfronts.

Inflation, widespread panic, routine transfer of valuable exports, and general imperial indifference to the repeated warnings that the situation in Bengal could leave the region susceptible to famine all contributed to paving the road to catastrophe. According to Leo Amery, the secretary of state for India at the time, Winston Churchill's initial reply to the crisis was one of cold dismissiveness, with the prime minister making a point to place blame on Indians for "breeding like rabbits." While more serious attempts at relief efforts began to form at the end of 1943, the ultimate tragedy had already taken countless lives.

In recent years, the horrors of the famine, which were traditionally treated as a mere footnote in the history of World War II, have finally been given more scholarly attention and deserving recognition. In an account published by the BBC, Niratan Bedwa, a survivor of the famine, described the trauma families were forced to endure. "Mothers didn't have any breast milk. Their bodies had become all bones, no flesh," she explained. "Many children died at birth, their mothers too. Even those that were born healthy died young from hunger. Lots of women killed themselves at that time."

The bombing of Iraq in 1920

In 1920, a revolution broke out in Iraq. More than 100,000 Shia and Sunnis banded together to rebel against the British military, which had occupied Iraq since the end of World War I. While the British may have seen themselves as liberators who freed the Arabs from the yoke of the Ottoman Empire, the Iraqi people quickly grew dissatisfied with yet another imperial power controlling and dictating every facet of their society.

Insurgency groups, which included Kurdish fighters as well, picked their targets wisely: railway lines and isolated imperial military posts. The revolts also displayed a fascinating level of class unity on top of their religious diversity, as Iraqi revolutionaries seemed to come from all walks of life. Rural tribesmen to urbanites, it mattered not; the British had managed to greatly anger a majority of the population.

The British used the uprising as an opportunity to brutally showcase the terrifying power of the Royal Air Force. According to The Guardian, in 1920 alone, the RAF racked up over 4,000 hours of flight time in Iraq and dropped a staggering amount of bombs (nearly 100 tons), with Iraqi casualties reaching close to 9,000. For the next several years, control of the region would be heavily reliant on a continuous wave of air raids, with RAF commanders applying a hawkish focus on villages.

The Partition of India

Simply put, the British handling of the 1947 Partition of India has to be considered one of the biggest and most grotesque geopolitical botches of modern history. The aftermath of World War II saw Great Britain seemingly eager to begin walking the path of decolonization; this meant carelessly tackling the Hindu-Muslim divide during the rise of India and Pakistan's independence with a stark and hurried indifference. The British-led partition – led by a British lawyer who never set foot in India — drew up arbitrary territorial boundaries that suddenly separated families and carved through non-homogenous communities of Muslims and Hindus.

In a 2017 interview with The Washington Post, Sarjit Singh Chowdhary, a Sikh soldier of the British army who fought in Iraq and later aided Muslims escaping to Pakistan, described the immediate mayhem that engulfed the subcontinent after the partition. "When I had left, India was a peaceful country," Chowdhary explained. "When I came back, it was bloodshed." In the mere months after the partition, the region descended into unrivaled calamity. Seemingly overnight, nearly 20 million people became migrants as they attempted to flee to either side of the new borders, with "blood trains" — trains filled with slain passengers — becoming commonplace.

In the end, the story of Britain's hasty withdrawal from India is one that ended with burning, looting, massacres, and countless cases of rape. Records indicate that at least 2 million people died in the upheaval that followed the partition.

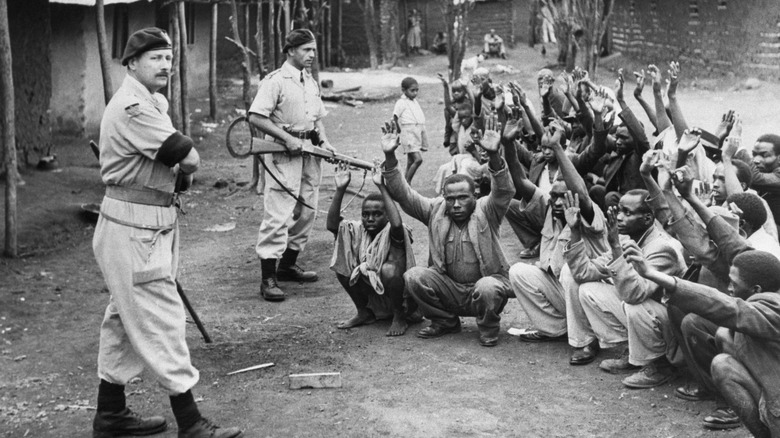

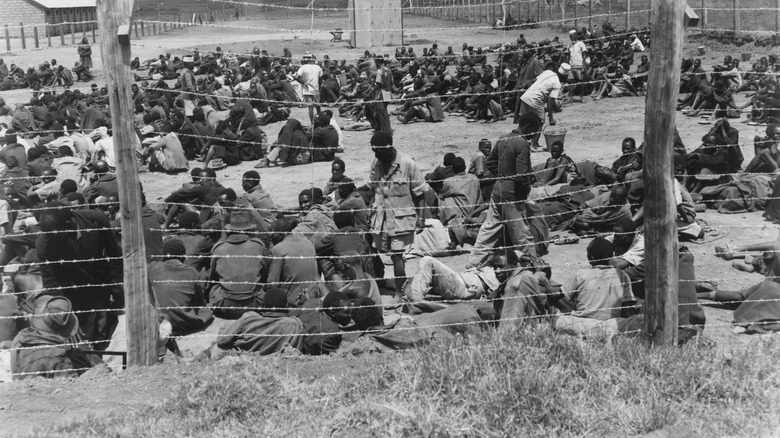

The British terror in Kenya

From 1952 to 1960, Kenya was engulfed in a bitter conflict known as the Mau Mau rebellion (also referred to as the Mau Mau uprising and the Kenya Emergency). Mau Mau forces, primarily consisting of Kikuyu people, fought against British rule in Kenya, which saw a series of horrific imperial reprisals.

The Kenya Human Rights Commission maintains that 90,000 Kenyans were killed or tortured during the conflict, with another 160,000 jailed in hellish conditions. The works of Caroline Elkins, author of "Imperial Reckoning: The Untold Story of Britain's Gulag in Kenya" and "Legacy of Violence: A History of the British Empire," offer further insight on Great Britain's actions in Kenya by highlighting how the Empire once again relied on camps to quell African resistance. In "Imperial Reckoning," Elkins wrote that "Only by detaining nearly the entire Kikuyu population of 1.5 million people and physically and psychologically atomizing its men, women, and children could colonial authority be restored and the civilizing mission reinstated."

While British loyalist forces emerged victorious in the war, the brutal nature of the conflict helped pave the way for a complete Kenyan independence in 1963. Allegations of wide-scale torture, forced relocation, imprisonment without trial, and a host of other flagrant human rights violations employed by imperial authorities continue to follow the British government into the present-day. In fact, half a century after the end of the Mau Mau uprising, the conflict in Kenya would help reveal just how far the Empire would go to keep their secrets forever buried.

Operation Legacy – the ultimate British coverup

As the collapse of the British Empire neared, London officials looked to make sure certain dirty imperial secrets remained forever under lock and key. Between the 1950s and 1970s, as Great Britain's global standing and control of its remaining colonies began to wane, the once-mighty empire worked tirelessly to compile a mountainous trove of sensitive documents highlighting the endless column of atrocities committed against colonial subjects across the globe.

This scheme would later be revealed to be an official government policy dubbed "Operation Legacy," a program hellbent on maintaining the secrecy of certain documents that could offer irrefutable evidence against the British Empire and amplify the voices of the colonies it once ruled. Instructions on how best to remove certain documents were meticulous; if they were not burned or secretly sent back to England, they'd be dropped in the ocean.

Light began being shed on Operation Legacy after four elderly Kenyans — who claimed to have undergone brutal torture at the hands of British forces during the Mau Mau rebellion — were legally granted the right to pursue compensation from the British government in 2011. Two years later, the British government agreed to pay nearly £20 million to over 5,000 Kenyan torture victims. Additional lawsuits alleging colonial land theft have followed, proving that the British Empire's once ruthless and never-ending reach is still being felt to this day.