The Hidden Truth Of The Oregon Trail

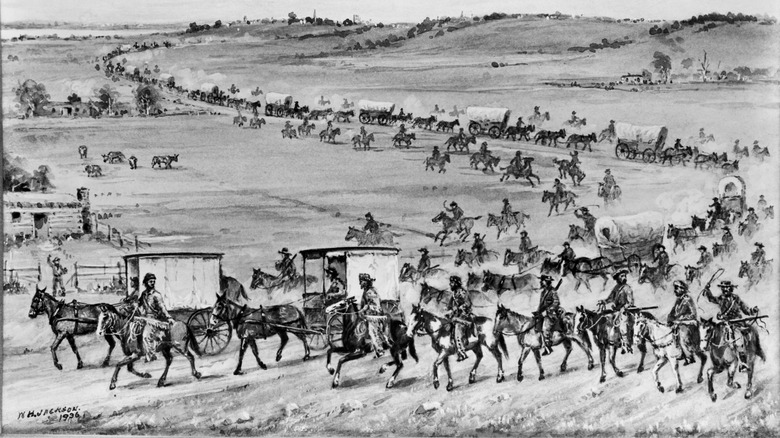

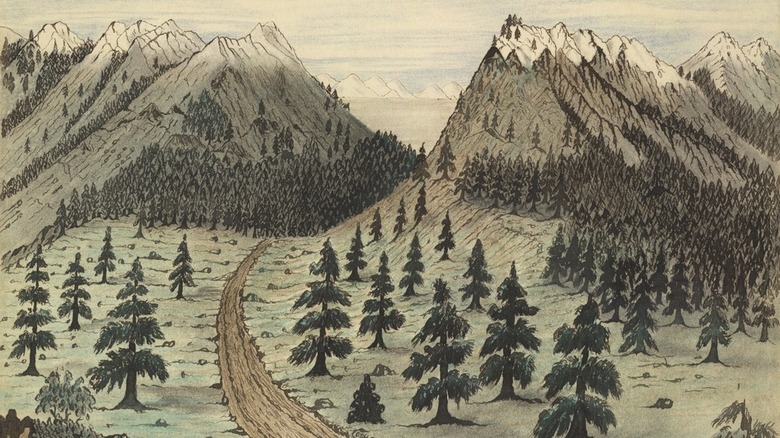

When it comes to American mythos, few names gleam with such a great glorified glow like these two simple words: "Oregon Trail." During the mid to late 19th century, the historic path, which stretched over 2,000 miles between Independence, Missouri, and Oregon City, offered those willing to make the arduous trek a chance to start a fresh new chapter in their lives. This was the alluring opportunity so many had been waiting for. Gold in California, "free" land in Oregon, the chance to escape the political upheavals and economic recessions plaguing the East ... the prospects that westward travel offered were endless.

Centuries later, it's easy to see how the Oregon Trail has become such a romanticized point of American history. Hollywood's incessant off-the-mark depictions of the Old West over the years have not painted the most accurate pictures of the time period, and that iconic "The Oregon Trail" video game wasn't exactly a stellar teacher, either.

Overall, yes, the Oregon Trail symbolized a transformative time of American history. But when it comes to the actual 2,000-mile trek itself, there are some hidden truths that need to be addressed.

The Oregon Trail was a piece of a larger puzzle

Just because a family was traversing the Oregon Trail didn't necessarily mean their final destination was Oregon. Those journeying west had several prime locations in mind. After all, California was supposedly flooding with gold; by 1848, thousands of Americans were hoping to score their shot at ultimate wealth by heading toward the soon-to-be state. Settlers heading to California would follow the Oregon Trail only until they reached Idaho. From there, they'd be forced to contend with Nevada's scorching deserts and challenging mountains.

A great number of Mormon travelers seeking refuge from religious persecution also made use of the Oregon Trail, but only after they reached Fort Laramie, Wyoming. Mormon pioneers often preferred staying north of the Platte River in an effort to avoid competition and confrontations with non-Mormon travelers. From Fort Laramie, they'd embark on the Oregon Trail for nearly 400 miles, before heading into the final stretch of their journey: 116 miles of terrible mountainous terrain that ultimately led to Utah.

Overall, the Oregon, California, and Mormon Trails (among others) were part of a larger emigrant network that joined together to create multiple "manageable" routes out westward. It wasn't all about Oregon!

The Oregon Trail was not as battle-ridden as some believe

When thinking of the Oregon Trail, it might be easy to imagine a bloody period where wandering travelers were locked in a never-ending cycle of hellish conflict with any Native American tribe they came across. Yes, gruesome encounters such as the Utter-Van Ornum Party Massacre (which took the lives of 25 settlers) did occur, but historical accounts show that fighting between the two groups was more of the exception than the rule. In fact, on the Oregon Trail, travelers and Native Americans were more often likely to engage in trade than they were to raise arms against one another.

During the early days of the Oregon Trail, when settlers first began making the move toward the Pacific Northwest, Native American tribes more or less left wagon trains alone. While hostilities escalated after the outbreak of the Civil War, statistics don't tell a story of insistent violence. Between 1840-1860, Native American tribes likely killed around 362 emigrants, while the settlers trekking the Oregon Trail killed about 426 Indigenous people.

Statistically speaking, the thousands wandering westward on the Oregon Trail had much graver threats to worry about than a random raid from a nearby Indigenous tribe. For decades, the worst type of foes that would plague emigrants on the trail were the invisible kind.

Disease was one of the most persistent threats on the Oregon Trail

It may be a meme now, but rest assured, dysentery was anything but to the emigrants making the journey west. The Oregon Trail was riddled with terrible diseases that plagued travelers at every turn; settlers had to worry about an endless column of merciless illnesses. Measles, influenza, scurvy, tuberculosis, pneumonia, smallpox, cholera (which proved to be the most fatal disease on the Oregon Trail), and yes, dysentery, all stalked emigrants relentlessly as they crossed the 2,000-mile stretch westward.

On the trail, the combination of terrible sanitary conditions, general exhaustion, and a lack of adequate drinking water created the perfect environment for these diseases to thrive. The National Park Service estimates that disease likely killed around 30,000 settlers traveling the Oregon Trail. On top of all of this, the "medicine" available to pioneers was, well, more aligned with treating symptoms rather than causes, to say the least. Whiskey, rum, vinegar, castor and peppermint oils, turpentine, and good ole doses of opium were some of the remedies emigrants had to look forward to, had they found themselves locked in a fateful and bloody battle with diseases like dysentery and cholera.

Wagon crushings and other fatal accidents were terrifyingly common on the Oregon Trail

As if rampant deadly diseases weren't enough to worry about, pioneers on the Oregon Trail also had to watch out for a wide range of fatal accidents eagerly waiting to befall them. Fatigue from long stretches of travel and general negligence led to many avoidable deaths. For starters, being killed by a sudden and unintended gun discharge was not exactly an uncommon occurrence on the Oregon Trail. A firearm in the wrong hands could prove just as fatal as disease for those joining a wagon train. Drowning while attempting a rough river crossing was also all too real of a possibility.

Another terrifyingly common way to die was being crushed by a moving wagon, and this was especially true for children. Certain historical accounts cite tragic instances where a child's injured and infected limb had to be amputated, without the use of any general anesthetic, only for the child to not survive the ordeal.

From suffering a fatal fall down a rocky slope, to children being crushed by wagons or mistakenly drinking the entire vial of their parent's opium "medicine," the number of records recounting travelers meeting terrible and accidental ends while journeying westward is simply staggering.

Enslavement and racism was alive and well on the Oregon Trail

Beginning from 1841, at least 300,000 settlers journeyed across the Oregon Trail. While the white pioneers making the trek westward were allowed to be empowered by the growing belief of Manifest Destiny — the philosophy rooted in the conviction that continental expansionism was an American right ordained by God — such optimism was in spite of Native Americans, and was certainly not meant to be felt by Black pioneers, free or otherwise.

Enslaved people, whether they wished to or not, had to follow the families they served across the Oregon Trail. Both free and enslaved African Americans had a nightmarish conundrum awaiting them in the territory. In 1844, Oregon had outlawed enslavement, giving enslavers three years to free their enslaved people, while also enacting a series of laws that made it illegal for Black people to live in Oregon. Five years later, this meant enslaved people like Rose Jackson, who had begged her owners to let her join them in their move to the territory, had to complete the majority of the journey across the Oregon Trail in a box covered with air holes.

George Washington Bush, a free African American from Missouri and a veteran of the War of 1812, traveled the Oregon Trail alongside his Irish wife and five children in 1844 only to find once they arrived that there was a new brutish law in place — the "Lash Law," any Black person who remained in Oregon would receive at least 20 lashings. This caused Bush to lead his party north of the Columbia River, where he'd find his own land to settle, all in spite of the legal injustices swarming around him.

The Oregon Trail birthed its own strange economy

With countless emigrants packing countless pounds and traveling for thousands of miles, it's only natural that the Oregon Trail led to the creation of its own bizarre economy. To put things into perspective, the average family trekking out west likely carried with them between 200-600lbs of flour, 150-400lbs of bacon, ample amounts of sugar, lard, and coffee, along with a broad assortment of other necessities.

Frontier towns like Independence, Missouri and Council Bluffs, Iowa had an absolute field day with pioneer families. Rival towns would employ messengers to travel East to literally talk trash about one another — all in an attempt to make sure their town gained the most traffic. Once settlers were in a frontier town, the merchants pounced, convincing families they needed everything and anything.

Some things never change; just as today, when one might overpack for a weekend road trip, settlers in the 1800s often overestimated just how much they'd need or how much their animals and wagons could haul. The solution? Start tossing items out. This turned out to be a goldmine for prowling scavengers; all one needed to do was wait for a wagon train to leave a starting point like Independence and soon follow. They'd likely be met with a cast iron stove or barrels of food. Dumping provisions was simply a tragic recurring theme on the Oregon Trail. Wherever a wagon train went, it'd nearly always leave a trail of discarded supplies and goods.

The Oregon Trail helped create a market for terrible trail guides

In 2024, making a wrong turn or missing an exit is irritating — in 1800s America, when trekking westward, going the wrong way could be a death sentence. And, unfortunately for 19th-century pioneers, they had a wide selection of "guidebooks" anxiously waiting to give them misleading directions.

American expansion out west meant there was money to be made in the trail guide market. In early 1848, as soon as folks began hearing all that talk of gold in California, heaps and heaps of guides began being printed at a rapid rate. And, of course, most of them were terrible. They eagerly gave flowery prose when it came to descriptions of their potential destinations, but in terms of legitimate directions on how to actually get there, they'd either offer nothing or plain inaccuracies.

For example, pioneers would read that there'd be no water in one area, only to find a fresh spring once they arrived. Such erroneous advice culminated in the tragedy of the Donner Party, an expedition that followed the unreliable writings of Lansford Hastings, the author of "The Emigrants' Guide to Oregon and California," and ended with death and cannibalism.

Most people had to walk, not ride, on the Oregon Trail

Oregon Trail symbolism automatically conjures up images of hearty animals and sturdy wagons plodding along endless meadows, dirt roads, and rocky mountain terrain; rightfully so, too, as both served as indispensable tools for an emigrant's journey out west. However, this doesn't mean that most travelers had the luxury of hopping onto the wagon or atop a horse whenever they felt like it. No, the main mode of locomotion for a great many on the Oregon Trail, especially children, was walking– endless, endless walking.

This meant a family's wagon could be packed with as much as possible. A ride inside the wagon wouldn't have exactly been a delight anyways; the paths out west weren't paved with any fancy network of roads and with no suspension system, being crammed inside a crate on wheels sounds like a wobbly nightmare.

Overall, a good day for a wagon train was when it completed at least 18 miles. Taking into account how the day for emigrants on the Oregon Trail started around four in the morning and ended around five in the evening, this meant several hours of walking every day in unpredictable terrain, while likely wearing less than adequate footwear. For 2,000 miles and for several months, this is what an emigrant had to look forward to on the Oregon Trail. Walking, walking, walking. Sprinkle in some dysentery on top of this hardship sundae, along with a party member suffering from an accidental gunshot wound, and you have yourself a terrible, terrible time.

On the Oregon Trail, women were expected to pull double duty

The 19th century wasn't a time when married women were making decisions about their household's future; if their husband wished to uproot their family's life and make the 2,000 mile trek across the Oregon Trail, then that was the end of it. As Margaret Hereford Wilson wrote to her mother in 1850: "I am going with him, as there is no other alternative."

On the trail itself, a woman's life was strenuous just like everyone else's, but maybe doubly so due to the work expected of them. Not only was it her duty to prepare the day's meals, often with limited supplies, if her husband or other men in the wagon train fell ill, then they'd also have to step up for guard duty. It also wasn't a rarity for women to partake in other "manly" jobs, such as herding the livestock and driving the wagon. Men, even on the Oregon Trail, were much more likely to be apprehensive and mindful about accidentally performing any task that was traditionally reserved for women.

Indeed, the mere act of a husband fetching water for the day's laundry could garner camp attention. As one rather hilarious (and sad) account reads: "When the first Saturday came round, I prepared to do some of my family laundry work. My husband ... carried water ... filled the washboiler and placed it over the open fire for me. Mrs. Norton was a deeply interested spectator ... and remarked rather sadly, 'The Yankee men are so good to their wives, they help 'em so much'" (per End of the Oregon Trail Interpretive Center).

From tending to camp to caring for children to performing any and every task asked of them, women on the Oregon Trail were the ultimate unsung heroes.

No, the Conestoga wagon was not that widely used on the Oregon Trail

If you ask someone to describe the first image they think of when you say "Oregon Trail," an image of a massive wagon is probably going to appear in their minds, specifically, the enormous Conestoga wagon. Over the years, the vehicle has become synonymous with the rugged pioneer spirit that symbolized the era of American expansionism out west.

Ironically, the Conestoga wagon was not actually used that often by emigrants traveling the Oregon Trail; it was far too heavy and more often relied upon by people living in the eastern United States. The wagon was 26 feet long, 11 inches wide, weighed between 3000 and 3,500 pounds unloaded, and usually required over five horses to properly pull. Even the strongest of oxen could die pulling the Conestoga wagon for too long. On top of this, the wagon fared the best when it was trudging along decent enough roads. The unpredictable and bumpy patterns of natural terrain, such as that found in the Great Plains, simply spelled disaster for something so heavy.

If any piece of equipment should be the Oregon Trail's poster child, it's the Prairie Schooner. Weighing around 1,300 pounds unloaded, this wagon was more or less half the size of the Conestoga and was a much easier haul for a group of four to six oxen, or six to ten mules. The Prairie Schooner also boasted a pair of smaller front wheels, which gave the driver some leeway for sharper turns, and it could be taken apart for repairs. Overall, when it came to uplifting one's entire existence and picking that special wagon to take out West, the Prairie Schooner was the best — and only — choice.

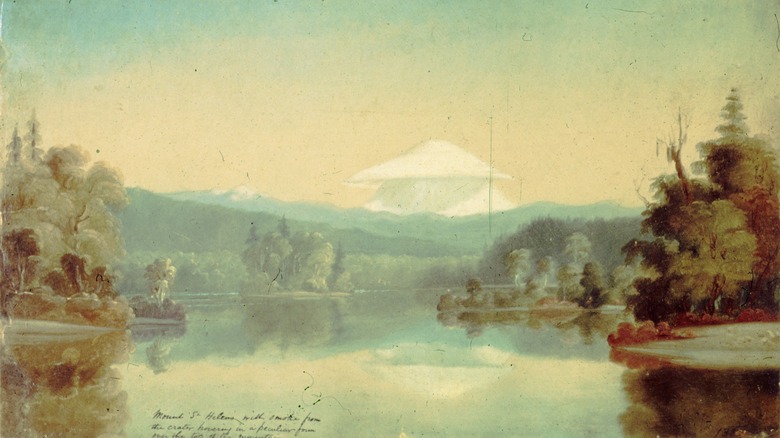

The rise of railroads made the Oregon Trail obsolete

In May 1869, the United States of America, entering its brutal and ponderous Reconstruction Era as it attempted to deal with the many gaping wounds left opened up by the Civil War, saw one of its most significant infrastructural achievements completed: the First Transcontinental Railroad.

The first railway, brought to life by the perilous and unsung labor of 12,000 Chinese immigrants, linked Sacramento, California, with Omaha, Nebraska. For the first time in the nation's history, the West truly met the East. This colossal technological innovation helped the healing United States enter a new uncharted chapter in its history. And with more rail lines not far off, this meant saying a gradual goodbye to the Oregon Trail. In what originally may have taken pioneers six months, passengers could now arrive at their destination in mere days.

Emigrants trekking the trail with their wagon trains were still a common enough sight in the 1880s as not everyone could afford this new mode of travel. However, soon enough, the sight of endless columns of oxen-led wagon trains became a symbol of a bygone era, and an emblem forever etched in American legend.