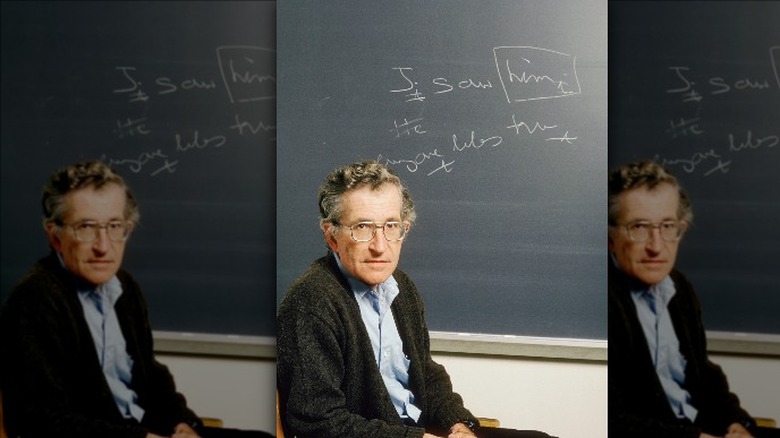

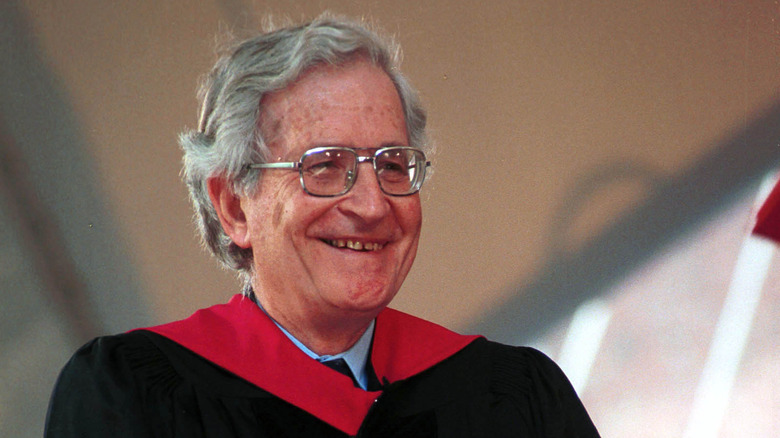

The Untold Truth Of Noam Chomsky

It is difficult to overstate the far-reaching influence of Noam Chomsky, a scholar and activist whose contributions across a range of fields have shaped disparate discourses — and built bridges between them — for seven decades. He first made his name as a disruptive new voice in the field of linguistics, then became a prominent scholar in both the humanities and science, before emerging as a political activist and dissenter willing to shine a light on totalitarianism and moral wrong with a piercing scientific logic.

As the twentieth century became the twenty-first, Chomsky's legacy as both an academic and a dissenter seemed assured. However, Chomsky, who was born in 1928 and who had his first academic article published in 1952, has seldom fallen silent, continuing instead to speak and publish to ensure he remains a relevant voice in the present decade.

Meanwhile, Chomsky's critics have remained numerous, and their arguments against him have multiplied as his sphere of influence has continued to grow. As such, he remains a controversial and divisive figure. Here are just some of the reasons why the name 'Chomsky' remains as potent today as it did in the early days of his career.

Why Chomsky writes in many fields

It is certainly true that Noam Chomsky's interests are wide-ranging, and that he has been singular in turning his intellect to a diverse number of subjects. According to "Noam Chomsky: A Life of Dissent," in his youth, Chomsky was uniquely placed to become a celebrated polymath.

Though he came from a comparatively humble background in Philadephia, both of his parents were educators. His father, William — a linguist and expert in Hebrew, who likely ignited in Noam his love of languages at an early age — was especially dedicated to helping to develop free thinking and a willingness to engage with the larger issues in society among his students, and educated his son to view the world with the same openness.

Similarly, Chomsky's mother, Elsie, was a teacher, but she was also an insightful and passionate activist of the political left, who laid the groundwork for Chomsky's political philosophy: As an in-demand public speaker, she may have instilled in the otherwise shy Chomsky both the feasibility and importance of public speaking as part of one's intellectual life.

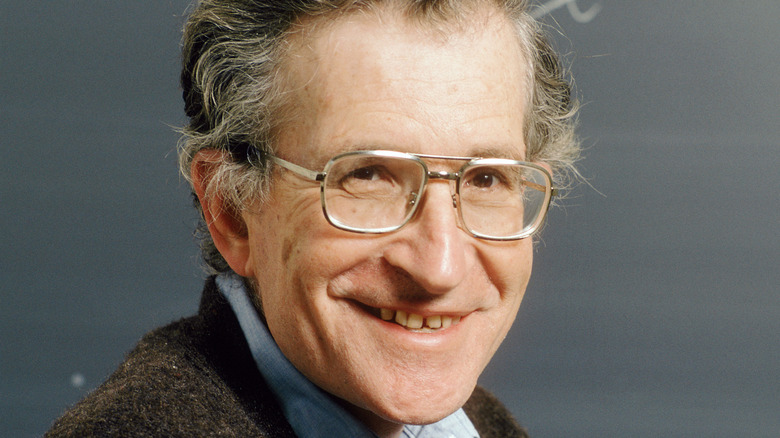

Chomsky thinks he's boring

Noam Chomsky is now considered one of the most influential writers and thinkers of modern times, drawing parallels with Jean-Paul Sartre and George Orwell. But while the latter examples became acclaimed personalities, Chomsky is reportedly opposed to his own fame, according to the eponymous "Noam Chomsky" by Wolfgang B. Sperlich. Rather than consider himself a celebrity or personality that the public ought to know, Chomsky instead paints his role as functional. He believes his job is to expose propaganda and promote the use of logic to see the world as it really is, to focus people's attention on the issues at hand, whereas his own life — that of a quiet but hardworking academic — is barely worth knowing at all.

According to "Noam Chomsky: A Life of Dissent," Chomsky said, "Things happen in the world because of the efforts of dedicated and courageous people whose names no one has heard, and who disappear from history. I can give talks and write because of their organizing efforts, to which I'm able to contribute in my own ways."

Similarly, Chomsky is said by his own biographer Robert F. Barsky to "deplore" biographies in general, preferring to judge ideas themselves rather than the personalities attached to them — a rule he applies to himself. According to a letter he sent to Barsky, Chomsky even refuses to revisit footage of himself, such as the acclaimed 1992 documentary about his work, "Manufacturing Dissent: Noam Chomsky and the Media," which Barsky directed.

Chomsky triggered an academic war

For many, Noam Chomsky's radicalism arises from his political activism, whereas his work in the literary field is dry and technical by comparison. But even his work in linguistics has been controversial, with his early work challenging the prevailing assumptions of the day within the field and sparking what was later known as the "linguistic wars."

As the critic Randy Allen Harris explored in his book "The Linguistics Wars," Chomsky first made a notable impact within linguistics with his 1957 monograph "Syntactic Structures," a work that catalyzed what Harris describes as a "revolution" in the field. The monograph was, at first, considered combinable with developments in linguistics from previous decades — most importantly the "Bloomfieldian superstructure" of linguistics that dominated the field during Chomsky's emergence.

But as Chomsky's ideas began to circulate, it became clear that the effect of his theories was becoming transformative, and dragged linguistics into a full-on logical investigation of syntax in a way that had never been attempted before. In doing so, Chomsky developed the theory of "universal grammar," which argues that the human ability to use language is innate, rather than a learned skill. According to Harris, Chomsky admits that his work eventually came to receive a great deal of antagonism from his own colleagues, because he framed his own work as an attack on what had come before.

Chomsky said America is an imperialist power

When hearing the word "empire," many think of ancient Rome, the British Empire, Persia, and historic Chinese dynasties. Not so many, perhaps, think of the United States, a federal republic and liberal democracy that proclaims to hold freedom in high regard.

But Noam Chomsky's formulation of the U.S. in his public discourse frames his native country as an imperialist power. While the official line in U.S. foreign policy typically states that, in conflicts such as Vietnam and Afghanistan, military intervention occurs for the sake of the freedom and safety of the U.S. and its allies, Chomsky's view is rather more cynical. As noted by his biographer Wolfgang B. Sperlich, Chomsky argues that U.S. foreign policy after World War II has been "designed to create and maintain an international order in which U.S.-based business can prosper, a world of 'open societies,' meaning societies that are open to profitable investment, to expansion of export markets and transfer of capital, and to exploitation of human and material recourses on the part of U.S. corporations and their local affiliates. 'Open societies,' in the true meaning of the term, are societies that are open to U.S. economic penetration and political control."

Chomsky first emerged as an anti-war figure in the 1960s, opposing U.S. intervention in Vietnam. But he has continued to be a vocal critic of what he calls the U.S.'s "imperial grand strategy," as discussed in his book "Hegemony of Survival: America's Quest for Global Dominance."

Chomsky was accused of being a holocaust denier

Though Europe has typically been more receptive to Noam Chomsky's views than his native U.S., it was in France that he experienced one of his most high-profile and, ultimately, damaging controversies, which became known as the 'Faurisson affair.'

Per Robert F. Barsky's "Noam Chomsky : A life of dissent," Robert Faurisson was a professor of literature at the University of Lyon, France, who in the 1970s published documents in which he questioned the truth of the Holocaust. As Chomsky would later put it (via The Nation), "he denies the existence of gas chambers or of a systematic plan to massacre the Jews and questions the authenticity of the Anne Frank diary, among other things." Faurisson's views led to his expulsion from the University of Lyon, who argued that his views meant he was likely a target for violence on campus, and to him being convicted of "falsification of history" — a crime in France.

Per Barsky, Chomsky was asked by a colleague to sign a petition asking for Faurisson to be protected and for his position to be reinstated. He agreed on the grounds that all views, even the most egregious, should be allowed freedom of speech. Chomsky was widely criticized for the move, and when an essay of his on the subject of freedom of speech was used — without his knowledge — as the foreword to a book of Faurisson's writings, he was accused of endorsing Holocaust denial himself. Chomsky has maintained that his defense of Faurisson does not extend to the content of his writings, and has never apologized for his position in the affair.

Chomsky was criticized for his stance on Cambodia

If the Faurisson affair and its association with Holocaust denial gave ammunition to Noam Chomsky's critics, who questioned his judgment over the affair (via The Nation), his ongoing criticism of U.S. foreign policy and conflicts overseas also ran into controversy. His remarks in the late 1970s regarding events then taking place in Cambodia had an especially negative effect on his reputation for decades after.

As reported by the ABC, Chomsky and his colleague Edward Herman were vilified for seemingly discounting the genocide committed in Cambodia by Pol Pot and his communist military group, the Khmer Rouge, the crimes of whom had been reported in several western publications as amounting to the massacre of some two million people (per Britannica). Though Chomsky and Herman had claimed they were only attempting to expose the lack of veracity attached to the figures circulating at the time, Chomsky found himself met with hostility during public appearances by those who claimed he was a supporter of Pol Pot, while even in the media he was labeled an apologist for the regime, according to the ABC.

He was defended passionately by Christopher Hitchens

After taking several controversial positions in the 1970s, Noam Chomsky was increasingly considered a divisive figure, with many publications beginning to characterize him as a formerly interesting radical who had gone off the boil. However, some public intellectuals thought that Chomsky was being unnecessarily pilloried, and sought to defend him in print. Among them was fellow Marxist Christopher Hitchens, the journalist and critic who would later find fame as the author of the atheist bestseller "God Is Not Great."

In a 1985 article titled "The Chorus and Cassandra: What Everyone Knows about Noam Chomsky," Hitchens makes clear his admiration for Chomsky, a lecture of whose he recalls having attended as an undergraduate student, but highlights how Chomsky's critics were sidelining their target baselessly. One example he held up as an unfair critic was Geoffrey Sampson, who argued that Chomsky had "forfeited authority as a political commentator," due to controversies such as his criticism of the discourse around events in Cambodia and the Faurisson affair,

Hitchens also took issue with characterizations of Chomsky that claimed he was an "enemy of the Jewish state," and chastised the western media for its hostility toward dissenting voices such as Chomsky's.

Chomsky is highly skeptical of the media

Noam Chomsky himself has long been a critic of the western media, which became one of his most discussed subjects from the 1980s onward.

Per Open Culture, in 1988, Chomsky co-authored with Edward Herman the book "Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media," which forwards the propaganda model of mass communication. It proposes that rather than hold governments to account, news outlets typically work to further the interests of the ruling class, while simultaneously reinforcing the illusion that liberal democracies are truly democratic — an assumption that Chomsky is profoundly skeptical of. The same source sketches how the propaganda model operates through five 'filters' to encourage citizens to accept the status quo.

Chomsky and Herman's ideas concerning mass media have been highly influential, while in recent years, academics such as Christian Fuchs have revisited Chomsky's work. They argue that, even in the twenty-first century, with the advent of the internet and mass communication, the model proposed in "Manufacturing Consent" remains highly relevant to how the contemporary media operates.

Chomsky has been banned more than once

In 2009, the British journalist Seumas Milne wrote an article in The Guardian in which he contacted Noam Chomsky, lamenting the lack of mainstream attention given to Chomsky's work by the American media, despite his evergreen relevance.

As Milne explains, in the twenty-first century Chomsky, then 82, still enjoyed a considerable following on the lecture circuit. At the same time, his many books typically sold hundreds of thousands of copies. Still, despite all this, Chomsky was invited to make very few television appearances, while his ideas were often dismissed. Milne suggests that Chomsky's 'relentless' dissidence, particularly against U.S. foreign policy, is undoubtedly the reason for his suppression, and points to the shocking fact that prisoners in Guantanamo Bay (pictured) have been banned from owning his books.

Rather than being past his prime, it seems that Chomsky and his ideas are as controversial and potent as ever. Via The Guardian, the year after Milne's interview, Chomsky was barred from entering the West Bank to give a series of lectures at Birzeit University and the Institute for Palestine Studies, as a result of his criticism of the Israeli occupation of the region.

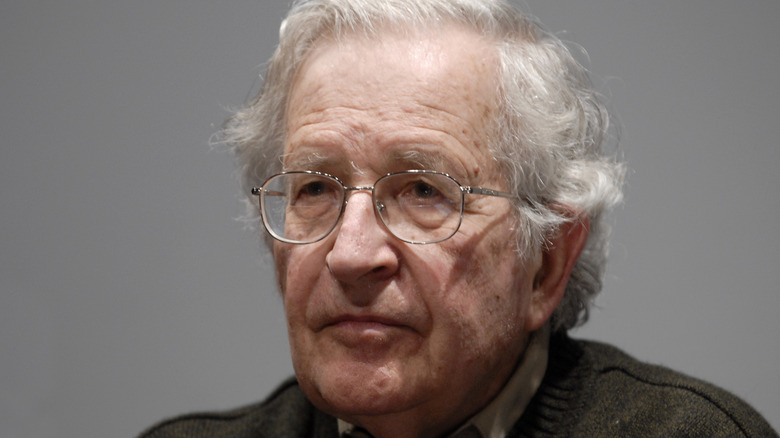

One of the most cited academics ever

Noam Chomsky has remained a controversial thinker outside of his primary field of linguistics ever since the publication of his essay "The Responsibility of Intellectuals." This was a clarion call to Chomsky's fellow academics to become politically active during the Vietnam War, the context of which he discussed half a century later in "The Responsibility of Intellectuals: Reflections by Noam Chomsky and Others after 50 years." But by transgressing the traditional boundary between institutional scholar and public intellectual — and encouraging others to do the same — Chomksy's achievements as an academic are perhaps at risk of being overlooked.

The proof of the potency of Chomsky's thought rests in his impact on academia, as his biographer Robert F. Barsky — who places Chomsky among the greatest minds to have ever lived, including Galileo, Mozart, and Picasso — makes clear in "Noam Chomsky : a life of dissent." Per Barsky, Chomsky was the most cited living person in the arts and humanities between 1980 and 1992. He has also achieved lasting impact in the sciences, with thousands of citations between 1974 and 1992, and he remains ranked among the world's most highly cited researchers.

Chomsky's ideas continue to be challenged

Though Noam Chomsky's ideas continue to circulate widely and he prospers as a public intellectual in the twenty-first century, Chomsky still has countless opponents, both within academia and in the wider world.

Meanwhile, even his most foundational work in linguistics is still up for debate. As reported in The Guardian, Chomsky's theory of universal grammar — through which he first came to prominence in his chosen field — is now questioned by other famous linguists such as Daniel Everett. In his 2012 book, "Language: The Cultural Tool," Everett argues that there is no evidence for universal grammar and that "[l]anguage is possible due to a number of cognitive and physical characteristics that are unique to humans but none of which that are unique to language."

Elsewhere, publications not on the political left, such as the conservative literary journal "The New Criterion," continue to accuse him of the intellectual mistake he was characterized as making regarding Cambodia's genocide in the 1970s, his criticism of U.S. foreign policy after the September 11 terror attacks, of "rationalizing" Al Qaeda and open anti-Americanism, and of supporting the authoritarianism of communist regimes.

Chomsky had unexpected praise for Donald Trump

It is a challenge to think of two public figures less similar than the intellectual Noam Chomsky and the businessman — and former president of the United States — Donald Trump. As one might expect, Chomsky had some choice words for the former president when he was in office.

In October 2020, The New Yorker journalist Isaac Chotiner interviewed Noam Chomsky, who had endorsed Joe Biden in that month's presidential election. Chomsky told Chotiner that he believed Trump to be "the worst criminal in human history," lambasting the president for his denial of climate change science, and his administration's withdrawal from the historic Paris Agreement to cut carbon dioxide emissions.

But in May 2022, as war between Russia and Ukraine continued to develop, Chomsky raised eyebrows — and once again attracted criticism — when he unexpectedly praised Trump for his stance that the west should "[m]ove toward negotiations and diplomacy instead of escalating the war," as Chomsky described it (via The Print). This, in his opinion, set him apart from other western leaders, whom Chomsky believed were not making enough of a commitment to end the conflict as soon as possible.