The Tragedy Of Jesus Explained

Among the central themes of Christian art, especially of the golden artistic eras of the Renaissance and Baroque, were the tragedies of Jesus' life. Michelangelo's La Pieta, probably the exemplar of sculpture, showed Mary lovingly holding her dead son in her arms. Painters depicted her weeping over Jesus' death at the foot of the Cross or Christ praying over his stepfather. St. Joseph. The artistic focus on the tragic aspects of Jesus' life should not be viewed as a morbid curiosity — they were the artistic re-imaginings of the cornerstone concepts of their Christian faith.

At the core of Christian belief is that Jesus' life was meant to be tragic. He told his followers that, even before his was crucified, they would be expected to take up their crosses and follow him on the hard road of suffering, as God did not ask others to suffer for him without first suffering for them. By enduring tragedy and death in love, Christ is said to have conquered both. Thus, literally and figuratively, Jesus' tragedies and suffering became the path to eternal life with God in Heaven. From being a fugitive at birth to an excruciating death, and all manner of sad events in between, here's a run-down of the tragedy of Jesus.

He lost St. Joseph as a young man

Walk into any Catholic church and you will encounter a statue of St. Joseph holding baby Jesus in one hand and a lily in the other. The Bible itself, however, is silent on their relationship. In fact, St. Joseph doesn't have a single recorded line, probably because he died around a decade before Jesus began his ministry, when Jesus was in his late teens/early 20s. Instead, the relationship is extrapolated from apocryphal extra-biblical traditions of St. Joseph's death, which stress Jesus' grief at losing him.

This main source, apart from popular tradition, is the apocryphal text "The Story of Joseph the Carpenter" (via The Catholic Encyclopedia). The text, which is mostly told from Jesus' perspective, depicts a tender, loving relationship. As the 111-year-old Joseph lay sick and dying, Christ and the Virgin Mary prayed over him. Jesus beseeched God, "... hearken to my prayers and supplications on behalf of the old man Joseph ... let their [the angels] whole array walk with the soul of my father Joseph, until they shall have conducted it to You."

After Jesus invoked blessings upon Joseph, whom he reverently called his father, Joseph died. After, "Having thus spoken, I embraced the body of my father Joseph, and wept over it; and they opened the door of the tomb, and placed his body in it, near the body of his father Jacob." The tradition survived for generations of painters to imagine and depict, such as the above exemplar from Italy.

King Herod Antipas executed his relative John the Baptist

Jesus faced a family tragedy when Judean King Herod Antipas executed John the Baptist. According to Matthew 14:1-12, Herod beheaded John the Baptist at the behest of Herodias — whom he had recently married amongst great controversy — a tradition that Jewish historian Josephus reliably corroborated, despite some flaky dating. Unfortunately, neither Josephus nor the Bible describe Jesus' personal relationship with John the Baptist. Luke 1:36-39 says they were kinsmen — the Virgin Mary and St. Elizabeth (John's mother) were relatives. But it doesn't say whether the two were close or even knew each other. In fact, John 1:31 says John "did not know" Jesus when the latter appeared for baptism — their only recorded interaction.

Despite their seemingly distant relationship, the Bible records that Jesus was deeply affected by this family tragedy; his reaction is a familiar one to modern ears. Matthew 14:13 says, "When Jesus heard of it, he withdrew in a boat to a deserted place by himself." Thus, according to the Bible, Jesus was crushed. Was it due to the loss of a relative, the death of a holy man, or both? The former would not be expected if they hardly knew each other. Thus, artists from across Christian history imagined that they grew up together from their earliest days. It is not uncommon to see paintings of Mary with two babies: John the Baptist and Jesus, who are sometimes shown in a loving embrace, like in Italian Renaissance painter Marco Palmezzano's work pictured above.

Pontius Pilate murdered his fellow Galileans

Jesus' opinion of the Roman government of Judea is difficult to parse from the Bible, but given Pontius Pilate's reputation for brutality and anti-Jewish sentiment, one would expect Jesus to have denounced him. Instead, he tells his disciples, "... repay to Caesar what belongs to Caesar and to God what belongs to God" in Matthew 22:21.

The only mention of a massacre that might have affected Jesus personally appears in Luke 13:1-5. A group of Jews questioned him about Pilate's killing of a group of Galilean pilgrims, described as "Galileans whose blood Pilate had mingled with the blood of their sacrifices." It is heavily implied that the pilgrims, who would have been Jesus' co-ethnics from northern Israel, were massacred in the Temple — Judaism's holy of holies and the only place where Mosaic Law permitted sacrifices to take place.

Jesus' reaction is quite muted in the verse, with the massacre being secondary to a call for repentance. Furthermore, the date of the massacre is not identified, so it is unclear whether it had happened years before. But had it taken place in the Temple, the massacre at the hands of the pagan Romans would have been sacrilege, as the Temple of Jerusalem was God's house. Jesus made his attitudes towards anything resembling sacrilege crystal-clear in John 2:16, driving the moneychangers out of the Temple for "making [his] Father's house a marketplace."

His lot was to have a target on his back

It's fair to say that Jesus was targeted from day one, when King Herod of Judea tried to kill him as a baby after the magi referred to Christ as "King of the Jews." Later in his life, the Pharisees tried to stone him, the high priests arrested him, and Pontius Pilate crucified him, despite admitting Jesus had not committed any capital crime.

Jesus' constant encounters with death relate to the political and religious intrigues of his day. King Herod was a Roman ally, as were the Sadducees, the Hellenized Jewish elite whom Herod consulted in Matthew 2 and the core of the high priesthood. The gospel implies Herod and the Sadducees saw Jesus as a threat to their positions — if Jesus was King of the Jews, Herod was not. The Pharisees opposed Jesus' claims of divinity, which they considered blasphemy, and letting it go unchecked was a stain on them as teachers of Jewish Law.

What about the Romans? They are barely mentioned until the Passion narrative. Pontius Pilate likely had little interest in Jesus, and historians like Josephus and Philo both noted Pilate hated Jews (and vice-versa). As a pagan, Pilate had little reason to order Jesus' death on religious grounds, as he cared little for internal Jewish squabbles. His priority was maintaining Roman rule in Judea. When it seemed like the crowd in Jerusalem would instigate a Passover riot or revolt at Jesus' trial, Pilate released Barabbas, an actual rebel against Rome, and had Jesus crucified instead.

He suffered the worst form of Roman execution

Crucifixion ranked among the worst ways to die in the Roman world, meant to inflict as much pain as possible while also humiliating the victim. The condemned was tied or nailed to a cross, and the punishment dealt maximum pain by forcing the condemned to pick his poison. Hanging the victim by the wrists or hands from the cross beam compressed the body downward, preventing him from breathing properly. He had to push himself up by his feet (also nailed) for air. But that action made the nails rub up on the bone. So in return for a breath, one got an excruciating dose of nerve pain. The victim died slowly by asphyxiation, alternating between these two physical tortures. For Jesus, who had been brutally beaten before the ordeal, the pain was probably even worse from his wounds rubbing against the wood.

This form of public execution was also meant to be a reputation killer, and was reserved for the worst and lowest types of people like slaves, criminals, and prisoners of war of whom the Romans wanted to make an example. The plaque above the condemned's head stated the crime.

Those condemned by crucifixion could live for days, although merciful executioners might break the victims' legs or kill them after a few hours. In John 19:32-33, Roman soldiers break the thieves' legs so they can be buried before the Sabbath. Jesus, however, is already dead, and is spared the indignity.

His mother witnessed his crucifixion

The Eleusa icon, a style of Eastern Christian (particularly Eastern Orthodox) Marian representation, shows the child Jesus cheek-to-cheek with the Virgin Mary, sometimes with his arms thrown around her neck in a tender mother-child embrace. The style captures Mary's love for her only child, whom she saw die in agony.

There are differences between the Gospels regarding Mary at the Crucifixion, but they are all pretty thin on details (if they mention her at all). The Gospel of Mark simply says she watched it from afar, while the other two synoptica omit her completely. John places her at the foot of the Cross, wherein Jesus entrusts her to the evangelist. Perhaps the details of her suffering are unnecessary, as any mother would have suffered horribly to see a child undergo crucifixion. But just mentioning Mary's presence allowed readers to get that, as evidenced by centuries of Catholic art showing her weeping in despair.

While watching her son die was no doubt tragic, there is a theological explanation behind it, at least in Catholicism and Orthodoxy. Both denominations stress suffering as the source of new life. In watching Jesus suffer, Catholicism teaches Mary shared in his pain — pain that she did not suffer when giving birth to Jesus.

He survived two stoning attempts

First-century Judaism was littered with religious and ethnic divisions that Jesus had to navigate throughout his ministry. Chief among his rivals were the Pharisees, one of several first-century Jewish theological factions primarily focused on living out Mosaic Law. They viewed equality with God as blasphemy — a stonable offense according to Leviticus. So when Jesus declared in John 8:58, "Amen, amen, I say to you, before Abraham came to be, I AM," they tried to stone him. The crime? Using the divine name of God, YHWH, to describe himself. Ditto for the stoning attempt in John 10:38, where he claimed to be one with God the Father.

Despite some Pharisees' attempts to kill Jesus by this painful method, which involved burying the victim up to the neck and throwing rocks at his head, the two camps were not always implacable enemies. Jesus respected them as teachers of the Law and exhorted people to obey their teaching in Matthew 22:2-3. He was not above dining with Pharisees, nor did all Pharisees hate him — some warned him about King Herod's plot to kill him. Pharisee and Sanhedrin member Joseph of Arimathea gave Jesus a dignified burial, while many Pharisees followed him. Jesus simply held Pharisees to a higher standard and called out their members who failed to live up to it.

He had to flee his homeland as a child

Jesus made enemies immediately at birth, and foremost among them was King Herod of Judea, a ruler with his own epic backstory. Matthew recounts that Herod asked the magi – three Zoroastrian priests who traveled from the East to see Jesus — where the child was so he could adore him too. What Herod really wanted to do was kill him, but missed his chance because the Magi never returned. In response, he unleashed a horrible vengeance upon the children of Judea. According to Matthew 2:16, "When Herod realized that he had been deceived by the magi, he became furious. He ordered the massacre of all the boys in Bethlehem and its vicinity two years old and under ..."

While Herod's bloody work progressed in Judea, the Holy Family fled to Egypt. Coptic tradition holds they were generally well-received, sojourning for a few months at a time in a handful of towns from the Nile Delta all the way to Cairo. The last six months were spent living in a cave called Qussqam, and the Monastery of Al Muharraq commemorates that site today. Copts believe baby Jesus even left them a souvenir of his footprint on a piece of stone, which can still be seen today.

Once Herod died, the family was able to return home, but opted to lay low by settling in the Galilean town of Nazareth in what is today Northern Israel, rather than near Jerusalem, where Herod's successors could more easily find them.

His closest disciple abandoned him

Jesus certainly suffered betrayal from St. Peter, his closest apostle and the tough-talking chief of the 12 disciples. In the Garden of Gethsemane, Peter told Jesus in Matthew 26:35, "Even though I should have to die with you, I will not deny you." Approximately 40 verses later, Peter's resolve crumbled as he denied Jesus thrice, even denying knowing him, whether out of fear, doubt, or the circumstances of the tense moment.

Christ's reaction is all in the subtext, much of which is lost in translation. Luke 22:61 says that after the third denial, "the Lord turned and looked at Peter" — a reaction of stone-cold silence. Peter's triple denial of Jesus, including claiming not to "know" him in the Hebrew context, was a rejection of Christ. The expression Peter used does not mean they simply shook hands — it was the equivalent of saying someone was dead to you. It is the same expression Jesus used in Matthew 7:23 — "I never knew you," in reference to God's rejection of the wicked. In Hebrew and Aramaic, repeating things three times was a way of making it superlative, meaning a complete, total, no-holds-barred rejection, and was tantamount to rejecting God.

Most of the other apostles cut and ran

The Bible emphasizes Peter and Judas' betrayals due to their enormity, almost equating the two. But the other apostles did not do much better. Following Jesus' arrest, Matthew 25:56 simply says, "all the disciples left him and fled" — short, sweet, and searingly to the point. According to Catholic tradition, when Jesus was condemned to die, only St. John the Evangelist ("the most beloved disciple" of John 19:26-27) actually bothered to show up to the Crucifixion, comforting the Virgin Mary as she watched Jesus die. The rest, despite their stated fidelity to Jesus, were nowhere to be found.

The Bible is silent on what these disciples were doing. The crowd had attempted to arrest St. Peter alongside Jesus, after which the disciples fled, so the simplest explanation is that they were in hiding. They may also have felt ashamed about showing their faces before the dying Jesus at Golgotha, after their refusal to stand by him during his arrest.

In a final twist, given what happened to the bodies of the apostles, those who fled paid their dues in suffering later on. The absent 10 (excluding Judas) all suffered incredibly violent and painful deaths. St. John, on the other hand, is said to have enjoyed a long life — nearly a century old, by some traditions.

The Apostles were still unconvinced after the Resurrection

Imagine this: In Luke 18:34, Jesus openly tells his disciples he is God in the flesh and that he will die at the hands of the Gentiles and rise again. He dies the most excruciating death possible for their sin, yet all but one don't bother to show up. He is resurrected and runs into the apostles. Surely, that would have been enough, right? Here's what Mark 16:14 had to say instead: "[But] later, as the eleven were at table, he appeared to them and rebuked them for their unbelief and hardness of heart because they had not believed those who saw him after he had been raised."

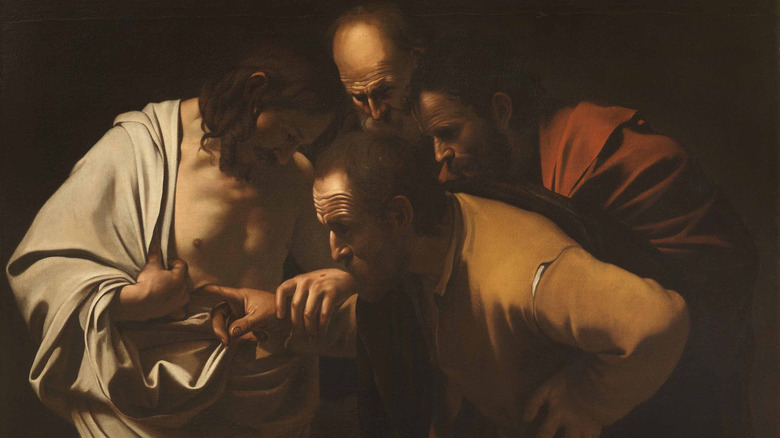

The Gospel of John gives specifics, honing in on the Apostle Thomas' conduct. In John 20:25, Thomas tells the other apostles, "Unless I see the mark of the nails in his hands and put my finger into the nailmarks and put my hand into his side, I will not believe" – never mind that Jesus was standing right in front of him. In this case, however, Jesus' reaction to his apostles' intransigence post-Resurrection is clearly stated.

Instead of getting angry before yet another denial, Jesus lets Thomas feel the wounds, along with a rebuke, "Blessed are those who have not seen and have believed" (John 20:29). Jesus' reaction is most illustrative of the Christian cliche that tragedy and doubt are teaching moments for strengthening faith — even for those who repeatedly fall along the way.